10 boxes your digital activism must tick

A good campaign is not about your audience passively receiving your message. It’s about interaction, engagement, connection. Here are 10 key success factors to make this happen.

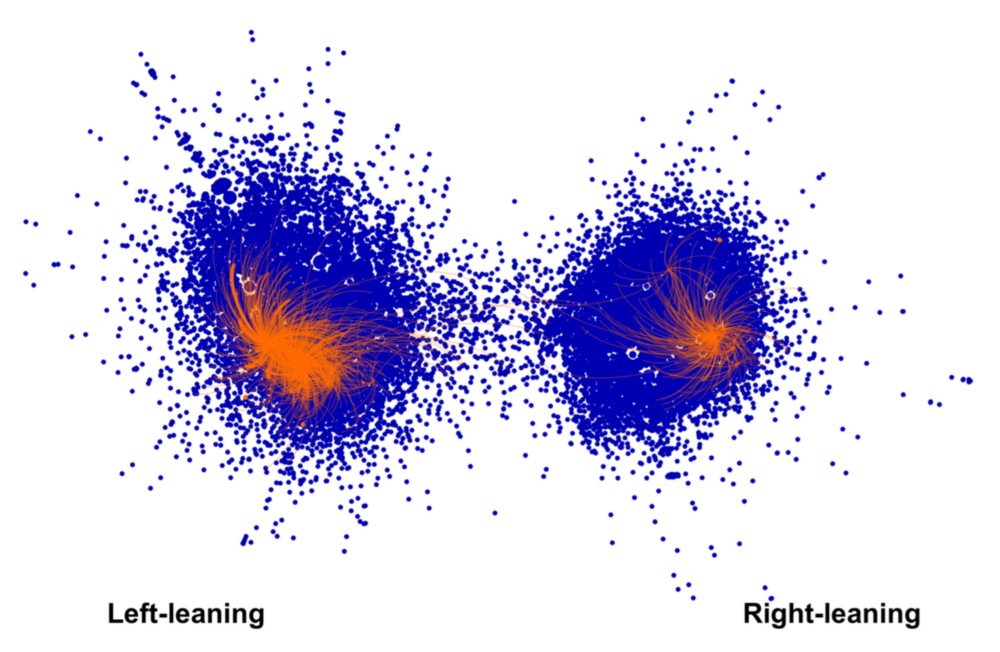

1.Go where your target is. It can never be repeated often enough: engagement happens best where users already are, as opposed to where the campaign is. Hence, the golden rule is to spend 30% of the time on the campaigns’ media and 70% on the media/spaces that the audience already uses. For how this worked with using make-up influencers to increase engagement see this article

2. Make it relatable. People might care for your issue but not enough to take action, unless you frame it in a way that makes them realise the mobilisation is also towards their own interests and motivations. So talk to people’s interests before talking about yours. And it’s best to not assume you know what triggers your audience. A bit of research into this is always a good idea.

3. Make it as easy as possible while still making it meaningful (people are not naive enough to believe they will solve a big problem with a simple click, so infantilizing them is not recommended). Everybody has heard of “slacktivism” or “clicktivism”)

4. Make it innovative. There is lot of digital campaigning going on, so your audience beyond your faithful followers is unlikely to participate in your campaign unless you make it attractive enough, especially if you expect people to share.

5. Make people feel good about their actions. People need rewards. This can be gratitude, visibility of results, etc. For people who strongly focus on recognition, easy tools like leaderboards might be effective

6. Create a community of action. A great example was the “Home to Vote” campaign for the Irish referendum on marriage equality: people who flew back home just so they could vote on the referendum posted images of themselves travelling back and shared pics with #hometovote, which made them part of a small community of “hardcore” supporters. More info HERE

7. Follow up and build on people’s engagement: Keeping people informed of the results of their specific participation is better than sending them « standard » newsletter info. New calls for action should reference and pay tribute to past engagement: it is so annoying when you have participated in several actions and still receive messages as if you had just joined.

8. Make it real. A SMART objective is winnable, targeted, concrete.

9. Enable people. Audiences which are already regularly engaging with your cause don’t appreciate being commanded. They consider themselves committed enough to take a meaningful decision on their involvement. They might appreciate being consulted on new ideas, being invited to webinars, etc.

10. Give people control over what type of information they will receive. This will make this information more impactful as users consider it as a response to their request and therefore take better ownership. This control can take easy forms such as pre-formatted questions (e.g. “what does my religion (really) say of same-sex relationships?)

RESOURCES FOR CAMPAIGNERS

Specific engagement strategies on INSTAGRAM

How to find your audiences where they already are (instead of just hoping they will come to you): an example of how to talk to online gamers about toxic masculinity while they play

How to use unusual influencers to reach your target audience: make-up vloggers become activists

And some resources in general about digital campaigning:

For example this article about what makes people share your content (or not)