Is It Time to Retire the Word ‘Privileged?’

This article by Lewis Oakley first appeared in The Advocate

———-

As an equality activist, it’s my job to keep track of the tools that effectively change hearts and minds — hitting the delete button on tactics that worked five years ago and keeping my eye on new and inventive ways to get others to empathize and understand.

If understanding is indeed the goal, the word “privilege” is no longer having the desired impact. And that’s giving it the benefit of the doubt that it ever did. It may be a good word for people to let out their frustrations, but if we’re serious about change it’s time to leave the word in the past.

As someone who studied linguistics at university, I understand how loaded this word has become. Whether intentionally or not, it implies the person you are talking about is somehow responsible for their difference. It’s calling them guilty.

The word immediately puts a person’s shields up. So much so that they actually won’t hear your point, they are too busy thinking of defenses.

As a bisexual activist, I rarely call someone biphobic. I may say that a certain thing they said was biphobic, but I know writing an entire person off as phobic isn’t going to help. No one has ever agreed to change their behavior because someone called them a name.

When I encounter negative perceptions of bisexuality, the first thing I do is ask questions. If you’re going to change someone’s perception, you need to know how their brain works. “So why do you think bisexuals will never be satisfied in a relationship?” “Okay, but surely you’ve been attracted to other women that aren’t your wife?” “Are you not satisfied?” “Then why wouldn’t I be?” The skill of an activist is to use someone’s own logic to prove the point.

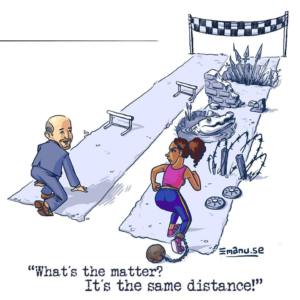

Some may argue that a lot of people have accepted that they have privilege, and are fine recognizing it. This is true, and part of the battle is won with these people. However, the truth is, for many people, while they have privilege in certain ways, they don’t see themselves that way. They see themselves as a whole person; it’s labeling someone in a way they don’t recognize. It makes you wrong in their eyes before you’ve got to the point you’re trying to make. Some may also feel that you lack empathy; you might see them as privileged because they are straight or white, while they see themselves as severely damaged from their father’s suicide, for example.

Just a slight change in the wording can dramatically change responses and perceptions and encourage people to empathize; think of words like “lucky” or “blessed.”

Rather than exclaiming, “As a straight person you’re privileged,” try explaining “You’re lucky that you can walk down the street holding your partner’s hand and not worry about being attacked.”

For some reason, we’ve reached a point in history where we think shouting and name-calling will produce equality. When in truth, it’s just going to raise the temperature.

The next time you go to use the word “privileged,” ask yourself, Will this make someone understand the plight of the marginalized? Will this word have the desired outcome of changing hearts and minds?

Lewis Oakley is a U.K.-based bisexual activist. Find out more about his work at lewisoakley.com.