How to use AI-Assisted mass focus groups

This article was written with items taken from Loopanel

AI is transforming the way we conduct focus groups, making the process faster, more efficient, and more insightful. From generating AI focus group questions to analysing transcripts and drafting reports, AI focus group tools are helping researchers at every stage of the process.

The research challenge

Anyone who has conducted social research will have faced these challenges:

- Focus groups are too small to be really representative of the targeted demographic

- Residential focus groups processes generate a lot of social biases, which can predict what people generally say on an issue, but not necessarily how they feel. These focus groups can be useful to determine messages that play into social conformity, but fail to give insights into other, e.g. values-based, approaches

- Residential focus groups are difficult to organise, expensive and time-consuming

Recently developed AI-assisted tools can provide alternative or complementary methods, well worth exploring.

How does it work?

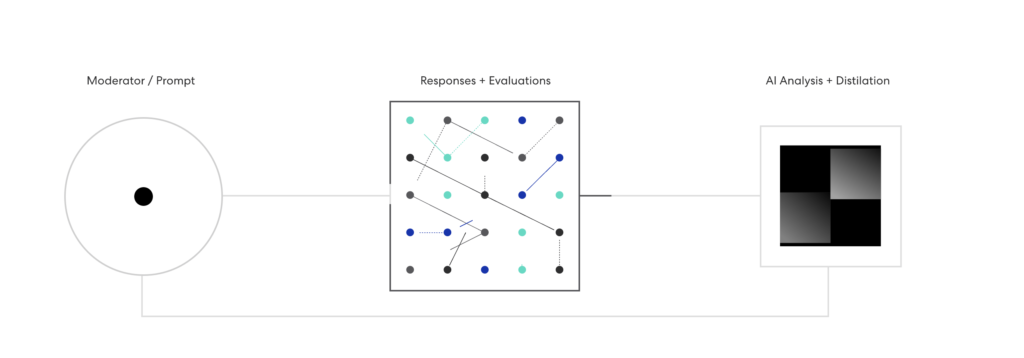

- A question is being asked on a specific App platform to a range of participants (provided by the app randomly, sampled by the provider, or brought by the client)

- Participants respond in their own words. Using free-form text, they can share their honest thoughts without constraints, giving you access to a rich source of data that supports your hypothesis — or takes you down an unexpected path you hadn’t considered.

- Participants evaluate responses shared by others. This helps understand how well responses reflect the views of specific segments and discover areas of resonance.

- Each response is immediately analysed to understand its meaning and how similar or different it is from other responses. This predicts how participants would vote on every response they didn’t see (since voting on thousands of responses would be impossible).

- Results are generated instantly, organised and analysed by themes, codes, sentiment, etc

Benefits:

One of the most significant benefits of AI in focus groups is its ability to streamline time-consuming tasks. AI-powered tools can assist researchers in creating questionnaires, transcribing audio recordings, and generating reports.

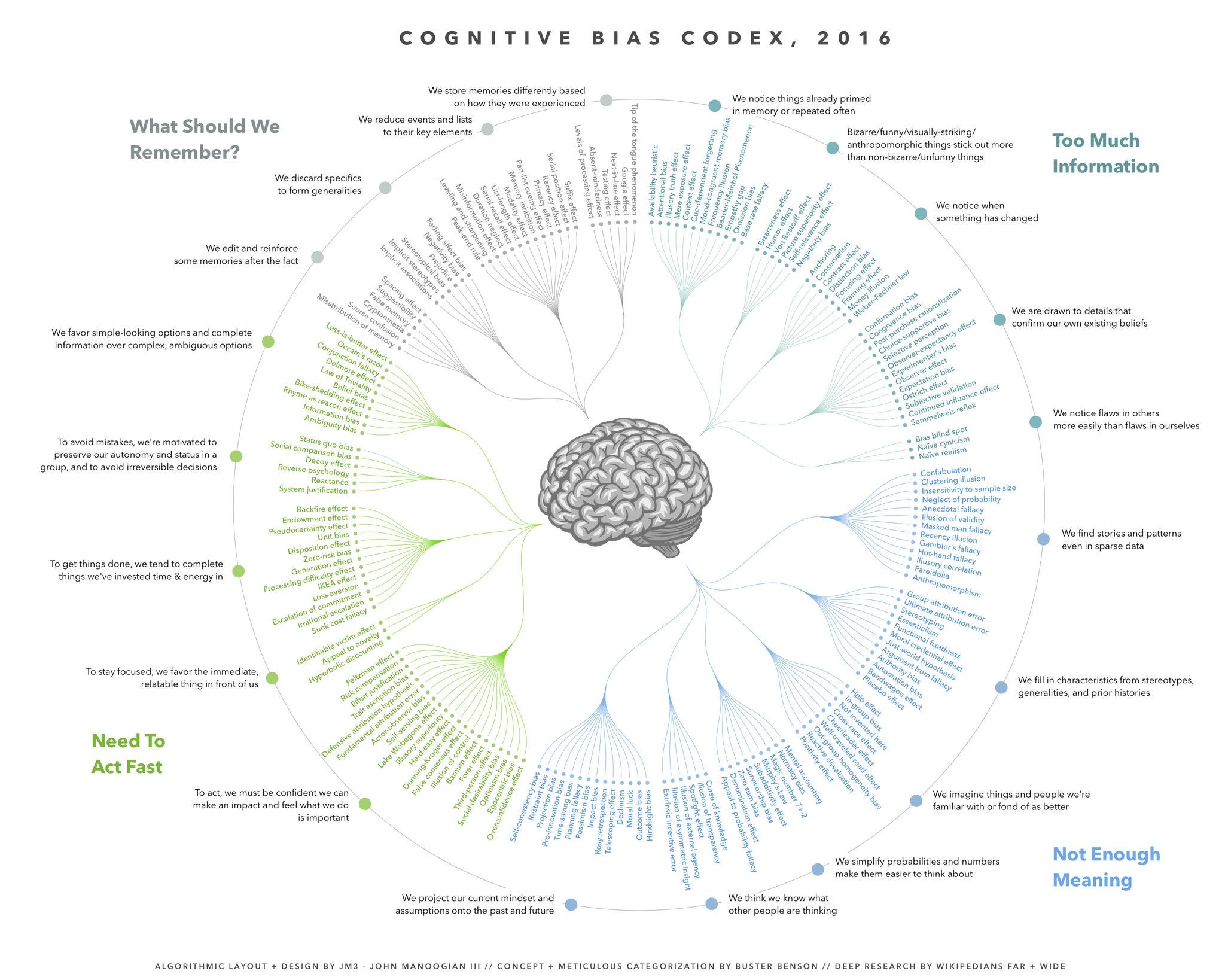

Also, AI algorithms excel at identifying patterns, sentiment, and key themes within large volumes of qualitative data, so AI can help researchers quickly identify trends and connections across multiple focus groups, enabling them to draw more comprehensive conclusions.

One of the biggest challenges of focus groups is the amount of data you’re dealing with. If you’re running multiple focus groups, you may end up with 100s of pages of transcripts, notes, and observations. While we as people find this volume of data extremely overwhelming, AI can help categorise it for us to make it easier to consume, process, and review.

Challenges:

However useful it can be, it’s important to remember that AI is not a replacement for human expertise and judgement. While AI can provide valuable assistance, researchers must still use their skills and knowledge to design effective focus group studies, interpret the results, and make informed decisions. As with any new technology, it’s crucial to understand the limitations and potential drawbacks of AI in focus groups, such as the risk of biased or inaccurate outputs. This risk is the result of AI algorithms being developed from data provided by a mainly white Western audience.

Furthermore, AI will not be able to identify determinant cues such as facial expressions, or nuances such as humour, sarcasm, etc.

Using AI in focus groups involves collecting and analysing large amounts of personal data. This raises important concerns about privacy and data security. Researchers must be transparent about how they’re using AI and ensure they have robust measures in place to protect participants’ personal information. For example, be very careful if you’re using open chatbots like ChatGPT to analyse data—make sure you’ve opted out of letting them use your data for training purposes.

Providers:

A useful list of tools, with their respective qualities, is available HERE.

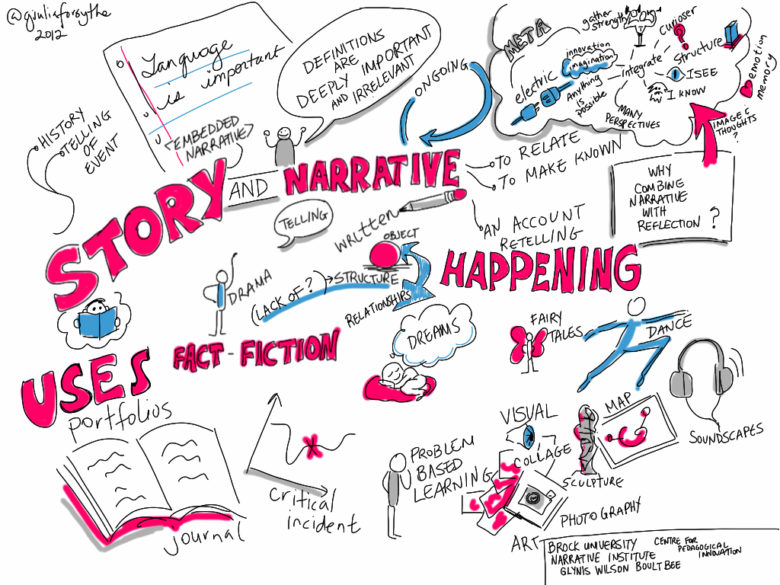

Like many of us, you might be facing attacks from opponents consisting of lies, propaganda, and other forms of disinformation.

Like many of us, you might be facing attacks from opponents consisting of lies, propaganda, and other forms of disinformation.

Social service organisations collectively spend millions of dollars each year on communications that focus on informing people. Sadly, these kinds of efforts ignore the scientific principles of what motivates engagement, belief, and behavior change. Consequently, a lot of that money and effort invested in communications is wasted.

Social service organisations collectively spend millions of dollars each year on communications that focus on informing people. Sadly, these kinds of efforts ignore the scientific principles of what motivates engagement, belief, and behavior change. Consequently, a lot of that money and effort invested in communications is wasted.

Problem 2: Not enough meaning.

Problem 2: Not enough meaning.

Great, how am I supposed to remember all of this?

Great, how am I supposed to remember all of this? In addition to the four problems, it would be useful to remember these four truths about how our solutions to these problems have problems of their own:

In addition to the four problems, it would be useful to remember these four truths about how our solutions to these problems have problems of their own: