Don’t give up the fight – Digital activism in times of COVID19

Physical distancing doesn’t have to mean social distancing. Communities are more important than ever and physical distancing should mean getting socially actually closer.

May 17 will provide a key opportunity for this, and here are some ideas about how to make it happen.

There is an online collaborative version of this document so that everyone can contribute their ideas and share tips on how to organise these activities. We warmly invite everyone to participate

Crowdfunding

LGBTQI+ people are particularly vulnerable to the impact of COVID-19 as many are part of the poorest people and are already victim of many forms of discrimination, stigma and persecution. Funding is desperately needed and May 17 can provide a good entry point for a call for solidarity. There is an infinite list of resources on how to create a fundraiser. This article is a good place to start

One additional tip that we would like to offer: Underlining the vulnerability of LGBTQI+ people in the face of COVID-19 is important, but it is likely to get unnoticed in times when people are concerned mainly about themselves. A more effective frame to connect with people in these times could be to share advice and tips on how we, as a community of people who have been often forced to live in isolation from others (either physically or mentally), have learned to cope with this. Showing understanding and providing support (“This is how we can help you now. Help us to help you more in future”) could be an effective tactics to generate some reciprocity.

Flashmobs from home:

For May 17, a specific LGBTQI+ anthem can be played (and sung?) simultaneously by people at their windows. The information should be available early on online so people can get ready to join and the event should be well referenced so that when it happens curious people who wonder what is going on and search the net can find the answer easily.

- Cacerolazo: Banging pots and pans has been used around the world, more to express outrage than in order to voice support, but it’s been used these days also to support health care workers

Flagging:

People hang flags, posters or banners at their window or wear something identifiable when they take walks. More permanently visible than a flashmob.

For May 17, there could be a special hanging of Pride flags together with banners (or handmade “red cross” flags) supporting health care workers, both to show support and gratitude to health care workers in general but also to salute LGBTQI+ health care workers who risk their lives:

A gay man is the first nurse reported to have died of the virus in New York City, reports The New York Times.

Online community events:

Homo Sapiens is not a solitary animal. Forced to confinement, this species finds every possible trick and tactic to keep connected to mates. From Zoom yoga classes, Skype book clubs, Periscope jam sessions to Cloud Clubbing, the internet is rife with creative ways to keep engaged with others. Some of these can definitely be of inspiration to creative campaigners for May17

- Virtual church services

With online/TV/radio preachers all over the world, online services are nothing new. The challenge is to try to replicate the feeling of community, which makes services so important for worshipers. This tutorial offers a large range of technical advice

Here is one example of what this can look like

- Cloud Clubbing

Most clubs have now taken their parties online and DJ rely on voluntary donations to keep them afloat.

For May 17 it would be interesting to customise the party so that it has a distinctive flavor. For example there could be a “protest” dress code or playlist could feature plenty of protest songs. Looking for inspiration? Here might be a good place to start looking.

- Online performances

Cabarets, drag shows, standups, can all be taken online with a minimal technical equipment. But whole festivals can also be taken online, as for example the Digital Drag Fest.

This article reports on a nice initiative that brings drag artists from different countries together

- Meditation classes

Members of the LGBTQI+ community are particularly vulnerable to social isolation. Meditation can be extremely helpful to help people cope.

For May 17, a special event can be designed to help people overcome internalised stigma.

If you don’t have the ability to conduct a meditation yourself, you can organise a collective watching of free online meditations and psychology talks. I would personally recommend Psychologist, Bhuddist and Meditation teacher Tara Brach. Her inspiring talks are all free online on her site. Of particular relevance : Her talk on how to confront the pandemic fear and her talk on how to confront addiction. You can check many more meditation classes on the free and collaborative app Insight Timer.

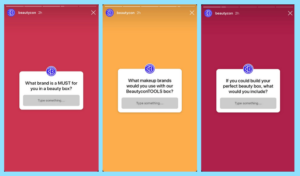

Start engagement journeys

The idea behind engaging supporters is that it requires GIVING before asking. So instead of asking people to like, share, sign, donate, etc., an engagement journey starts with offering something to the target group. At a time when the COVID-19 crisis has everyone yearning for ideas of things to do at home, to keep the kids entertained, to eat healthy, etc it could be a good idea to start by inspiring people.

For the whole week around May 17, global organisations could prepare a whole 7-day “anti-homophobia diet”, with recipes from around the world (or the neighbourhood!) that could be shared with the life story of an LGBTIQ+ person from this country. And why not go vegan, by the way, as an acknowledgment of the environmental damages that partly provoked the COVI-19 pandemic.

Or organisations could launch each day of the week leading up to May 17 week a quizz program which could, with minimal back-office management, lead to an “IDAHOBIT award”

Another idea is to tap into the specific experience and skills of the LGBTQI+ community and make other people benefit from. Drag artists could share make-up tips and tutorial. Non-Binary people could give gender-neutral clothing lessons, etc.

Live programs

Live programs (Facebook lives or online radio programs) can be a good way to connect people. Watch this tutorial if you haven’t organised one before.

Viewers/Listeners can be invited to call in and share their opinions or stories, which makes it more interesting than just listening.

May 17 could be a good moment to launch an online radio station, or at least a regular online event (e.g. on the 17th of each month), with a distinctive flavor that can keep a specific target group engaged (“17” could be appropriate to target young people)

“Collective” film screenings

Now movie theaters are closed and we can’t organise movie watching parties at home, there are other ways of creating that special feeling of watching a film with other people. This is pretty easy to organise on zoom.

With teleconf apps like zoom, skype, team, etc. you can also organise collective screenings through screen sharing, which can be more fun when watching a comedy, a sing along, a horror movie, etc.

These moments can become a good way to engage with your community members who usually don’t engage with you, either because they are too shy or because they are generally not interested in community activities.

For May 17, a special event can be organised around watching a documentary on a topic which you feel passionate about. If there is a silver lining to the COVID crisis, it is that a lot of community members have much more time and interest than before to engage in deeper reflections. We have started updating a list of documentaries we published some time ago that deal with many aspects of our lives. All these documentaries are interesting material to organise community discussions around.

Watching one of the fabulous films from that list that specially focus on LGBT activism can be a great way to make your audience gain more insights into the fascinating work that your organisation does, and maybe get them hooked to become volunteers.

And you have of course a host of LGBTQI+ themed movies to choose from. Take this list of 50 as a good starting point

Reader circles

More demanding that movie circles, reader circles invite people to collectively read a book, an essay or an article and facilitate a discussion, possibly also bringing in the author or selected authoritative commentators. This is a good upgrade from online events with no preliminary reading, as in these reader circles people start with a common framing of the debate, which makes conversations more relevant.

For May 17, a reading list can be sent in advance with a list of 7 topics that will be discussed during live event on each day of the May 17 week

An interesting list of books to get started

Offline virtual protests:

- Political art display

Creating political artwork is a great activity to do when you are stuck at home and want to express yourself.Some organisations like 350.org are engaging with their supporters and provide them with training kits for creative aRtivism. A clever way to keep people engaged and to get them to use this time of social distancing to develop new skills

When physical gatherings are not possible, it is still possible to show the power or people offline in other ways: gather photos made of individuals with signs, print them out and display en masse publicly at the specific target. Consider chalking outlines of participants.

For May 17, people can be invited to create artwork, which can be displayed either online or printed out by organisers and hung as a banner.

This can be a good opportunity to connect with a virtual political art making party. Check out this guide to making political art by 350.org

- Projections

Guerilla projections and protest holograms require just a few people, and often require no permit! Consider projecting a live feed of comments as well.

For May 17, a hologram demonstration can be a powerful way to show that sexual and gender minorities are respecting the lockdown rules but that freedom of assembly is, in the long run, not negotiable.

More ideas on how to make this happen on our Creative Campaigning Resource Center

Taking your conference online

If you were thinking of a conference or a panel discussion to mark May 17, taking it online might provide an opportunity to change the format, as lengthy presentations are not an option for an online event. These tips for creating lively panel discussions might seem basic but make sure you tick all the boxes.

Facilitation of the interaction with the audience will be all the more difficult online but here are some useful tips on how to make it happen.

Release your advocacy reports and research

Every year, many organisations choose May 17 to release annual reports on the situation of LGBTQI++ people, or other pieces of research and advocacy papers. This year, it might make sense to publish specific pieces of research on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the community. This report from Egale Canada provides inspiration for this.

Personal connections

Helping people connect to each other, not necessarily (only) to your organisation, is a powerful objective, and not necessarily easy. But some initiatives provide great inspiration for this. On Amnesty’s model of writing personal letters or postcards, May 17 can be a good moment to launch a virtual postcard campaign, inviting audiences to connect with people from around the world. The COVID-19 crisis can potentially be a powerful frame to connect people over. And this article provides advice on how to run such a letter-writing campaign

The global LGBTQI+ federation ILGA has just launched this type of campaign

This initiative from a former Trans inmate is also a powerful example, as is the Rainbow Cards campaign, which also provides inspiration

Sometimes the challenge can be how to deliver the messages to people in isolation, more than to actually get the messages written. In which case it makes sense to team up with LGBTQI+ organisations on various continents, which can also provide a great way to educate your supporters about the diversity of gender expressions and sexualities. The initiative can also be directed at specific minority groups in the country/area you are in, for example migrants/refugees. In that case it is important to team up with an organisation that works with them and channel the support messages through them. The organisation Freedom from Torture for example channelled the messages of support to migrants that their supporters wrote through the psychological support services these people accessed.

Collages

Inviting for contributions from you audience in order to create an original piece of work is a good way to build a sense of community

This lip-sync video on Lili Allen’s pop hit “fuck you very much” is a very old example of this tactic, but we still like it 🙂

Living Libraries

For May 17, you can invite audiences to dialogue directly with specific people. This can specifically draw users from “neighbouring” communities who are curious, but not yet supportive. Organisers obviously have to publish a very specific code of conduct (what questions/language are appropriate, protection of data, etc.) and make sure it is complied with.

Selfie contests

Arguably, selfie contests have been around for many years and campaigners had better find creative angles in order to make this kind of action still appealing but there are now a lot of special apps that can bring new momentum to this. Check some out here.

Here is an article with some ideas around this.

(Re-)Launch a survey

Many people are likely to still be under lockdown by May 17, unfortunately. So with more time on their hands, they might be more likely to respond to that survey you wanted to do, or on which you got too little feedback. A good moment to reiterate.

More resources

There is a lot of thinking and innovation taking place at the moment on how to react to the COVID-19 crisis. We are building the list below as we go. Please send us your suggestions on the collective working document

Digital Charity Lab: Digital projects for non-profits during the Coronavirus crisis

More Onion: Digital Engagement during COVID-19 crisis Webinar