Online course “Communications for Advocacy” in 6 languages

Sogicampaigns and the PITCH program (Aidsfonds/Frontline Aids/Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs) are launching a free 10-lesson online course on Communications for Advocacy.

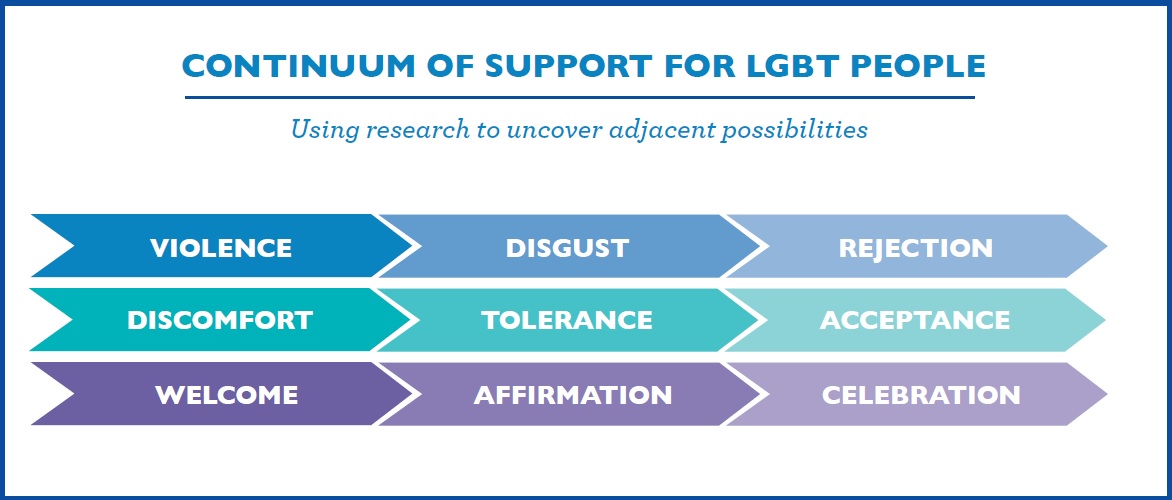

This course s based on insights of hundreds of campaigners worldwide and aims to help activists and advocates to truly engage, rally and influence people to their advocacy cause.

The course contains many examples of successful campaigns, many exciting and inspiring videos, interactive exercises, quizzes, and concludes with a 10-step plan to build your communications for advocacy strategy.

We encourage all creative campaigners to check it out: If you think your communication can be improved, it will give you many ideas and examples and will guide you in becoming more strategic about your communication. If you think your communication is already ahead of the curve, this course will help you test your assumptions, and maybe challenge you on some aspects.

Access the online course in English – Russian – Portuguese – Bahasa Indonesia – Vietnamese – Burmese