Memes as a campaigning tool

If you spend more than a few hours a day on the Internet (which, you must admit, is the case for nearly all of us), there are certain things you will come across wherever you are. On Twitter, it’s a food ordering site, on Instagram, some parody account. You can even find them on the hook-up apps. A smiling grandpa with gleaming teeth wearing doctor’s clothes a guy watching a girl pass by while another girl next to him labels him, as an evil Kermit … They’re everywhere. Literally everywhere.

What they are?

They are memes.

Defining ‘memes

This word seems to have crept into almost all languages. We communicate with memes more and more often. Whether it’s pointing out serious problems or just as a joke.

All righty! We will start, in an academic, nerdy manner, to first define what memes are, by consulting serious researchers and sources.

According to MW Dictionary, this word dates back to evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins’ 1976 book The Selfish Gene. In Dawkins’ conception of the term, it is “a unit of cultural transmission”—the cultural equivalent of a gene.

Meme found its place in dictionaries, from 2015, which define it as an amusing or interesting item (such as a captioned picture or video) or type of item that is spreads widely online especially through social media.

Okay, great, but not every digital content that gains popularity is a meme, right? There is a whole lot of fun contents on the internet, but not all of them are meme.s

So, another question arises – what are essential elements of a meme?

It is an extremely challenging to try to determine the anatomy of such an elastic and evolving concept as a meme.

There are several features.

- Reproducibility: digitally produced pieces of content must be infinitely reproducible and exploitable across a wide breadth of platforms.

- Searchability: finished versions of memes, as well as raw templates, should be easy to find.

- Scalability: digital material is created for a specific audience, but with the knowledge that it can be shared with a much wider audience, wherever the internet reaches.

- Persistence: although digital items may not last as long as physical objects, they are infinitely transferable and storable in many locations.

- Adaptable model: memes should have recognisable structures, with spaces for new content.

Maybe it isn’t very appropriate to say, given the times we are living in, but internet memes are probably quite comparable to viruses. They are dependent on living hosts, have the capacity to infect anything and everything, the ability to evolve, to mutate, to grow and, most importantly, to spread.

Because they are ubiquitous and very popular, everyone starts to use them. Just everyone. Businesses, politicians, celebrities … Even activists. Particularly activists! Quite simple to make and even simpler to distribute and disseminate; they can communicate a stance or message at a glance, revealing an issue in such a plain, yet appealing way.

As they have the tendency to spread quickly, constantly evolve and transform, it makes them hard to eliminate in the way that other forms of communicative protest can be silenced.

A wide breadth of international human rights organizations have recognized the importance and capacity of memes in combatting various types of discrimination such as racism, homophobia and transphobia.

Let’s take a look at examples of how memes have been used in LGBTQI+ activism

Political Satire

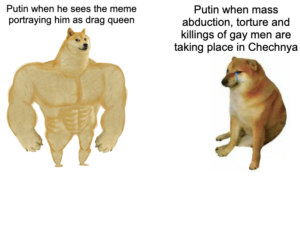

Do you recall “gay Putin” meme, that became viral in 2013?

As this altered image with lipstick and makeup gained popularity and mobilized the queer movement across Russia, it seems that the Head of State, either out of fear of massive, nationwide mobilization, or dissatisfaction that an internet meme which depicted him with mascara and rainbow colours disrupting his masculine image, started to crack down on both sexual liberties and online speech.

In the very same year, 2013, Russia passed its first “Internet extremism” laws. A year later, President Putin signed a law imposing prison sentences on people supporting banned online posts. In 2015, Russian law enforcement began shutting down websites of Putin critics, restricting virtually all anonymous blogs.

Eventually, in 2017, the Russian Justice Ministry included the “Gay Putin meme” in a registry of “extremist materials,” together with others such as anti-semitic and racist pictures and slogans. It became illegal to distribute the image of a Russian president wearing makeup.

The fierceness of the repression is a clear indicator of how powerful the Russian authorities see this new form of political satire.

Collaborative campaigning

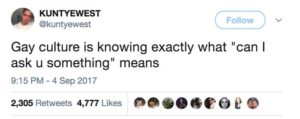

Another example is the “Gay culture is…” meme.

Queerty traced the meme’s origins to early September 2017, when one man’s tweet about his wasted teenage years went viral.

Immediately, Twitter users started producing content in the same format, expressing their own vision of what “Gay Culture” means to them.

The format here is different as the meme invites users not only to share a set content but to collaborate with personal inputs. This format is clearly the expression of the present age of activism that focuses more on active participation than passive sharing.

The final question that remains to be asked is whether memes be considered a ‘slacktivist’ tool, and if so – how strong are they really? In practice so far, it can be said that memes are possibly responsible for helping fuel ongoing discourse on many issues.

Current research suggests that internet memes play an important role in civic expression and citizen empowerment. Queer activists and campaigners have already leveraged this, and with certainty will continue to do so.

Creating your memes

And yeah, I’ve left the best news to the end – memes are very easy to make!

You don’t need knowledge about design, or be skilled in Photoshop. Just visit THIS website and generate your own meme. You can use some that are already popular or you can popularize your template – simply by uploading the desired photo.

If you want to make a meme out of a gif – just visit this website.

Good luck!

That instinct is described by communication theory as the

That instinct is described by communication theory as the

In November 2012, it seemed like the lyrics “Dumb ways to die, so many dumb ways to die” were leaking out of the iPad of every teen. The

In November 2012, it seemed like the lyrics “Dumb ways to die, so many dumb ways to die” were leaking out of the iPad of every teen. The  One of the most important tasks in crafting a public interest communications campaign is to identify your target audience—the individuals or groups whose action or behavior change will be most important to helping you achieve your goal. One of the best examples of this approach is a case that didn’t begin as public interest communications but certainly had lasting implications for freedom of speech.

One of the most important tasks in crafting a public interest communications campaign is to identify your target audience—the individuals or groups whose action or behavior change will be most important to helping you achieve your goal. One of the best examples of this approach is a case that didn’t begin as public interest communications but certainly had lasting implications for freedom of speech. It’s important to develop a comprehensive understanding not only of the audience you are trying to reach and what will resonate with them, but also of the complexity of the issue you are trying to affect and its context. It is particularly important to craft campaign messages, stories, and calls to action that do not threaten how an audience sees itself or its values. Research into how your target audience forms opinions and who influences them will also drive your communication strategy, directing you toward potential partnerships, messages, and stories.

It’s important to develop a comprehensive understanding not only of the audience you are trying to reach and what will resonate with them, but also of the complexity of the issue you are trying to affect and its context. It is particularly important to craft campaign messages, stories, and calls to action that do not threaten how an audience sees itself or its values. Research into how your target audience forms opinions and who influences them will also drive your communication strategy, directing you toward potential partnerships, messages, and stories. Identifying the right target audience and delivering a clear call to action that people will act on isn’t dark magic. It requires having a theory of change—a methodology or road map for how you will achieve change that includes objectives, tactics, and evaluation— and knowing the issue well enough to know where change will have its greatest effect.

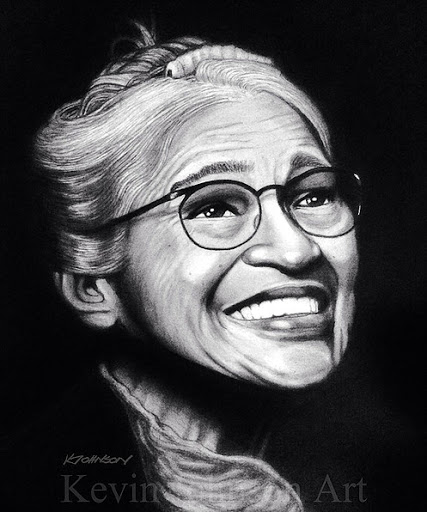

Identifying the right target audience and delivering a clear call to action that people will act on isn’t dark magic. It requires having a theory of change—a methodology or road map for how you will achieve change that includes objectives, tactics, and evaluation— and knowing the issue well enough to know where change will have its greatest effect. Robinson intuited something else that research would bear out decades later. Successful public interest campaigns need a narrowly defined audience, clear calls to action, and a theory of change. But they also need one more thing—the right messenger. Robinson knew that the community would support Parks in a way that they would not support Colvin. In order to inspire and persuade people to adopt a new behavior or a new way of thinking, having the message come from people who have authority and credibility in your audience’s world matters.

Robinson intuited something else that research would bear out decades later. Successful public interest campaigns need a narrowly defined audience, clear calls to action, and a theory of change. But they also need one more thing—the right messenger. Robinson knew that the community would support Parks in a way that they would not support Colvin. In order to inspire and persuade people to adopt a new behavior or a new way of thinking, having the message come from people who have authority and credibility in your audience’s world matters.