Getting Hope back into the picture

This paper appeared in Open Global Rights

Its authors advocate for a change in mindset of campaigners for Human Rights.

While some of their points are specific to “mainstream” Human Rights issues, that is issues with which a majority of people are theoretically OK but don’t actively support (like Freedom of Expression), some lessons hold true for campaigners for minority issues (i.e. issues that a majority of people does not support, like homosexuality in conservative countries)

Lesson 1

Talk about solutions, not problems. People want to be paired with positive stories and results, not stories of loosing victims. And by talking about problems, you reinforce their presence in people’s minds, making them sound more and more “natural”

Lesson 2

Talk about what you stand for, not what you oppose. People need a vision for the future. People need to see that we share a common vision. This is what will make them support your cause.

Lesson 3

Be part of the solution, not the problem: People need to see you as someone who brings an answer, not someone who brings trouble. It can be an answer to the conflicts they feel as several of their values are opposing each other. Or an answer to a grim society, etc.

Full article

For a human rights movement dedicated to exposing abuses, positive communication does not come naturally. But to make the case for human rights, we cannot rely on fear of a return to the dark past, we need to promise a brighter future.

Hope is a pragmatic strategy, informed by history, communications experts, organizers neuroscience and cognitive linguistics. It can be applied to any strategy or campaign. By grounding your communications from the values you stand for and a vision of the world you want to see, hope-based communications is an antidote to debates that seem constantly framed to favour your opponents, so that you can design actions that set the agenda rather than constantly reacting to external events.

A hope-based communications strategy involves making five basic shifts in the way we talk about human rights. This guide has been produced in collaboration with Thomas Coombes (@T_Coombes) to help you apply to any aspect of your daily work.

Shift 1: Talk about solutions, not problems

While the human rights movement will always have to expose abuses, we also need to show how to fix them. Positive communications are about talking about what we want to see, not just what other people are doing. It is much harder for leaders to excuse not tackling problems than it is to justify failing to implement solutions.

The danger of focusing all our attention on the worst crises is that people become inured to it. When we focus on the problem, we reinforce it in the mind of our audience. Or as George Lakoff wrote, “People tend to adapt to a new state and take it as a new reference point.”

The sense of a world in crisis pushes people into the hands of populists who offer them security, and a return to some imagined idealised past.

Caption: In India, the BJP’s 2014 Achche din election campaign promised that “Good Days are Coming”. If populist leaders are able to promise a happy future, why can’t human rights groups?

We need to convince people that another world is possible. Visionary ideas change the world, and people who put them forward set the agenda instead of being on the defensive. Campaigning against austerity measures, for example, are unlikely to make decision-makers act differently unless they make the case for a viable alternative, be it greater public investment or thought-provoking initiatives like Universal Basic Income.

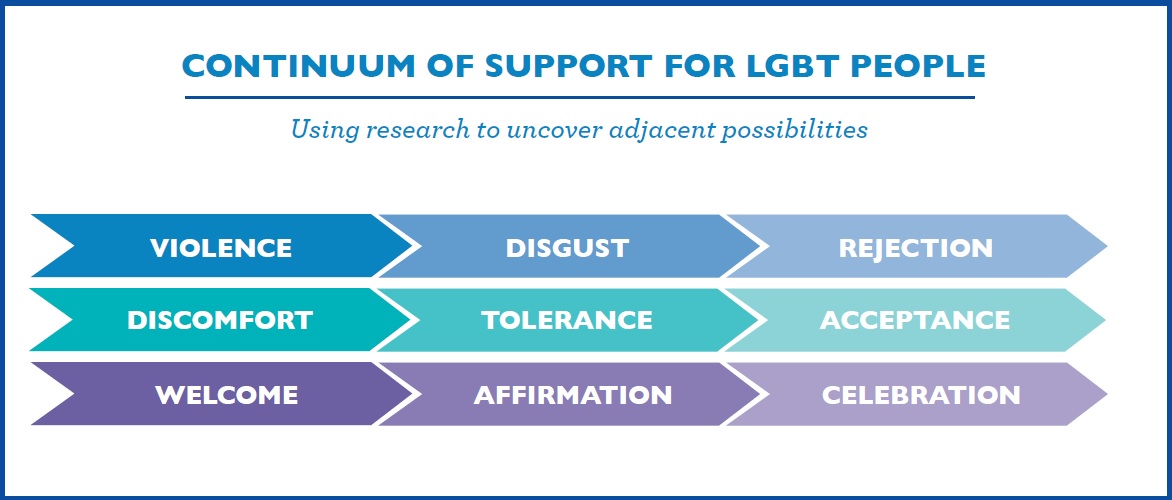

The environmental movement made this shift when it realized that stories of impending doom created despondency instead of urgency. The LGBT movement shifted from campaigns against discrimination to shared values by focusing on one of many possible policy solutions: equal marriage, a call rooted in love and compassion that everyone could relate to. If we want something to change, we need to stop just saying “no” to the problem, but give governments something to say “yes” to, by putting forward bold policies: smart human rights solutions that trigger debate, and showing what the desired transformation will achieve. Even in the darkest crisis, we can always focus on the first step towards the light at the end of the tunnel.

Shift 2. Highlight what we stand for, not what we oppose

The human rights movement should show how human rights is a practical application of universal shared values like compassion, solidarity and dignity, rather than defining rights by the absence of their violations (“a world without torture”, “protection from harm”).

The movement’s favourite expression today is “not a crime”. Journalism is not a crime. Refugees are not criminals. This fuses together the concepts of criminality and human rights in the minds of our audience, invites a debate about whether or not journalists are criminals. It’s no surprise, then, that surveys constantly show people think human rights protect criminals (nearly four in ten globally, according to a 2018 IPSOS survey). But worse still, it misses the chance to tell our audience what journalism brings to our society and propose measures to give us more of it.

Human rights advocates tend to do this because we believe that raising awareness is enough, that if we just let people know that journalists are being treated like criminals, we will trigger outrage and shame. Instead of name and shame, we need to name and frame. We need to call for what we want to see and spell out the shared values at stake.

Talk about the policy you want, explain how the government could do it, and explain what values it would be living by if it implemented them. Tell stories that build up our way of seeing the world without necessarily directly dealing with the issues we work on every time.

When human rights organizations talk about values, they tend to find justification for human rights in national values. But to find things that unite people around the cause of human rights, we should look beyond narrow national frames. Most “tribes” are “imagined communities” that require a common enemy to exist, something today’s populists are adept at exploiting. Human rights, as opposed to rights that accrue to national citizenship, require that people feel like they belong to a common human family. That cannot be constructed with any common enemy. We need frames that focus on the things that unite human beings, not those that keep us apart.

In new human rights messaging guidance, Anat Shenker-Osorio warns that “Evoking national identity brings ‘us/them’ top of mind and makes respondents less receptive to others’ rights”. Instead of saying “As Indians/Europeans/Christians, we believe in treating each other fairly”, Anat invites us to say “as caring people”. This bigger “we” cultivates a sense of belonging to a different, more universal identity: our common humanity.

If the human rights movement were to stop speaking within the frames of our opponents (security, the economy or other, national interests), what narrative would we shift to? What is the ideal human rights frame?

The human rights movement needs a new narrative. Today we operate in issue silos, tackling each right one by one on the merits specific to that case. As a result, wider audiences understand human rights as something that protects us, that we are “entitled to”, rather than something we can all use to make things better.

We tend to visualise what we are against, not what we are for: hands grasping bars illustrate injustice, but what does justice look like?

We should instead talk about a common, universal world view, a society where people take care of each other. A common world view that we can strengthen in the minds of the public day by day, story by story, tweet by tweet.

If we do not make the case for the world we want to see, who will?

Shift 3. Create opportunities, drop threats

When we talk about solutions, we give people an opportunity to be part of making things better, instead of using threats or guilt to make them act.

We need to reflect on the experience of being part of the human rights movement. We want to build, we want to take society on a journey to a better place, but when we talk we lean heavily on the language of conflict, which is divisive. Do we want people to think of us as fighters, radical and divided, defending the interests of the few, or builders, constructing something for all?

When we talk about human rights as protection from harm, our implicit message is based on fear and self-interest. These could be your rights. Imagine if your rights were taken away. One day it could be you.

But there is another way. We can appeal to the better angles of our nature. Human rights can connect people in solidarity. It can offer a chance to act on the human desire to be a good person, do the right thing, and help other people.

Successful movements are propelled forward by enthusiasm and passion. While Donald Trump united his base with the simple red baseball cap, ordinary people demanding women’s rights queued for hours to buy “Together for Yes” buttons in Ireland and thronged the streets wearing green scarves in Argentina. Symbols of belonging are not just about fundraising or powerful images, they create a shared sense of belonging that elevates a cause to something historical, momentous and inevitable.

But we cannot generate lasting passion and enthusiasm that pressures leaders purely through outrage and disgust: we must celebrate what we stand for. Joyful, inspiring content like Planned Parenthood’s Unstoppable campaign serves not just to inspire, it creates political momentum:

For people to hear our messages they need to see us as unifiers, people who build constructive solutions, people who will take them on a journey instead of fighters. We also need them to feel like they live in a less polarised culture, by contributing to a popular mood of togetherness and community—the ideal breeding ground for human rights friendly policies.

Indeed, more and more research points to the fact that fear and pessimism triggers conservative and suspicious views, while, hope and optimism tend to more liberal views. New research from Hope not Hate, for example, says:

“Where people are more likely to feel in control of their own lives, they are more likely to show resistance to hostile narratives, and are more likely to share a positive vision of diversity and multiculturalism.”

In Hidden Tribes, a 2018 report from More in Common, insists that the media landscape accentuates the conflicts but downplays the solidarity in our society. It advises us to find common ground to counteract the divisions magnified on our screens with stories of human contact and respectful engagement that “spotlight the extraordinary ways in which [people] in local communities build bridges and not walls, every day.”

Shift 4. Emphasize support for heroes, not pity for victims

Instead of inducing pity for victims, offer people an opportunity to side with heroes, and be a part of making change happen. Show them ordinary people who show extraordinary perseverance, determination and courage. Help your audience make connection to individuals, not groups, by highlighting the little details that everyone can relate to.

If we want people to be compassionate, show them other people being compassionate. Presenting people in a way that induces fear, pity and anger may also inadvertently contribute to dehumanisation. If a politician calls a group of people animals, do pictures of those people in cages reinforce that metaphor? Faced with dehumanizing politics, human rights must do everything it can to re-humanize people.

A focus on re-humanizing people as an end in it itself opens up a whole new avenue of potential strategic operation for human rights campaigns, in which organizations pursue attitudinal change that would make possible a raft of policy improvements. We can focus on telling positive stories that will change attitudes towards the people we are trying to help.

More in Common research in Italy identifies not only fear of migrants but also a sense of solidarity and a disgust with racism, arguing for the need to strengthen values of hospitality and empathy, demonstrating “the real-world integration stories of migrants into Italian cultural life—in areas such as language, sport, food, community activities and entertainment.”

These kind of insights can be the basis for targeted content that tells humanising stories to specific audiences based on their values and interests, like the Swiss NGO that served up YouTube ads introducing refugees to people before they could watch racist videos.

Much of our audience has in-built stereotypes about “other” people, that sometimes will not be changed by hearing their story. But, as the HeartWired guide for change-makers written by communication strategists Amy Simon and Robert Perez notes, we can open them up to change by showing them someone like them engaging with the “other” and changing their mind.

The HeartWired approach’s focus on changing mindsets offers a new long-term strategic goal for human rights communicators – focus on campaigns that bring about long-term shifts in attitude towards other groups of people.

People who change their minds and decide to help are also heroes, as in this powerful for add for marriage equality in Ireland where the heroes are traditional parents supporting their children.

These are also stories of a changing society, stories that show how change happens, and offer a glimpse of the world we want to see.

Practically, this means creating social media moments based on interactions between people, that organizations can package as b-roll and images and send to digital news organizations like AJ+ and NowThis News, changing the narrative from “us vs them” to one of humanity. A Danish travel agent used DNA to show a group of people how much they had in common, Heineken asked people who were very different to build a bar together, and Amnesty International Poland asked refugees and Europeans to look in each other’s eyes for four minutes.

We are in a world where the majority of people want to do the right thing. But crisis and conflict-driven media narratives paint a different picture. We need to tell stories that reinforce the human rights worldview—where people take care of each other, and stand up for the rights of people far away just because they are all human.

Above all, we need to tell stories of humanity and compassion, thus reinforcing the idea that human rights are about people standing up for each other. We need stories that put the human in human rights.

Shift 5: Show that “we got this”!

Political strategist Mark McKinnon says all campaigns are either a narrative of hope, fear, threat or opportunity. How do we talk about hope and opportunity when human rights defenders are under attack and we need to defend ourselves, to fight back?

We need to stop talking about human rights under attack. That makes us seem like a losing cause and who wants to get on a train going in the wrong direction?

You light a candle when its dark, and you need human rights most when they are absent. Human rights defenders have “long been on the front line”, but frames of crisis and peril can inadvertently harm perceptions of the movement’s effectiveness, as Kathryn Sikkinkrecently argued.

People want to be part of something successful. Amnesty International France are running a “Thrill of Victory” campaign to associate the words “Human Rights” with “victory” instead of “problem” or “violation”.

In her pioneering study of human rights language, Anat Shenker Osorio urges the movement to display a quiet confidence:

“Where white nationalism offers an explanation and antidote for what feels like the world spinning out of control, human rights often provide a storyline that cements the feeling of unrelenting and accelerating change. Although the human rights paradigm is, by many measures, about order and known outcomes, the sense that “we got this” or there could be some steady, reliable, normalcy rarely comes from human rights.”

To show that “we got this”, we need to show more human rights in action. What does it really mean to do human rights and what does this look like? What is the picture we want people to have in their head when they think of human rights, human rights defenders and human rights activism? For some, this might mean holding protests, calling up politicians and writing letters to political prisoners for others it could be people coming together at community events or cultural moments.

Whatever they are, the activities the human rights movement undertakes need to tell a story of change, and show that human rights are not just a thing that we are born with or passively receive from governments, but something we do: a tool for making our societies better or a way of living together. Describing human rights as actions helps indicate that we must constantly make choices to cultivate and grow them.

Moreover, we need to change the expectations and associations with the very words “human rights”, explaining them as a metaphorical “tool” that we put in the hands of ordinary people to make change. Anat Shenker-Osorio’s research provides several avenues for further testing: Is human rights a shield or insurance policy that protects people from harm, a map or compass that points us in the right direction, or string or glue that binds us together in our common humanity? This way of thinking about human rights can not only inform our messaging, it can revolutionise the way we human rights and other organizations carry out their mission.

There is hope for human rights. People share our values and they want to do what is right. We just have to get better at activating those values, and talking to people about them.

These shifts will feel unnatural to many in the human rights movement. But the evidence shows they are the path to victory. And human rights is too important not to do whatever it takes to win.