Will truth be defeated? What can be done when 12 million Americans believe Obama is an alien lizard?

On February 12, 2014 the New Zealand Prime Minister proudly announced on TV that he could medically prove that he was not a …lizard.

Although this made everyone laugh, the sad truth is that he had to respond to a constitutional request of a citizen who demanded that the PM proved that he was not “a lizard alien in human shape trying to enslave the Human race”. And sadder even, he was not alone. In 2013, 4% of the US populations (that’s 12 million people), believed the alien lizard myth, and that Queen Elisabeth and Barack Obama were among them.

Funny?

If you draw a parallel with the myths and urban legends surrounding LGBTI people, it is not. “Abuse of children”, “witchcraft”, “demonization”, are just a few of the myths that are being used to persecute, and often kill, LGBT people. Hardly is there an earthquake that is not blamed on “gays”, in places as different as Italy, the USA, Haiti or more recently Indonesia.

From firm belief that planet Earth is flat, to certainty that HIV can be cured with garlic, there are countless urban legends and myths that resist all forms of argumentation.

Some campaigners will argue that it is education to rationality that will over time overcome legends and myths. But if education might be a necessary condition, it is by no mean sufficient. Actually, in a lot of cases the more educated people are the better they are equipped to justify their beliefs. Education might make it more difficult for people to hold crazy beliefs but once they do, they will use their education to cling to them even more.

That is one of the reasons why having our campaigns systematically target “people with higher education” might be something we should put serious research in, and not just assume that they are more progressive, or easier to convince.

Social research into human behavior has shown that people make their distinction between true and false, or right and wrong, on the basis of the group they (want to) belong to, and not on the basis of what they know is true. Hence religious dogma and “alternative facts”.

And with the choice of communications channels being more and more in the hands of the users (no more sitting in front of the 8 o’clock news), people live in a social bubble and the influence of the “in-group” is getting stronger and stronger.

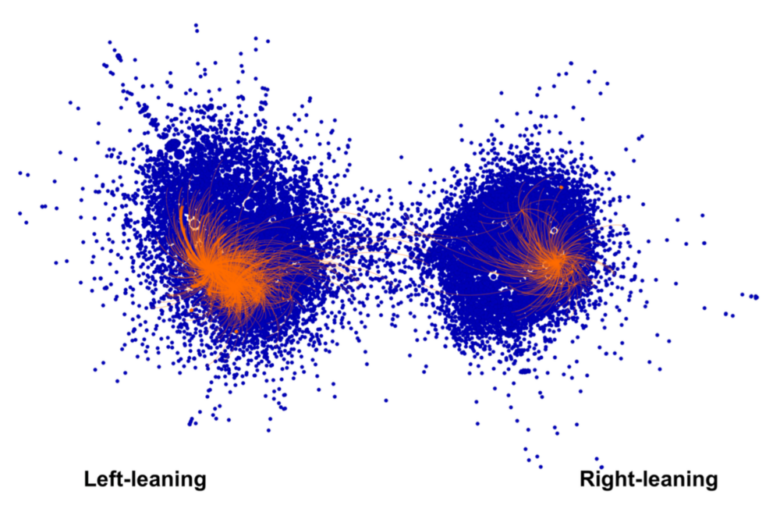

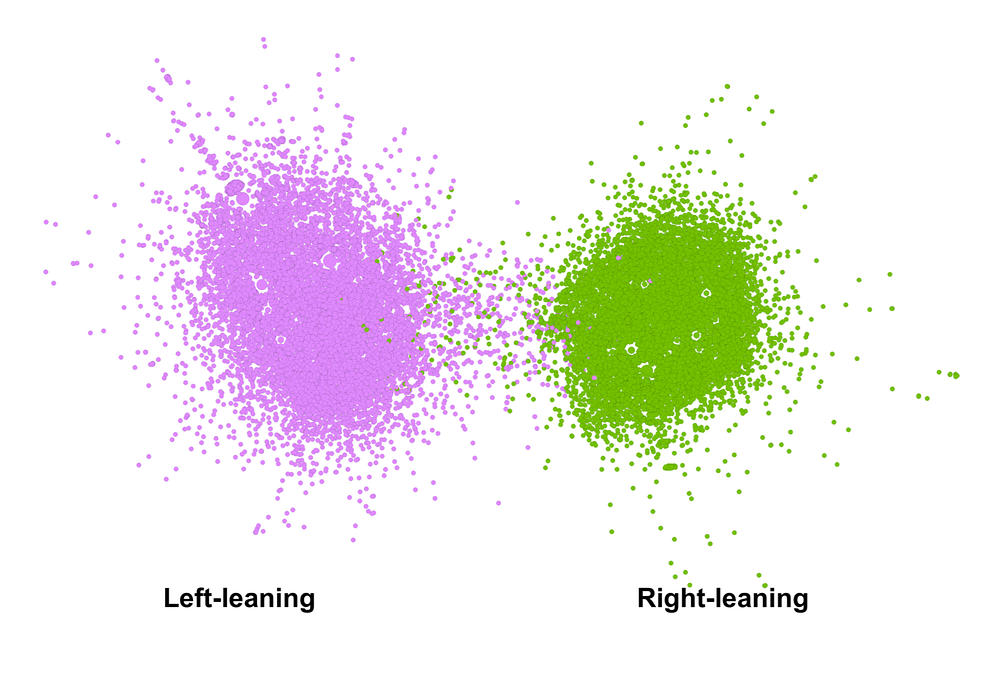

Social media research shows that the bubbles are tighter than ever, with very little flow between opposing bubbles.

So your “truth” is unlikely to reach your target in the first place. And if it does, it is likely to be dismissed.

So is truth once and for all a loosing game?

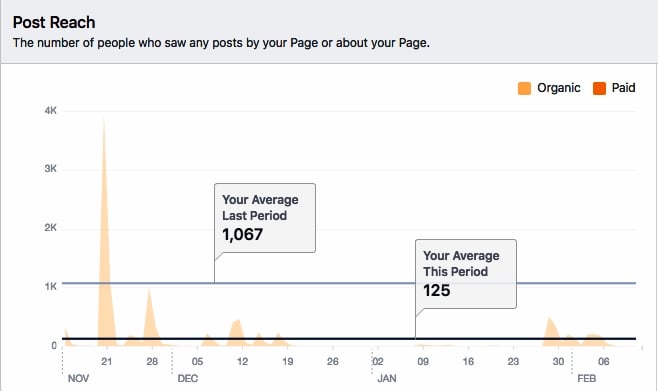

“Providing information” and doing so on one’s Facebook page is definitely not the most effective thing to do when it comes to changing people, but there might be some other options to consider:

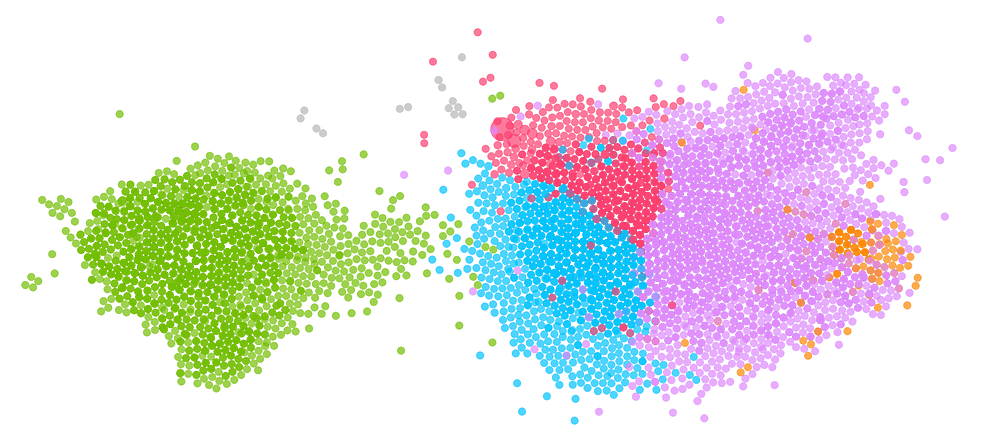

The most obvious move is of course to reach beyond your own “bubble” and identify the “bubbles” that are closest to you: the first tier. Human rights groups, women’s liberation forums, and all your natural allies.

But some of the “second tier” bubbles are harder to identify, although this is often where the biggest gains can be achieved. If you aim at early adopters of new trends, discussion forums on technological progress could be a good target. If you aim at young modern women, you might want to try discussion forums on fashion or modern lifestyle. When you know that a new series with an LGB or T character hits the net, it might be a better use of your time to participate in the discussions on mainstream discussion forums rather than on your own channels.

But even so, the basics of campaigns communication still apply and aggressively trolling these circles will be counterproductive, only alienating enemies even further. Communication has to be smartly framed, and this takes a bit of preparation.

Counter-intuitive as it may be, “truth” won’t change people.

If we want to have even a slight chance to change hearts and minds, we have to be good at becoming part of our target’s reference groups. And this requires going out of our bubbles and take the conversation where people are.