From megaphone to mosaic: five principles for narrative communications

By Alice Sachrajda & Thomas Coombes

from “The TILT, Reframing Human Rights for the 21st Century”

How can civil society groups and charities apply narrative work in practice? Based on our work with migration groups in the UK during the pandemic, we believe a crucial step is more narrative synergy between organisations that share the same values. Scroll right to the end for practical steps and more information about how you can get involved in collective narrative change.

Have you ever looked closely at a detailed painting and then slowly stepped back to see the picture take shape and come alive before your eyes? It’s a magical feeling when the smaller component parts complement each other and align to create a unified whole. This is what happens with an intricate mosaic, where small individual tiles collectively merge to create an image that is striking to behold.

The same synergistic principle applies to narratives. We communicate by sharing our messages and stories, but it is their accumulation over time that form lasting, memorable narratives. When we communicate strategically we need to think not just about how we craft our own message, but also how we are adding to a greater whole and strengthening shared narratives in the process. In short: to be strategic we need to be synergistic.

As the Narrative Initiative writes:

“What tiles are to mosaics, stories are to narratives. The relationship is symbiotic; stories bring narratives to life by making them relatable and accessible, while narratives infuse stories with deeper meaning.”

Elena Blackmore, writing for PIRC, has also used this metaphor to powerful effect where she writes perceptively about #BlackLivesMatter and the response that is required to change harmful narrative mosaics:

“This is the narrative mosaic of white supremacy and it comprises hundreds of years’ worth of tiles of violent history. We can understand a narrative in this way: as a ‘coherent system of stories’.”

If communications work is about crafting the right kinds of words, visuals and feelings to get a message across, then strategic communications is about stepping back and thinking about the big ideas, attitudes and behaviours we want to shift. This means thinking not just about promoting the work of our own organisation, but choosing the right stories to tell about what is happening in the world today. This means communications based more around moments than on campaigns.

These reflections are based on recent work with Unbound Philanthropy and Migration Exchange during the pandemic. We have been working to help activist groups apply narrative messaging around Covid-19 produced by communications experts such as Anat Shenker-Osorio, PIRC, Frameworks Institute and IMIX to their daily work. And we have been having deep conversations about narrative change through our Narrative Working Group (NARWHAL) convenings, curated by Phoebe Tickell.

Thinking of narratives as mosaics leads us to collective communications strategy

If a narrative is a mosaic, our communications must build it up tile by tile.

Every day is a new opportunity to find new tiles to add. These tiles can be planned and created by your organisation. They might also come from an ally or from grass-roots supporters.

Creating new, striking narrative mosaics requires as many people as possible offering up the same sorts of ideas, creating images that bring to life our shared values and exchanging stories that reflect our worldview.

We have designed a messaging house to help guide this process, drawing on the idea of a Larger Us developed by Alex Evans at the Collective Psychology Project as a way of articulating what unites groups working on human rights, environment, poverty, racial justice and others in common cause.

This messaging house contains simple “common sense” ideas that we can all repeat over and over again, and bring to life in stories, videos, drawings and graphics (find out more about the messaging house by scrolling down to the practical steps below).

We use a messaging house applies the mosaic principle because rather than asking every group to use shared branding or slogans, we instead invite everyone to inject a little bit of the spirit of our shared worldview into their work.

Applying mosaics-thinking to our communications strategies is crucial if we want to change narratives.

Getting the wording of our messages right is important, but communications is often about more than words: it is about images, stories and emotions stirred by cultural products.

Five principles for creating narrative mosaics with strategic communications

There are five principles we’ve learnt from mosaic-making that help us to get to the heart and soul of strategic communications. We explore and unpack each of these principles in more detail, below:

- Principle 1: We need to unite around shared messages that capture the spirit of our communication. It takes many different tiles to make a mosaic. If all our tiles relay conflicting messages, our tiles will simply form a blur from which no narrative emerges. Only by constantly reinforcing a complimentary, shared worldview with stories and frames on a daily basis can we make our narrative salient enough to stand out.

- Principle 2: We need to capitalise on key moments that arise — tapping into the zeitgeist, rather than purely relying on engineering the focus. Mosaic-makers innovate all the time. We need to be open to raising up what works and what resonates in response to key moments.

- Principle 3: We need to build up powerful bonds of reciprocity. Building a mosaic is about elevating and building on motifs that work, and generating new, iterative content as a result. Reciprocity builds strong supportive networks, helps to further the message of a Larger Us and demonstrates that we are making progress together.

- Principle 4: Apply the rule of thirds. There is sometimes magic to be found in placing the subject off-centre, resisting the urge of pushing problems to the front and centre.

- Principle 5: We need to accumulate multiple stories and messages. Mosaics are created by adding together multiple smaller parts, some of which are plain and reinforcing, peppering our communications with bursts of creative inspiration. Sometimes we need to experiment many times over to hit upon a powerful message that truly resonates. Everyone can add their tile to the narrative mosaic, even by retweeting another post or asking your supporters share some positive news.

Principle 1: Uniting around the spirit of shared worldviews

Andamento is the ability to capture the mood and ‘feel’ of the overall piece, described as follows by one mosaic expert:

“Never mind the design — a design is a design — but pay attention to what is going on in the background of a mosaic and it is there that you will find the melody, the choreography, the spirit of a mosaic.”

The same applies in our strategic communications: Messages are important, just as the design helps to create the overall picture; but it is also vital to capture the ‘andamento’ i.e. the spirit or the overall ‘feel’ of the piece. This is about more than just crafting and framing our words and projecting them out to all who will listen. Instead, it’s about working together, collectively, to achieve a bigger, shared objective: It’s about making our communication fizz with energy and sing out in symphony.

The message of ‘a Larger Us’ needs to be at the heart of our strategic communications work. It is more than just a design feature; it is the ‘andamento’ — the spirit that should pulsate through all our communications.

Many campaigns start from a ‘them and us’ frame, and there is power in mobilising people to join a side who share a common enemy or opponent. But we are not as polarised as we might think. The vast majority of us are kind, well-meaning individuals who can unite around shared, transcendental values built on love, kindness and care that need to be at the heart of all our messaging if we want them to be more powerful factors in our politics.

The team at PIRC has done tests showing that thinking the best of human nature helps support for social change. Rutger Bregman, author of HumanKind, reminds us of the goodness of human nature and warns us that pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy:

If you look at empirical evidence then you find that assuming the best in other people gets you the best results.”

Covid-19 has taught us that we are all in this together. If we want to highlight just how marginal extremists really are, we must proportionately balance stories of extremism with those that show we are part of a Larger Us, rather than a ‘them and us’.

While we have to counter the threat of extremists, calling them ‘the opposition’ or ‘the other side’ gives credence to what is a minority view, worthy neither of these terms, nor of a dominant place in our mosaic.

Elevating the voices of those who share and express the message that we are united, connected and hopeful is kryptonite to extremists who seek to divide us.

Principle 2. Thinking in moments, rather than campaigns

Signature campaigns are one way to change narratives, but small, daily stories that capture people’s attention and create a “word of mouth” buzz are vital tiles that add to narrative mosaic. Rather than international theme days and other planned events, these stories and content are relevant to the spirit of the times. On social media these are known as “moments”.

Moments have the added benefit of authenticity. Moments are not just a condensed part of a news cycle, they are something happening in people’s lives. Campaigns, by contrast, are something we plan inside our organisations. Moments can be an influential figure like the footballer Marcus Rashford taking a stand on a principle like free meals for children from poor families over the summer holidays or K-Pop stars ruining a Trump rally. Or everyday people doing something that gets people talking, like banging plates on their balconies during Covid_19. These moments tend to capture the zeitgeist of a particular time, and reveal something we already know or feel about ourselves and our societies.

The significance of moments is that they act like a spark in a tinderbox. They ignite passion in people and can often be the precursor to political or policy change, and in some cases can go on to create powerful movements, as we saw with #MeToo, #TimesUp and more recently with #BlackLivesMatter. We need to be ready to spot and amplify these moments when they arise. This means finding unusual allies, acknowledging the power and influence of public figures and recognising the significance of popular culture in catalysing social change.

We also need to sustain these moments and make sure that changes are woven into the fabric of our systems and structures. In particular, we each have a a duty to ensure that racial justice is woven into our conversations about narrative change.

Principle 3. Building up powerful bonds of reciprocity

Behavioural scientists often remind us of the intense power of reciprocity. It is one of the strongest social norms we have in our society. As Matthew D. Lieberman, author of Social: Why our brains are wired to connect, reminds us:

“If someone does you a favor, you feel obligated to return the favor at some point, and with strangers we actually feel a bit anxious until we have repaid this debt. This is why car salesmen will always offer you a cup of coffee.”

We can use this intuitive need to reciprocate with one another in our communications. If you want others to elevate and share your work, start by doing the same for others.

No one organisation can make a narrative salient by itself.

Even if you can secure coverage in a big news outlet, or the support of a celebrity influencer, it takes sustained repetition of ideas across multiple channels and platforms to achieve salience. We all need to share each other’s stories and content for it to have a chance of impacting how people think, feel and behave.

Organisations, activists, artists and other people who share common causes can together create and source content that contributes to our narrative mosaics. This is about reciprocity: we all need to repeat each other’s ideas for them to become “common sense” narratives that people internalise and share. No organisation can, or should, try to produce this flow of content themselves, nor should they think they can distribute that content wide enough on their own. When we see something that reinforces our shared ‘Larger Us’ worldview from another messenger, we should flex every comms muscle we have to make it seen and talked about.

Fortunately, myriad NGOs, charities and movements do not need to agree to the exact same talking points, slogans and hashtags. But they can articulate a shared vision and basic values they are working towards. All the different stories, reports and other outputs can then reinforce our shared idea of how the world works and should be. In other words, we can agree what we want the mosaic to look like, and then create tiles of our own that contribute to it, in our own different ways.

Principle 4. Give your subject space to breathe

Artists often work to a ‘rule of thirds’ principle, and mosaics are no exception. The act of off-setting the subject paradoxically helps to give it greater prominence. We can learn from this principle in our communications work. By off-setting we give our subject room to breathe.

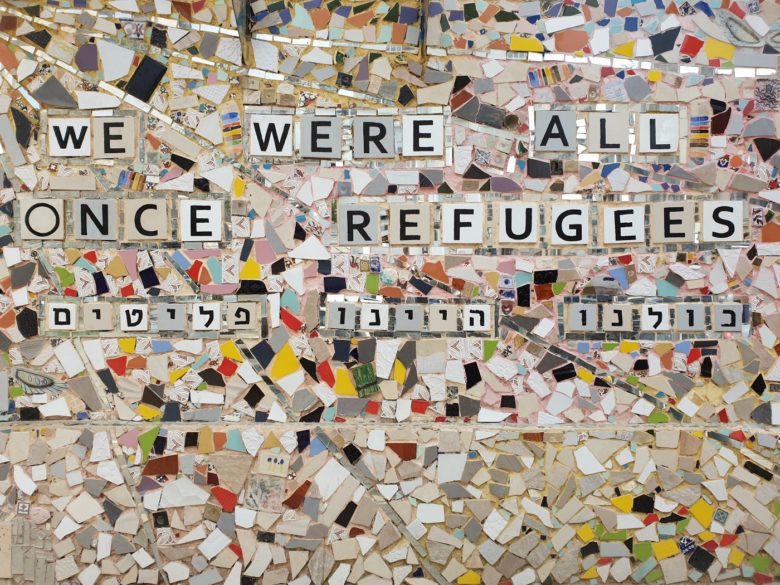

Mosaic-makers create impact by moving the main focus of the design at least one third of the way towards the edge. Communicators can learn from that by not always pushing political divisions and social problems to the fore, but letting them sit slightly to the side of more personal and multi-faceted stories, in which the people affected by problems are not defined solely by them. This draws the audience in, touches them on a more emotional level and allows them to feel empathy, rather than pity, for the people we want to support. People who have moved to a country generally want to be seen as people, not as migrants or refugees. Make the audience care about the person first, and then invite them to relate to the situation.

In the new series New Neighbours about newcomers to Europe and the people who welcome them, the story is about the emerging relationships. The issues are there but they are not foregrounded, allowing alternative possibilities to become apparent.

Principle 5. Accumulation of stories

As George Lakoff teaches us, if your communication is based on narratives you disagree with, you risk reinforcing these negative narratives. He encourages us to make the moral case for our positions with the same values that we want to activate in all audiences, built on empathy, responsibility and hope. We know that critiquing stereotypical stories only reinforces them, that we need a flow of surprising stories that create a mosaic of tolerance and appreciation for others. In today’s media environment we can elevate myriad voices and empower people to tell their story, their way.

It’s the accumulation of different stories that makes a narrative. We should think of our communications outputs as tiles that need to be true to the spirit of the mosaic that is our narrative and our values, rather than a single canvas that needs to be perfected like a masterpiece. You cannot fit the whole mosaic on one tile, and not every story needs to capture every aspect of an issue.

We can share one story of a successful refugee, one story of a migrant who is helping out, just getting by with help from the community, and another who is grateful, if that is the emotion they themselves want to express. We also need stories of people who are not on the move, but are welcoming to those who are. Just as individual tiles need to be true to the spirit of a mosaic, we can be guided in selecting these stories by our own values, basic ethical guidelines and a desire to let people speak for themselves.

Practical steps for a mosaic-movement approach to narrative change

Step one: Agree on simple messaging

The first step is a set of shared messages, leading with the same values. The specifics of our messaging may vary for different audiences and contexts, but there are universal ideas and values that we all identify with. Articulating these will help us to respond to what is happening in the world today — to “message this moment” in the words of Anat Shenker-Osorio.

That is why we designed a simple messaging house to describe the ‘Larger Us’ messaging that ties together the values underlying migration work with other causes like climate change, social and racial justice and equality and inclusion.

We find this format of the messaging house helpful because it focuses attention on one, predominant umbrella message (in this case a Larger Us) and then explores three sub-messages that help to strengthen the overall proposition.

A messaging house focuses your communications on the ideas you want to get to get across, rather than reacting to the loudest voices or being derailed by cynical questions. It is built around our values so it can be applied to any issue or situation, keeping you “on-message”, as well as “on-narrative”. The fact that we are all connected to one another as human beings is just as important a principle to climate change as it is to migration and racial justice.

Do take a look at the messaging house and see how you can apply it to your work. There is even a blank version you can use to adapt and apply the ‘Larger Us’ messaging to your own communications. We are happy for it to be an iterative tool and we welcome you to use it and add your comments, adjustments and input.

Step two: Organize content creators

Messaging is the starting point, but we need more than words to reach a mass audience. We need to elevate the actual stories happening in the world today that illustrate our messages without needing to use our jargon.

To that end, we can organise our supporters to be our chief storytellers. You can send them this simple cheat sheet to explain what kind of stories they can tell. That way, when they see a moment, for example, of cooperation between communities, they can take out their phone and tell the story themselves on social media. You can then elevate the best ones.

Creative artistic content can also bring our messages to life in emotive ways that may resonate with people the way political messages do not. A creative brief for cultural creators can inspire the people who can paint more beautiful tiles for our shared mosaic. For example, you can give artists and designers who want to support our cause this creative brief to articulate what you stand for, but leave them the creativity to bring those values to life in their own authentic way.

During the pandemic, for example, Fine Acts commissioned artists around the world to create small, simple works of art that would inspire hope, inviting people to print them into posters and sharing on social media. They are now curating works in support of Black Lives Matter.

Dancing Fox has a new project called “We were made for these times” combining art and stories that help us imagine a better world. To make people believe in the things we are calling for, we need the help of creative people to help them visualise what society will look like after our solutions are in place.

Step 3: Gather and curate stories

When we see a moment that reinforces our shared narrative, we need to get people talking about it. And we also need to ensure that we have a diverse range of people telling and sharing their stories. Getting news media to cover those stories is a crucial step, reaching new audiences and giving them credibility. But once we secure that coverage, we need people to share that news story. Getting the media hit is only half the work, we have to push it out on social media to drive “word of mouth” buzz around it if it is to become a salient “moment” that grows our narrative mosaic.

You can add stories you think will build up the ‘Larger Us’ mosaic in this story bank, whether you see them in the news or hear about them happening at grass-roots level.

For example, the Relationships Project has created the Spirit of Lockdown storybook to gather “the moments when we’ve noticed one another, as we have seldom noticed before.”

You can share stories that are already in the story bank, as well as stories you see from other activists and organisations, through your personal and organisational social media channels. You can use this messaging.

Step 4: Salience via distribution

We want as many people as possible to see the videos produced for the Britain Connects and New Neighbours series because they encapsulate the idea of ‘a Larger Us’. We should be sharing them through organic social media posts, sending it to others to ask them to share as well and even buying ads of our own to make sure more people who are likely to share them further also see them. That is how positive narratives around migration will become salient.

If you have the resources, you can also run social media adverts to make sure people see and share the stories, running ads to these audiences we feel are most likely to share positive migration stories. Erica Chenoweth has written that successful non-violent civil disobedience requires activating only 3.5% of the population. We can use that same principle in trying to target the stories we want shared to those most likely to spread the word.

Ask your supporters, friends and allies to add tiles of their own. You can use mail-outs and whatsapp groups to ask them to share on-message stories with their friends. We can have a greater impact encouraging a wide community of people to share the same sorts of stories. The smallest, simplest small stories from their daily lives are all small stones that make up the mosaic.

An implication of this approach is that we also focus audience research on our closest supporters, not just persuadables or extremists. Our base, after all, are the people most likely to articulate our narrative to other people and bring it to life through their actions.

In summary, civil society and charities need to be better at working together to make the most of the resources we have at our disposal to get the message out. In the words of The Narrative Initiative we need to “connect a narrative “nervous system” of collaborators.”

Are the press releases, tweets and videos we put out every day contributing to a shared mosaic, or are we simply all tiling our own bathrooms? If we want to change narratives, we can start by working together, particularly at the level of communications team. For example, the network of the people who actually run the social media accounts of the world’s biggest international NGOs set up earlier this year by Valeriia Voshchevska and Dante Licona is a perfect space to achieve reciprocity in our communications.

What happens next?

We can all work together to share values of empathy, kindness, equality, inclusion and solidarity. We can do this through a list of ‘Larger Us’ social media influencers who all agree to regularly share stories that are on-message. We can funnel stories to this list by getting grass roots organisations and cultural groups to see this as a resource when they want to elevate their work.

As a first step for building narrative reciprocity, we have created a common global space for anyone who wants to build ‘Larger Us’ narratives. If you are interested in our ideas, please share your thoughts below or get in touch here. We look forward to hearing from you!

Problem 2: Not enough meaning.

Problem 2: Not enough meaning.

Great, how am I supposed to remember all of this?

Great, how am I supposed to remember all of this? In addition to the four problems, it would be useful to remember these four truths about how our solutions to these problems have problems of their own:

In addition to the four problems, it would be useful to remember these four truths about how our solutions to these problems have problems of their own: