On 5 December 2022, the Russian president Vladimir Putin signed a new law prohibiting “propaganda around non-traditional sexual relations and paedophilia.” For several months previously, a group of activists had been campaigning against the law.

They called their campaign “People, not propaganda”

It was a collective campaign involving many different actors: individual activists, groups and organisations. We talked with two activists and members of the working group: Eva-Lilith Tsvetkova (they/she) and Margarita Shafranskaya (he/she/they).

What was the background context when you launched the campaign?

In 2013, the so-called “anti-propaganda law towards minors” was adopted. It outlawed any public expression of sexual and gender diversities, on the basis that anything public could potentially be viewed by minors. Since then, there had been several attempts to make the law more far-reaching and this time it seemed quite likely that the amendments would be passed. This was a tactic to distract public attention away from the real problems related to the launch of the war on Ukraine.

Within the Queer community, where people are often empathetic towards Ukrainians, the mood was one of profound grief and sorrow.

How was this campaign prepared?

Although the campaign was launched in October 2022, preparation started much earlier – in late Spring 2022, about the same time as the first draft of the new law was published.

We took inspiration from the process adopted in 2020, when a broad alliance led to the defeat of a Transphobic law.

The idea was not to link this campaign to any particular LGBTIQ+ organisation or group, but to develop it as a movement. The difference is that movements can have multiple leaders and people can also join as individuals. We thought that in this way we could involve more people. In addition to our usual allies, we especially encouraged participation from those who do not consider themselves to be activists and are not interested in joining organisations.

One of the challenges the campaign faced was that some people or organisations were not willing to be publicly acknowledged, and so a branded campaign would have given the credit to only some of the organisers, leaving others invisible.

How was the campaign managed? Was there ground control?

There was a management team which, importantly, was composed not only LGBTIQ+ people but also non-LGBTIQ+ activists. Throughout the summer of 2022, we had calls nearly every week to discuss what the campaign might look like, so when the law was submitted to the Duma (the lower house of the Federal Russian Parliament), we had already done a lot of groundwork and could quickly organise ourselves to launch the campaign.

It was a successful approach but it had one significant drawback: the number of people actively involved in the process from the very beginning was around two or three dozen, and after several months of such intensive work we were all pretty exhausted.

Also, some people started having issues with the authorities, and this led to a general feeling of insecurity and anxiety.

The specifics of our inter-organisational team led to some difficulties because of its unusual nature. Campaigns are usually created by one or more organisations, rather than by a group of activists from different places. We had some communication problems and misunderstandings but in the end, we managed to resolve them.

How did you come up with the campaign title?

We picked the title because our main message is that this is not just about “LGBTIQ+” people, it’s about people in general.

In 2013, we led the “People are not propaganda” campaign, whose main message was that a person cannot be propaganda for anything.

We used this message as inspiration for our new campaign because the current situation is in a way a consequence of what happened in 2013. They managed to pass the original law then, and that’s why we are facing the threat of this new law now. The dehumanising of LGBTIQ+ people in Russia escalated when this law was passed.

Our title “People, but not propaganda” focuses on people and their importance. Even if someone believes that speaking out about one’s identity might be considered as propaganda, it doesn’t erase the person’s value as a human being. This also reflects our aspiration to involve activists from other spheres, not just from LGBTIQ+ movement.

The campaign is not only opposing the law, it’s also trying to open people’s minds. It’s not limited to homo-, bi- or transphobia, but includes all sorts of discrimination. We want cis-hetero people to understand that we share common problems. We want to convey that the persecution of the LGBTIQ+ community is just the beginning, other social groups will follow.

What were the defined objectives and tactics of the campaign?

Initially, our objective was of course to prevent the new law from being passed.

We continued our lobbying activities, specifically targeting those MPs who might be persuaded to vote against the law. We started with a letter-writing campaign targeting MPs, which had proved to be a successful tactic in 2020. We also produced video messages from opinion leaders and organised public statements from committees, associations, organisations.

Video with English subtitles

We decided that our new objective should be the following: ‘to mitigate the damage of the new law and to consolidate and support the community’, so we started to publish articles, organise support groups and webinars with lawyers and psychologists on how to live in this new reality with this new law. We wanted to show that life is not finished.

Additional activities were targeted at people who could be referred to as ‘neutral’. They were not active allies, but were not queerphobic either. For them we had a different message because they had a different reason to be against this law. The focus with this target audience was not on LGBTIQ+ issues but on human rights in general, on the how the law would slow down progress, etc. These people were invited to send messages to MPs asking them to block the law.

Public activities like offline actions in different cities or online flashmobs with avatars on social media platforms were carried out partly by the “central” campaign team and partly by individual organisations.

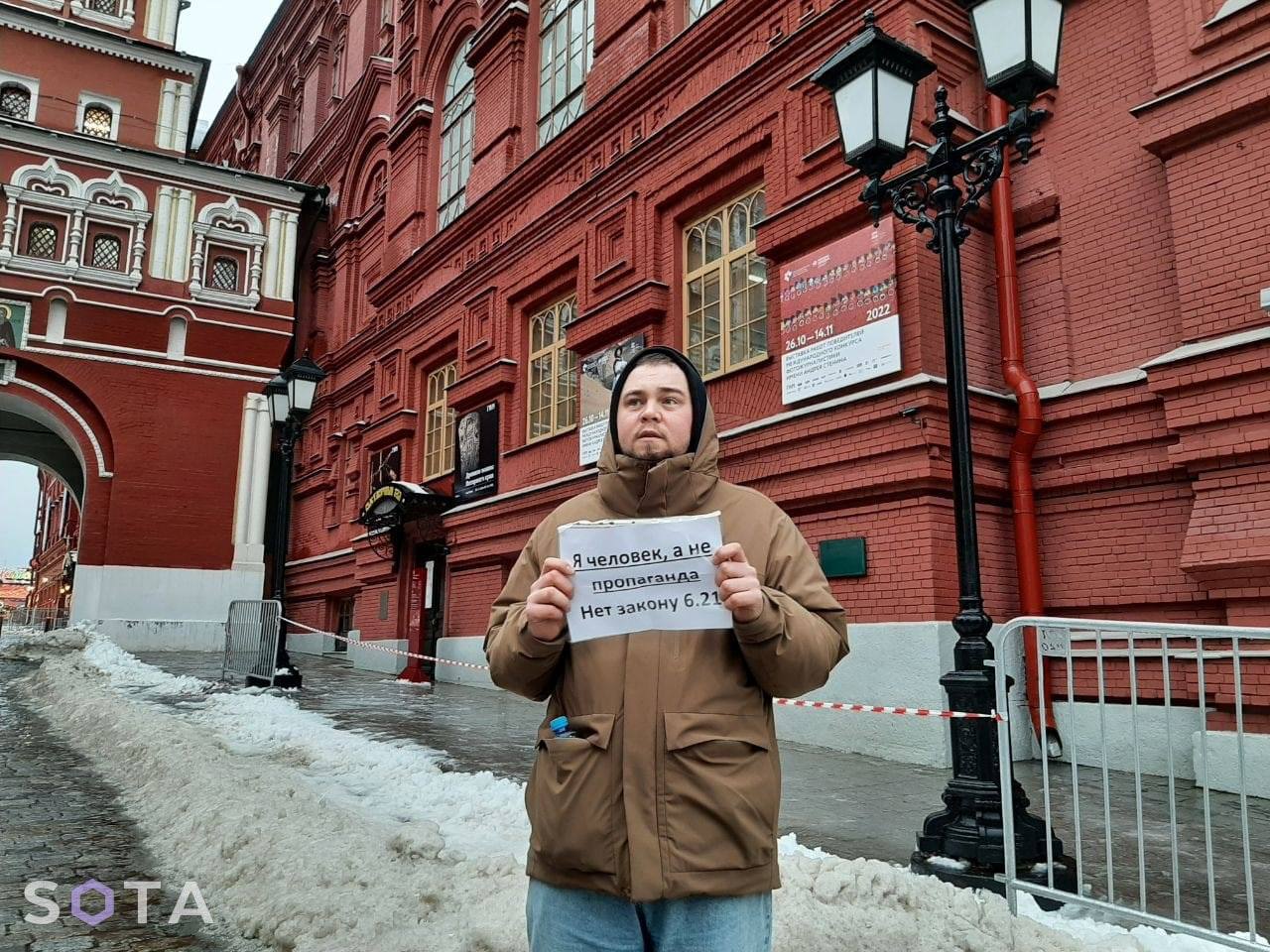

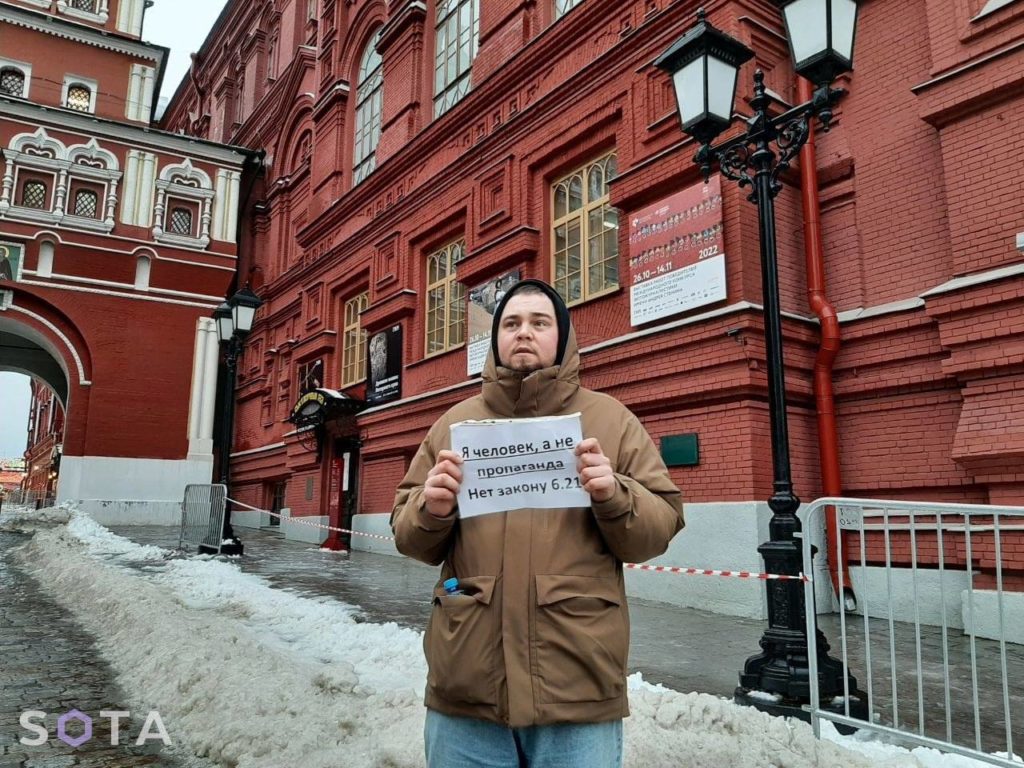

Protest: posters carrying the claim: I am a person, not propaganda. No to the law 6.21.

Protest: posters carrying the claim: I am a person, not propaganda. No to the law 6.21.

Dissemination of campaign material is often a challenge. How did you manage it?

We used a variety of channels over several months.

We mostly shared information through the and through the networks and channels of organisations and people who were part of our coalition. This ensured a wide outreach. It was important for us to use different platforms to make sure we reached various social groups with our message. We even shared information about the campaign in social media groups not related to activism, where we knew that audiences had quite negative attitudes towards activism in general.

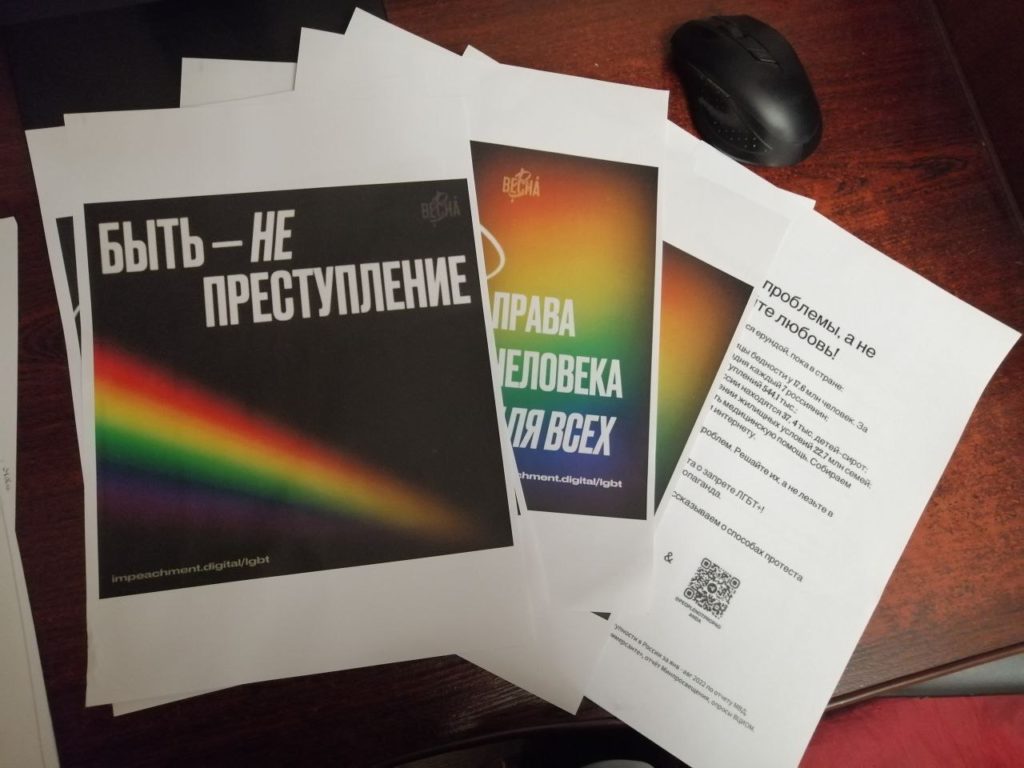

A range of information leaflets. Coloured ones stating ‘To be is NOT a crime; Human rights are for everybody’. These leaflets were distributed in Kaliningrad

We also launched a telegram channel where all the information and news related to the campaign and updates regarding the law was posted. We chose telegram as the most accessible and secure medium for Russian residents. A unique trait of our communication in our telegram channel was that we started creating memes, and they went viral.

Left button: Solve problems of inflation, unemployment, poverty. Right button: Ban books about people loving each other.

Left button: Solve problems of inflation, unemployment, poverty. Right button: Ban books about people loving each other.

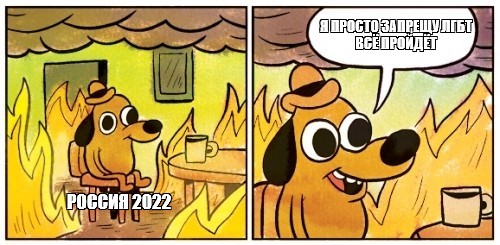

Left half: Russia 2022. Right half: Ban LGBTIQ+ people, and everything will be ok.

Top: 200 000 cases are already open; we are waiting for a million more. Bottom: Gosh, what have we done? We don’t have enough staff, who’s going to sort this out?

We worked directly with allies who helped us reach the ‘neutral’ people, such as the Youth Rights Committee, associations of people of faith, etc. We contacted them directly, explained our objectives, offered help with writing letters or petitions. We also contacted film distributors and publishing houses, because the law affects them directly.

We worked with opinion leaders and influencers: LGBTIQ+ bloggers, allies, activists in other spheres (feminists, eco-activists, etc.). We asked them to support our campaign by sharing information about it on their channels and encouraging their followers to join us. In this way we tried to spread information about our campaign beyond the information bubble of LGBTIQ+ organisations.

We launched a chat-bot through which people could share their stories, send feedback about their actions and reactions to letters they had sent, ask questions and offer partnerships.

How was the media coverage?

Of course, we knew that only so-called ‘oppositional’ and ‘liberal’ media outlets would provide positive coverage of the campaign, but we were surprised that there was so little coverage of the law by the pro-government media meaning that the campaign against the law didn’t attract much attention (even negative) either.

How do you see the result(s) of the campaign?

The campaign is still ongoing, so it’s difficult to talk about results. The initial goal – to prevent the Duma from passing the law – was not met.

Our current goal is to mitigate the consequences of the law by providing support, and we can already see results as people prosecuted under the law have sought help from LGBTIQ+ organisations.

A positive outcome is that people shared their stories. Even non-LGBTIQ+ people shared stories about their friends and relatives. It was very touching!

Another outcome is that non-activists became more aware of existing LGBTIQ+ organisations where they could come to seek help or just meet friends. As a result, a lot of people got involved and a cohort of “new” activists emerged.

Can you share some of the lessons you and your team have learned from this campaign?

When you work as a partnership, it is important not to underestimate the desire of some people and organisations to be the centre of attention. We had to manage tensions about our original intention to have an unbranded campaign and the desire for visibility from some groups.

You should also be prepared to accept that people and organisations who present themselves as allies won’t necessarily support your campaign.

The main positive lesson we learned is that it is possible to review goals and priorities while you are planning your campaign.

It was a new experience for all of us, but we’re glad we did it. If we had not changed the objective of the campaign, we would not have had such a positive result, resulting in disappointment. We reassessed our approach and made our campaign more efficient.