What does “Campaigning” really mean?

How Plato can help us redefine campaigning

We all know that campaigning has been going through a bit of a rough patch, with the lobbying act and all. However, I was still taken aback when someone referred to campaigning as the “C” word. A little strong, maybe. However, as I go round the country talking to people as part of the foundation’s Social Change Project, it becomes increasingly clear just how much of a problem language can be.

A woman in Manchester, who has an incredible track record of combating gun crime in her community, says she didn’t know what to call herself for a long time. She resisted the tag “community activist” because it made her sound angry and confrontational, and she isn’t. In fact, she is a highly sophisticated change-maker.

Another woman, this time in the Midlands, leads a charity for vulnerable adults. She doesn’t recognise the term “campaigning” because she understands it to connote challenging power from the outside. She works closely with her local authority – a relationship not without its trials – but she is on both the inside and the outside. She is, if anything, a negotiator.

The people who seem most comfortable with the term “campaigner” are those who work in professional roles for charities. They like the term and want to own it. Their gripe is that their organisations don’t understand campaigning and don’t give them the permission and space they need.

The Social Change Project has an ambition to detoxify the language around campaigning: to “reframe” the word, if you will, and consider new terminology and positioning that can make all parties feel more comfortable with campaigning and able to support it. Few would argue that people shouldn’t have voice and agency, and be able to shape their world. But what can we call this important endeavour?

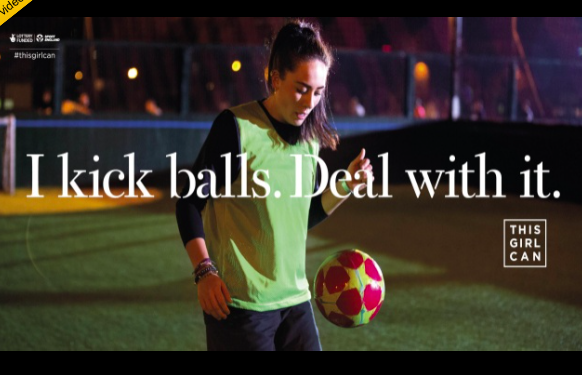

Our early conclusion is that terms such as “activist” and “campaigner’” seem too oppositional and confrontational: spirited but unsophisticated. Meanwhile, being a “social entrepreneur” or “innovator” feels too passive politically, too commercial. Do we go for the neutral territory of “change-agent” or “change-maker”? Does anyone really use such language or know what it means? And sometimes campaigning isn’t about change. Sometimes campaigners are trying to maintain the status quo. Think Remain.

I was pondering this with a friend, who came up a nice idea. Campaigners should think of themselves as modern philosophers, he proposed, in line with the model of philosopher kings in Plato’s Republic. Plato believed political office should be held by philosophers, who are defined as having knowledge, not power, and whose role it is to ask questions in pursuit of what is good. I like it: rather than thinking of campaigning as speaking truth to power or pursuing change, we should think of it as being about asking questions.

Recognising that change is about us all the time, our job is to ask “is this change good, right and fair?” Of course, this will entail holding those with power to account, but it moves the core purpose of campaigning upstream. We are not pursuing change or opposing things for the sake of it. We’re not just angry people. We are asking questions in the interests of making society better. And what on earth can be wrong with that?