Is humanity controlled by alien lizards? – how fake news and robots influence us from within our own social circles.

Is humanity controlled by alien lizards? – how fake news and robots influence us from within our own social circles.

Even these days, there are still 12% of Americans to believe humanity is controlled by alien lizards who took human shape. Replace “alien lizards” with “bots”, and the laughable conspiracy theory might not be that funny anymore.

Increasingly all social debates and political elections are manipulated by social bots and the most worrying news is that opponents to a cause or a party manipulate supporters of this cause or party from within their own social circles. We must absolutely understand how this is working against our social struggles, if we are to keep control of our campaigning strategies.

One of the most verified truth of campaigning is that people only get really influenced by attitudes and behaviors of other members of their social circles, as the conformity bias drives most of us to follow what we perceive our fellows think and do.

And where do these patterns appear more clearly than on social media? Clicks, likes and comments drive most of us to distinguish what is appropriate from what is not.

Political strategist have been constantly researching how to make the most of this and use individuals as one of their main channels to propagate their ideas.

In recent years the explosion of the use of social bots, allied to a shameless use of fake news, have given the strategists the most worrying tools to influence attitudes and behaviors, including our own.

The increasing presence of bots in social and political discussions

Social (ro)bots are software-controlled accounts that artificially generate content and establish interactions with non-robots. They seek to imitate human behavior and to pass as such in order to interfere in spontaneous debates and create forged discussions.

Strategist behind the bots create fake news and fake opinions. They then disseminate these via millions of messages sent via social media platforms.

With this type of manipulation, robots create the false sense of broad political support for a certain proposal, idea or public figure. These massive communication flows modify the direction of public policies, interfere with the stock market, spread rumors, false news and conspiracy theories and generate misinformation.

In all social debates, it is now becoming common to observe the orchestrated use of robot networks (botnets) to generate a movement at a given moment, manipulating trending topics and the debate in general. Their presence has been evidenced in all recent major political confrontations, from Brexit to the US elections and, very recently, the Brazilian elections:

On October 17, the daily Folha de S. Paulo, revealed that four services specialized in the sending of messages in mass on WhatsApp (Quick Mobile, Yacows, Croc Services, SMS Market) had signed contracts of several millions of dollars with companies supporting Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign.

According to the revelations, the 4 companies have sent hundreds of millions of messages on large lists of whatsapp accounts, which they collected via cellphone companies or other channels.

What these artificial flows represent in terms of proportion is frightening.

According to a Brazilian study, led by Getúlio Vargas Foundation, which analyzed the discussions on Twitter during the TV debate in the Brazilian presidential election in 2014, 6.29 percent of the interactions on Twitter during the first round were made by social bots that were controlled by software that created a massification of posts to manipulate the discussion on social media. During the second round, the proliferation of social bots was even worse. Bots created 11 percent of the posts. During the 2017 general strike, more than 22% of the Twitter interactions between users in favor of the strike were triggered by this type of account.

The foundation conducted several more case studies, all with similar results.

Twitter is Bot land

Robots are easier to spread on Twitter than on Facebook for a variety of reasons. The Twitter text pattern (restricted number of characters) generates a communication limitation that facilitates the imitation of human action. In addition, using @ to mark users, even if they are not connected to their network account, allows robots to randomly mark real people to insert a factor that closely resembles human interactions.

Robots also take advantage of the fact that, generally, people lack critical thinking when following a profile on Twitter, and usually act reciprocally when they receive a new follower. Experiments show that on Facebook, where people tend to be a bit more careful about accepting new friends, 20% of real users accept friend requests indiscriminately, and 60% accept when they have at least one friend in common. In this way, robots add a large number of real people at the same time, follow real pages of famous people, and follow a large number of robots, so that they create mixed communities – including real and false profiles ( Ferrara et al., 2016)

How Whatsapp is trusting the debate in Brazil

But Twitter is not the only channel. All social media experience the same strategies of infiltration, depending on what is being used by the specific group targeted by unscrupulous strategists.

In most countries whatsapp is a media restricted to private communications amongst a close circle.

But in Brazil, it has largely replaced social media. Of 210 million brazilians, 120 million have an active Whatsapp account. In 2016, a . En 2016, Harvard Business Review study indicated that 96 % of Brazilians who has a smartphone used Whatsapp as prefered messaging app.

Although disseminating information is rather difficult, with Whatsapp groups being limited to 256 people, the influence of messages is extremely high as the levels of trust within Whatsapp groups are higher than anywhere else. So investing in reaching these groups turns out to be extremely effective.

Furthermore, regulation and traceability of fake news are extremely difficult as messages are encrypted.

As a result, some Brazilians have reported receiving up to 500 messages per day according to Agence France Presse

And the impact of this tactic is not to be underestimated: The internet watchdog Comprova created by over 50 journalists analysed that among the fifty most viral images within these groups, 56% of them propagate fake news or present misleading facts.

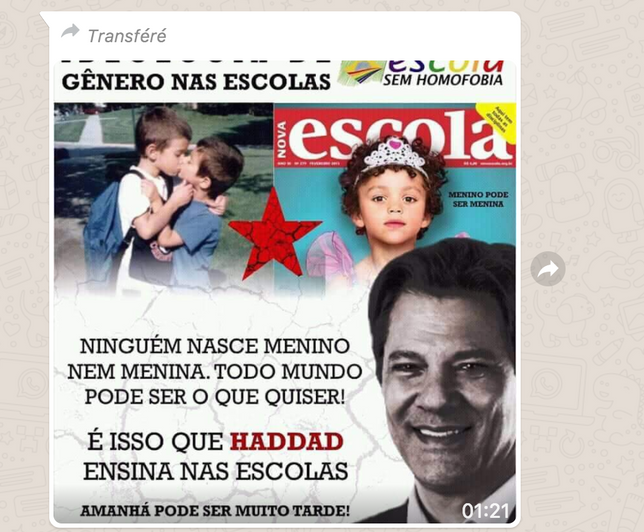

The “virality” of fake news is particularly strong in the case of images and memes, such as the one pretending that Fernando Haddad, the candidate of the PT, aimed at imposing “gay kits” in schools.

Not only is this highly immoral but, in the case of Brazil also illegal, as the law only allows a party to send message to its enrolled supporters. Not to speak of how this constitutes illegal funding of political campaigning.

Following the disclosure, Whatsapp closed 100 000 accounts that were linked to the 4 companies, but this represents only a fraction of the problem, and in any case the damage was done.

This manipulation is generated within supporters groups to discredit their opponents

In line with what has been happening since the beginnings of politics, influencers act within groups of supporters of a cause or a party to discredit their opponents and help tighten the group.

The same strategy is applied to target the moveable audiences and win them over.

In this respect, the major change that bots bring is the size and speed of the manipulation.

Attacking from within

But the worrying trend is that the army of fake news and opinion distortions also attack our movement from within.

The University of Washington released in October 2018 the results of investigationsin the social discussions during the 2016 US presidential elections that showed that many tweets sent from what seemed to be #BlackLivesMatter supporters were not posted by “real” #BlackLivesMatter but by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) in their influence campaign targeting the 2016 U.S. election. Of course, the same was true of #BlueLivesMatter.

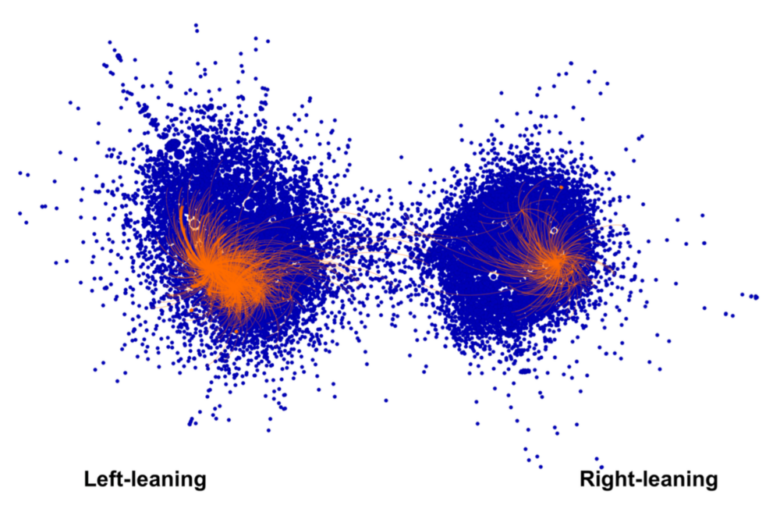

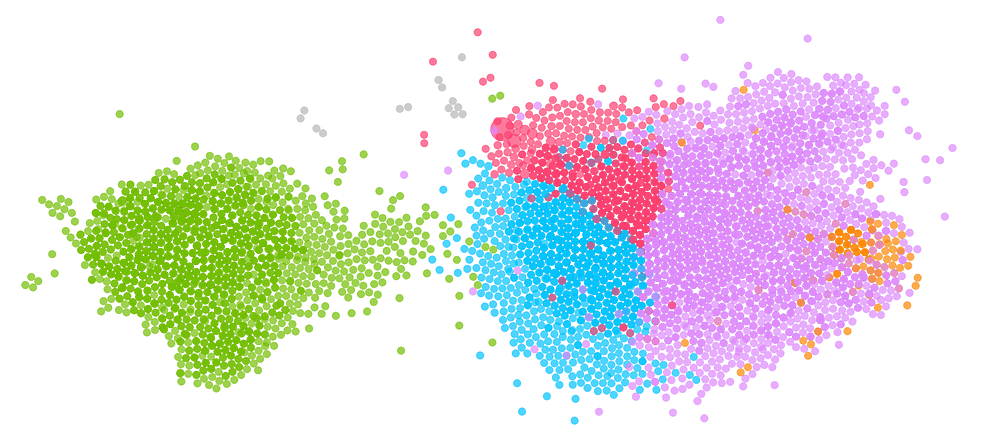

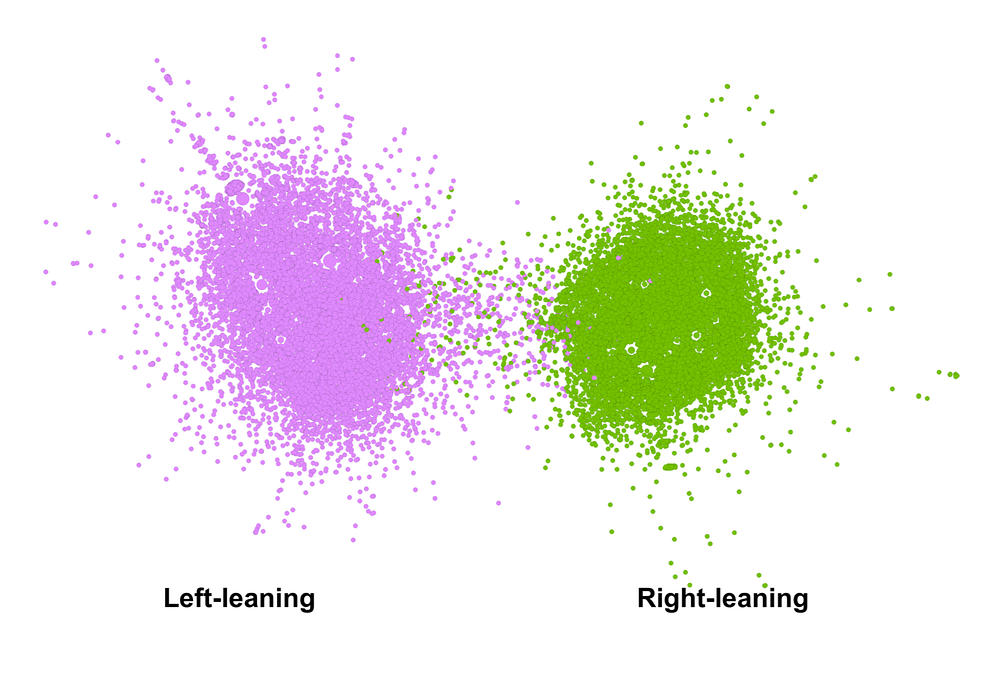

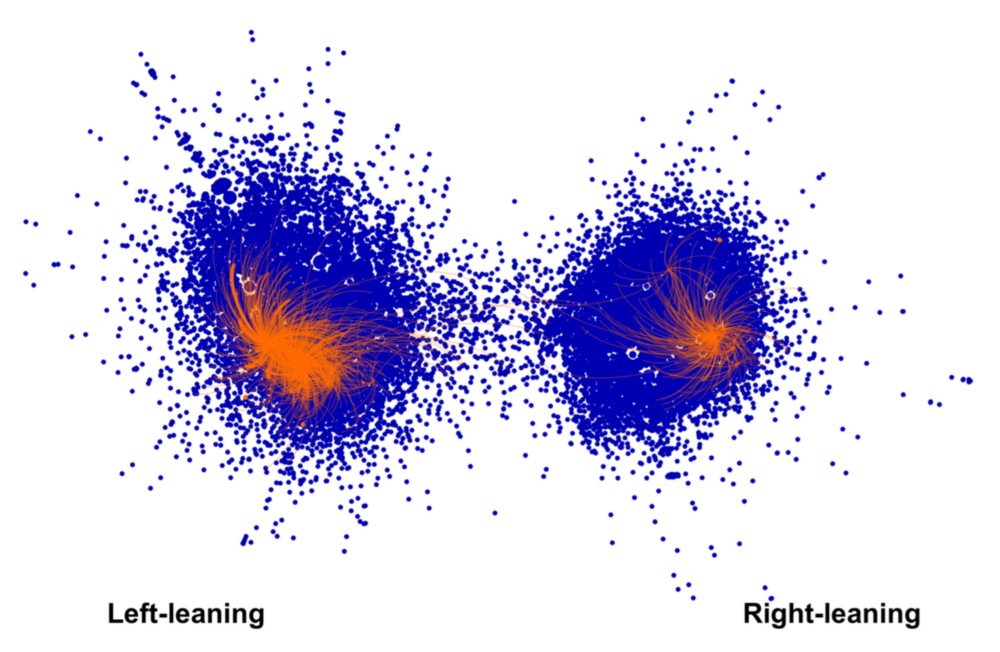

The creepy graph below shows in orange the IRA accounts, within the larger blue circles of pro and anti BLM conversations.

The IRA accounts impersonated activists on both sides of the conversation. On the left were IRA accounts that enacted the personas of African-American activists supporting #BlackLivesMatter. On the right were IRA accounts that pretended to be conservative U.S. citizens or political groups critical of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Infiltrating the BLM movement by increasing the presence of radical opinionswas a clear strategy to undermine electoral support for Hillary Clinton by encouraging BLM supporters not to vote.

Outrageous fake news that come from our opponents are relatively easy to spot and dismiss, but when more subtle fake news and artificial massification of opinion use our own frames and come from what seem to be elements of our own movements, the danger is much bigger.

What does this mean for SOGI campaigning?

Political pressure on social media to reinforce regulations is mounting from governments and multilateral institutions such as the EU.

Issues of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, and sex characteristics are almost always used by conservatives to discredit progressives and whip up moral panics.

Supporting institutional efforts to control fake news would probably always work in our favor.

More and more public and private initiatives are being developed to bust fake profiles.

For example, Brazil developed PegaBot, a software that estimates the probability of a profile being a social bot (e.g. profiles that post more than once per second).

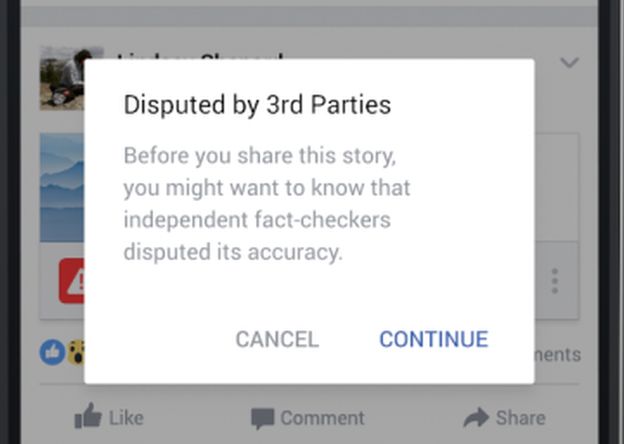

TheBBC reportsthat through the International Fact Checking Network (IFCN), a branch of the Florida-based journalism think tank Poynter, facebook users in the US and Germany can now flag articles they think are deliberately false, these will then go to third-party fact checkers signed up with the IFCN.

Those fact checkers come from media organisations like the Washington Post and websites such as the urban legend debunking site Snopes.com. The third-party fact checkers, says IFCN director Alexios Mantzarlis “look at the stories that users have flagged as fake and if they fact check them and tag them as false, these stories then get a disputed tag that stays with them across the social network. “Another warning appears if users try to share the story, although Facebook doesn’t prevent such sharing or delete the fake news story. The “fake” tag will however negatively impact the story’s score in Facebook’s algorithm, meaning that fewer people will see it pop up in their news feeds.

The opposite could also be favored, with « fact-checked » labels being issued by certified sources and given priority by social media algorithms.

Of course, this would create strong concerns over who would hold the « truth label » and how this would play out to silence voices which are not within the ruling systems.

But beyond these and other initiatives to get the social media platforms to exert control, campaign organisations also need to take direct action.

As a systematic step, educating our own social circles on fake news and bots now seems unavoidable.

We might even need to disseminate internal information to our readers, membership or followers, warning them of possible infiltration of the debates by fake profiles that look radical. But this might also lead to discredit the real radical thinking which we desperately need.

One of the most useful activities could be to increase our presence in other social circles and help these circles identify and combat fake news. Some people are so entrenched in their hatred that they will believe almost anything that will justify their hatred. But most people are genuinely looking for true information. After all, no one likes to be lied at and manipulated. If we keep identifying and exposing fake news within the social circles of these moderate people, we can surely achieve something, at least help block specific profiles by reporting them.

The net is ablaze with discussions on how to counter the manipulation of public opinion by bots. As one of the first victims of this, we surely must have our part to play.