Six behavioural psychology tips for effective campaigns

Changing people’s behaviour is difficult. If we want people to take sustained action in support of international development issues, we need to understand behavioural psychology and build this into our campaign design.

A recent CharityComms conference on developing behaviour change campaigns made me think about what lessons the development sector could learn from organisations like Sport England and the RNLI. These charities root their campaign strategies in an understanding of psychology in order to change the behaviour of their target audience.

1. Get to know your audience

In-depth audience knowledge is vital for a successful campaign. We talk about this a lot. But how well do we really know the audience we’re trying to reach? Where do they live? How old are they? How do they spend their free time? What are their main concerns? Where do they get their news? Who do they trust?

For example, Sport England spent time preparing the ground for their successful This Girl Can campaign by first listening to, then engaging in conversation with, women online.

One of the lessons of the EU referendum is that organisations need to be more in touch with their audiences. To be successful campaigners, we need to get out and about and talk to people we don’t usually come into contact with about their concerns. We need to step out of our comfort zone and try new ways of communicating and collecting information.

Sheffield-based social enterprise Aid Works is a good example of an organisation talking to a diverse range of people. They work all over Yorkshire, holding community meetings and going into schools.

2. Normalise the action

People are herd animals; we are strongly influenced by what those around us are doing. Given the option between two unfamiliar restaurants, one empty and one busy, most of us would choose the busy restaurant. We assume the food is better because everyone else is eating there.

If we want people to take action on international development issues, we need to show our audiences that the desired behaviour is “normal”.

We also need to be careful not to promote the opposite behaviour in our communications. For example, communicating that “134 patients failed to attend their appointments last month” in a doctor’s surgery, reinforces the idea that lots of people are missing appointments and won’t encourage the desired behaviour. The surgery would be better saying: “99% of patients kept to their appointments last month, make sure you do too.”

3. Choose the right messenger

We are also heavily influenced by the person communicating information to us. Social enterprise Behaviour Change explain that there are two important factors which determine the success of a messenger: whether or not they have experience of the issue and whether the audience trusts them. Insight from the Aid Attitude Tracker (AAT) backs this up. AAT research shows that the best messengers for development issues are ones whom the audience perceives to be both warm and competent.

Of course, to choose the right messenger you need to understand your target audience. In order to influence behaviour change in commercial fishermen, a closed network with a strong identity, the RNLI chose to work through partners like the Fishermen’s Mission and found individual fishermen that the community trusted to spread their message.

4. Appeal to the subconscious

Human behaviour is influenced by subconscious cues, as much as – if not more than – by our conscious thoughts.

This is why, for example, food retailers often pump out a signature scent. It serves as an aromatic marketing poster, triggering memories and desires, which encourage an emotional connection with the product.

Perhaps bringing a signature scent into international development campaigning is a little far-fetched, but exposure to certain words, colours and images can also have a subconscious effect on our behaviour.

Putting a mirror behind one tray of pastries at the CharityComms conference meant that fewer pastries were eaten from that tray, because people subconsciously self-evaluated before adding them to their plate. The colour blue is associated with trust and honesty and could be used to subconsciously impart such feelings to an audience when used in a presentation.

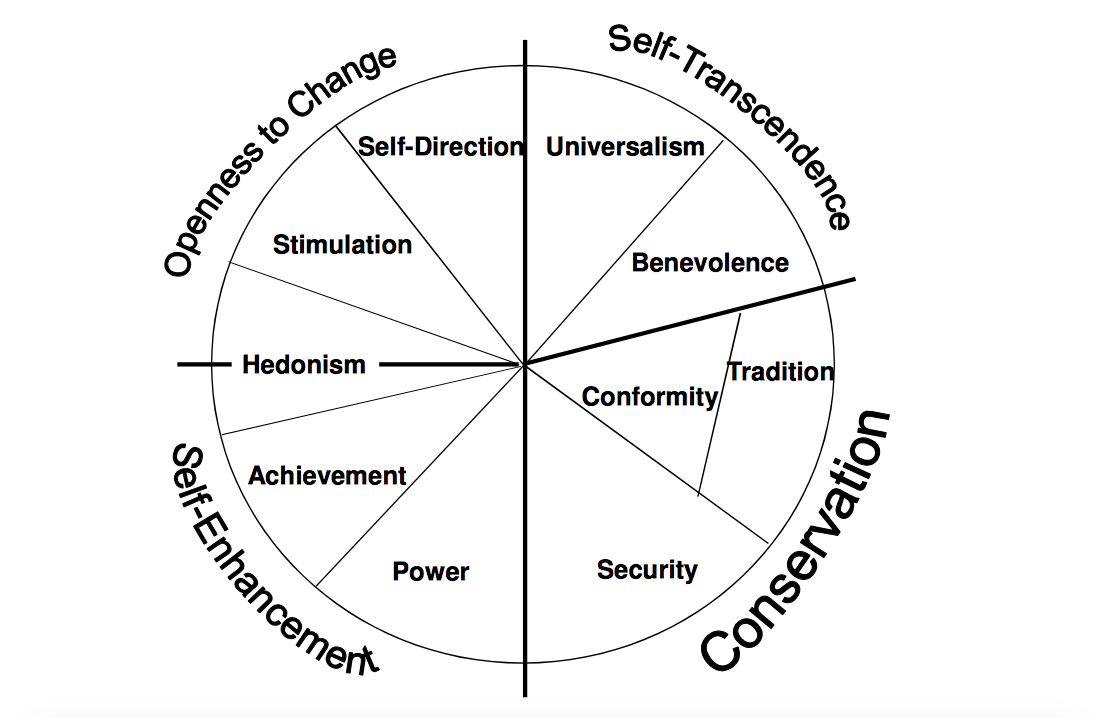

5. Strengthen intrinsic values

Psychologists have identified a number of consistently occurring human values: the things that people say they value in their lives. The prevalence of these values has been tested many times and found to be consistent across different countries and cultures. They can be grouped broadly into intrinsic and extrinsic values. The Common Cause Foundation explains more.

Extrinsic values are centred on external approval or rewards, for example: wealth, image, social status and authority. Intrinsic values relate to things we find inherently rewarding, for example, self-acceptance, connection to family and friends, connection with nature, and concern for others.

How can international development campaigners make sure we are designing campaigns that promote intrinsic values rather than extrinsic values?

Global Action Plan, a charity inspiring people to take practical environmental action, promote the values important for sustainable development through their work with school children. They found that pupils were more likely to adopt those values if they practised them through activities in the Water Explorer programme, instead of simply being told about them. We need to find ways to apply similar techniques to campaigns targeting adults.

6. Use a multi-dimensional approach

Behaviour change campaigns need to be multi-dimensional. And all the different elements need to work together. National, public-facing communications; face-to-face work with the target audience at a local level; and products which make it easy for people to change their behaviour all need to complement each other to have maximum impact.

For example, Parkinson’s UK combined national communications and work with in-house trainers in the retail and transport sectors, to promote understanding of Parkinson’s disease and other “hidden disabilities”. The Time to Change campaign addressed their audience of 25 to 44-year-olds across England through national, local and individual strategies to tackle mental health discrimination.

When designing and developing a behaviour change campaign, it is also important to bring in different opinions: expert and non-expert. Gathering a group of people with different expertise and different perspectives will help to create a campaign with a much broader appeal.

Have you seen any examples of campaigns that use behavioural psychology effectively? Have you tried any of these techniques in your own campaigns? Tweet us @bondngo with your ideas and suggestions.