In Russia, an organisation of Trans people got itself prepared for when the foreseeable gag law was voted. This interview bring you backstage.

On 5 December 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin signed a new law that prohibits “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations and pedophilia.”

On the very same day, the biggest Russian trans-group launched its online campaign “No Words”.

Anton Macintosh, a member of the group, tells us all about it.

What kind of context was your organization working in when the campaign started?

Our organization has been running since 2014. We have been providing various types of support for the trans community offline and through media, as well as educational projects for helping professionals.

Coinciding with the “propaganda” law, we were declared a foreign agent and as a result we had to close down but of course we wanted to continue our activities so we immediately reformed a new entity which had to circumnavigate these restrictions.

How did you achieve this “mission impossible”?

The objectives and activities of the new organization were exactly the same, but directly to a population of ‘kilkots’. Kilkot is a well-known mascot to our organisation and its allies, half-cat, half fish, a kind of cat-mermaid. In our new social media accounts we write the same things as before, but instead of transgender issues we talk about “kilkot issues”. It would be very interesting to see if the authorities could forbid us to talk about “Kilkots”!

How was the idea of the “No words” campaign born?

The old ‘anti-propaganda’ law was about not letting minors know about LGBT+ but it didn’t prohibit being LGBT+ or raising these topics. The new law is different. It prohibits ‘forming a positive image’ or ‘speaking about the justification of transitioning’ in general, regardless of the audience. So it basically criminalises mentioning these subjects in a positive way at all.

In the face of this “gagging” of our community, we wanted to be proactive and give the community members the opportunity to express themselves at the very moment when the law was passed.

We chose the title No Words because it has a double meaning. On the one hand, it’s the direct reflection of the new law – that no words are allowed to talk about ourselves. And on the other hand, ‘no words’ (net slov) is the Russian equivalent of “at loss for words”, that people use when they are shocked and they literally have no words to describe their emotions.

What is this campaign exactly?

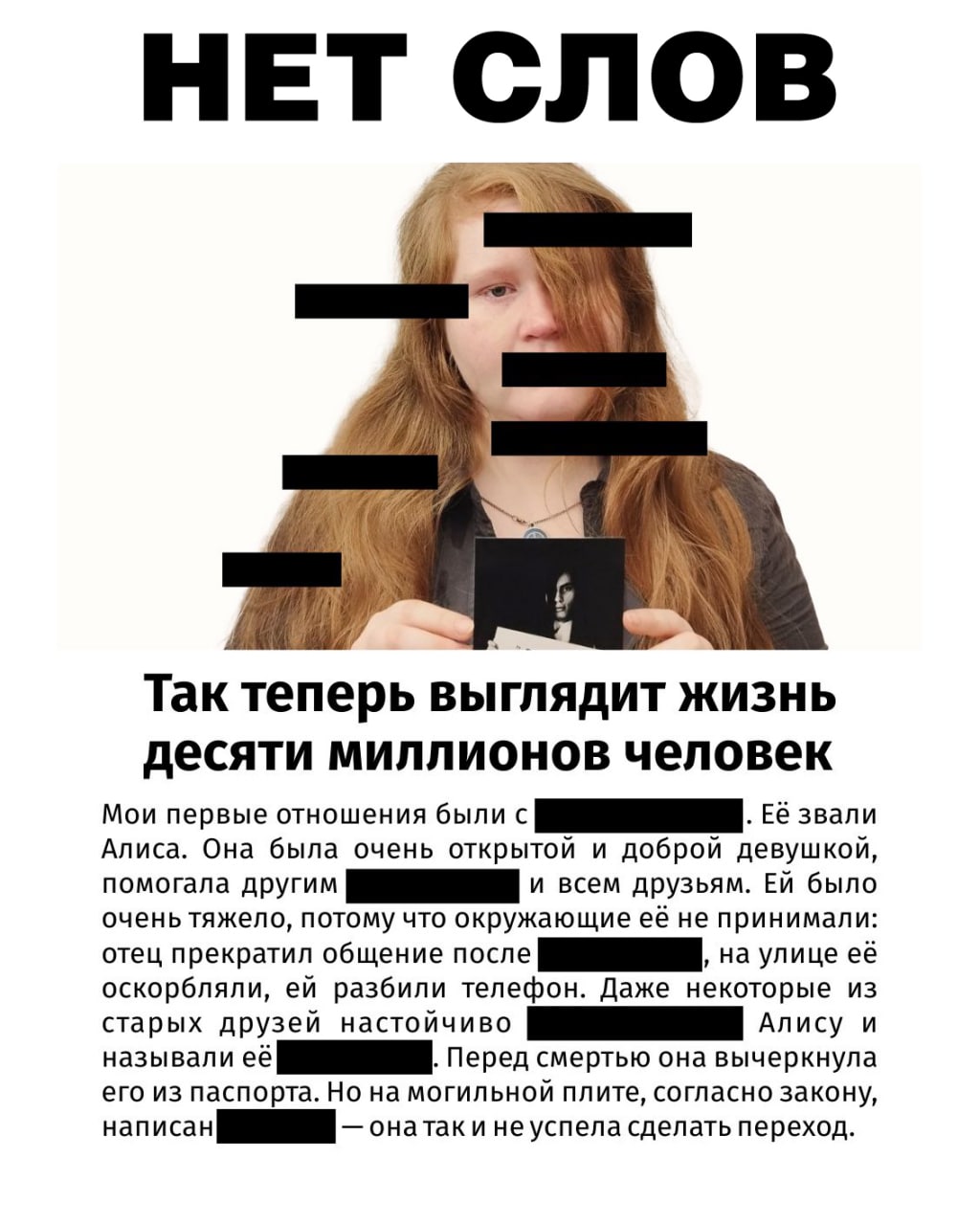

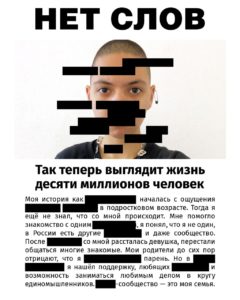

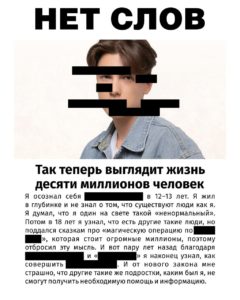

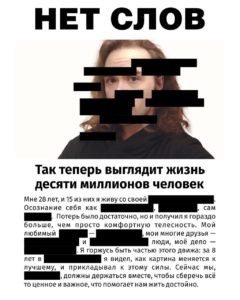

The main objective is literally to show what people’s lives look like now. To show that it’s not just a ban on covering certain topics in the media – it’s literally crossing out lives of trans people and all of LGBTIQ+ people in general.

By covering the words deemed “illegal” in Russia in people’s stories with these black markers, we show how much of people’s lives are being erased. The main message is the headline of each poster : “This is what the life of 10 million people looks like now”. Since there is no official statistical data, we did our own maths.

Covering up parts of their faces too underlines that erasing people’s stories is to erase them altogether.

The tactic is to turn the opponents’ logic against them: We are using the law that seeks to invisibilise us as an opportunity for becoming more visible!

Who is the target audience of the campaign?

Our primary target audience are trans people as they are the most vulnerable ones because they are dependent on the State – they need permanent gender affirmative medical care, and depend on the State for their legal gender recognition.

Since February 2022, we have been surveying the needs and the wellbeing of the community every three months. So we knew exactly how the trans community was feeling when the law was passed. And while discussing the idea of the campaign and thinking of what might be most beneficial for them in this situation, we took the results of these surveys into consideration.

At the same time, this campaign was also meant to address the wider society, which we had never done before in such a strategic manner. Mind you, we are not talking about all of society, but mainly about the audience of liberal media, the so-called movable middle.

Initially, you published stories of trans people, but then you also started to publish stories of any LGBT+ people. Why did you decide to expand the scope of the audience?

We did it because people started sending us stories. Initially we invited trans people to share their stories with us and with everyone. But we realized that not only trans people were submitting their stories. We could not refuse to publish these stories. We are not Roskomnadzor, the Russian State’s Communication Authority, we don’t do censorship.

Is there any selection process for the stories? Any criteria?

We publish all the stories we receive through a special form, but in this form there are specific criteria which people should follow. Like, for example, there’s a certain length they cannot exceed. Also, they must mention their gender identity and/or sexual orientation.

Surprisingly enough, there were a couple of stories with no words to cross out. Apparently, people quickly adapted to these new laws and did an act of self-censorship. Obviously, we could not publish these stories, because there was no point.

Dissemination of LGBT campaign material in Russia is often a challenge. How was it for you?

We had prepared a press-release that was ready to be released when the law would pass. We sent it to various bloggers and media outlets, and all the friendly liberal ones published it almost instantly. The press-release contained the first nine stories that we had prepared in advance. And after the news about the campaign was published, people started sending us their stories.

Actually, when the Russian authorities published their criteria for ‘propaganda’, which is outrageously restrictive, it provoked a second wave of indignation and fear in the community and so we launched the second phase of our campaign to help people release these emotions.

All of the stories people have sent us are published here.

This campaign was prepared with the help of Linor Goralik, a very famous poet and writer. It is an important precedent for an LGBT+ group in Russia to get support from a celebrity of such a level. Can you tell us how this all came about?

Linor Goralik is a world-famous marketing analyst, writer and comics illustrator. I met her during an online marketing course for NGOs in Autumn 2022.

I contacted her and asked her to help us design the campaign and she agreed. This law is so awful and it obviously affects not only trans people, not only LGBT+ people, but everyone.

She helped us from the very beginning, especially with the question of promoting our campaign. We sought her help because she’s an expert in promoting low-budget campaigns in the NGO sphere.

She helped design the whole campaign. As a marketing specialist, she worked with us on looking for and finding the idea, the slogan, and everything else. So basically, without her this campaign would not have happened or would not have been as it is.

The campaign is still ongoing, but can we already talk about how you see the impact of the campaign?

Another positive result is the expressions of gratitude from the community members for this opportunity to express themselves. There were a lot of these in the comment sections on our social media.

It’s too early to measure the overall impact of the campaign on the target audience, because it’s still ongoing, but we can already see some shift in rhetoric in the general public. More people, especially allies, started to express their support in the comments and PMs, or to come to our events. People who had not expressed their support for the trans community before came out and did so.

We received a lot of support, not just in words but people started asking how they can support us financially, and we received a lot of donations. It was quite unexpected and it was the first noticeable effect of the campaign.

One more important result of this campaign is that our course for psychologists, sexologists, psychiatrists and other mental health specialists on how to work with Trans people has received twice as many applications as before the adoption of the law!

Also, there’s a huge increase in followers on our social media and in volunteers.

Has there been any backlash?

As for the negative consequences, our campaign was targeted by some alt-right communities, but there were no major public actions. This exposure just got us more followers, which is good, right?

We also got some negative feedback from inside the community regarding the idea of these black bands. Their argument is that we had given in to censorship and that we should have resisted the law and published the full stories. But that would have meant leaving Russia which is not what we intend to do.

A concluding remark?

To conclude, I’d like to say that with this campaign we have certainly achieved two things: we have given voice to the people from our community and we have tested the language that we can use to talk with and about the community while staying here in Russia.