From New York Times, a must-read article on canvassing approaches.

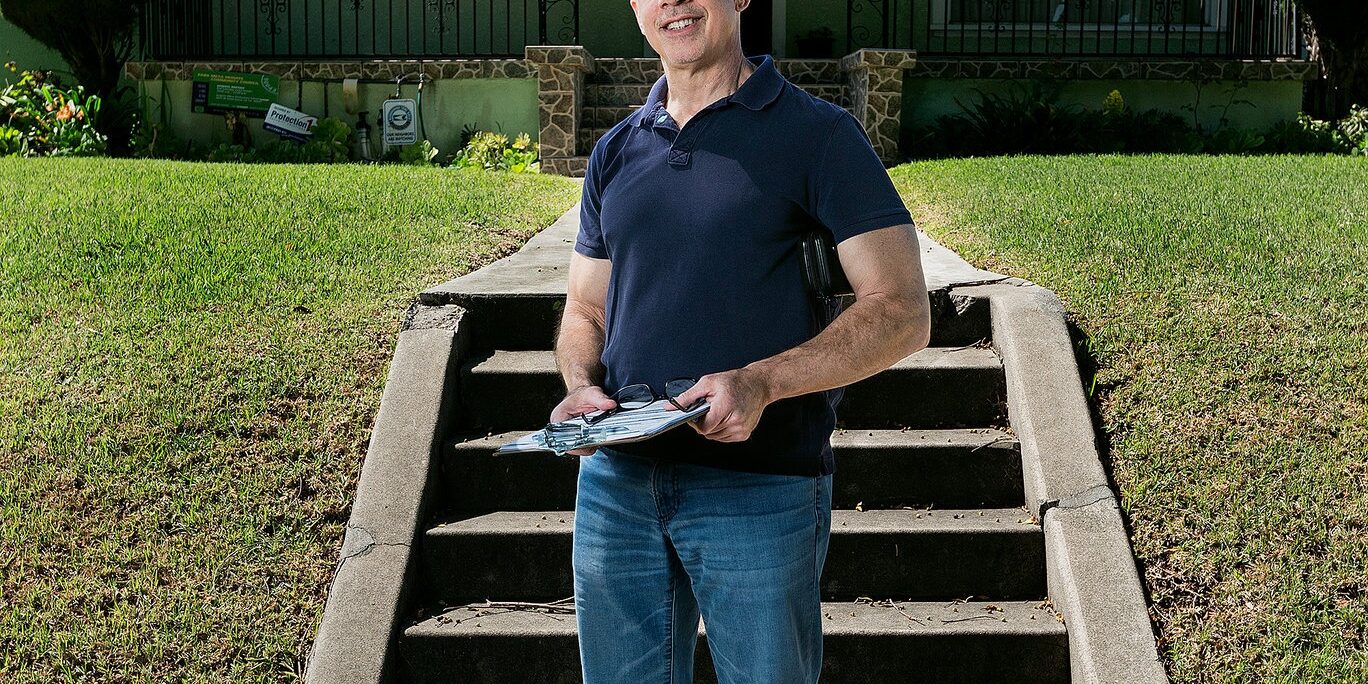

Dave Fleischer — a short, bald, gay, Jewish 61-year-old with bulging biceps and a distaste for prejudice — knocked on the front door of a modest home in a middle-class neighborhood on the west side of Los Angeles. It was an enthusiastic knuckle-thump, the kind that arouses suspicion from dogs in yards halfway down the block but, crucially, can also be heard by humans watching cable news at high volume.

If he had his way, Fleischer would knock on doors with a golf ball. “That’s what the Mormons use,” he said on this sunny, bird-chirping Saturday in February. Fleischer’s staff at the Los Angeles-based Leadership Lab — which goes door to door to reduce bias against L.G.B.T. people, with a current focus on transgender discrimination — didn’t take to the golf-ball suggestion, but Fleischer wanted me to know that he is “not opposed to stealing a good idea from the Mormons.”

A gray-haired Hispanic woman named Nancy cracked open the front door, though not enough to let her little dog eat our ankles. “We’re out talking to voters about an important issue — ” Fleischer began, only to have Nancy excuse herself and walk away. I wasn’t sure she would return; the last two voters he’d met pleaded busyness. But after shooing the dog into another room, Nancy appeared in her doorway again. She smiled shyly and asked Fleischer, the Leadership Lab’s director, how she could help him. Had he been completely honest, he might have said, “I’m here to make you less prejudiced. It could take awhile.” But instead he began with a simple question: If she were to vote on whether to “include gay and transgender people in nondiscrimination laws,” would she be in favor or opposed?

“In favor,” she assured him. Fleischer asked her to rate that support on a scale from zero to 10. “A 10,” she said. “I have friends who are gay.”

A typical canvassing conversation might have ended there. Nancy, it seemed, was a supporter — no need to worry about her. But Fleischer is wary of what he calls the “anti-discrimination declaration.” At the Leadership Lab’s two-hour pre-canvass training that morning, volunteers were warned about “fake 10s,” people who think of themselves as against discrimination — many of them Democrats — but who can nonetheless be swayed by emotion-based appeals that provoke prejudice and fear.

At the door, Fleischer asked Nancy if she knew any transgender people. She didn’t. He then did something few political consultants would advise: He introduced her to the opposition’s favorite argument. He handed her a small video player, on which she watched a Baptist minister in Houston make the case about bathrooms. Fleischer then returned to his scale, asking Nancy what number felt right for her now. “I know I’m in favor of gays, because I’ve worked with them and socialized with them,” she said. “I think they’re wonderful. But for transgenders? Give me a five.”

Nancy wasn’t the only person to significantly decrease her support after watching the video. Across the street, a man in his late 30s who said he was liberal and pro-L.G.B.T.-rights moved to a five from an eight, explaining that he was deeply worried about “the bathroom issue.” The man’s concern seemed informed by his experience in a New York City nightclub; he hinted at his discomfort standing at a urinal next to a drag queen. Nancy had no such seemingly relevant personal experiences, nor did she appear particularly concerned about bathroom safety. For her, the video seemed to clarify that Fleischer was specifically asking her about transgender people, a group she had no experience with and seemed to have little inherent empathy for. To get Nancy to a true 10 capable of withstanding opposition messaging, Fleischer needed to help her “tap into her own empathy and connect emotionally to transgender people.”

Fanned out across the neighborhood were more than three dozen Leadership Lab volunteers, many of them local college students, as well as progressive activists from around the country hoping to learn about changing voters’ minds. Over the last six years, Fleischer’s unorthodox canvassing technique has attracted the attention of social scientists, liberal groups and even presidential-campaign consultants. It has also attracted controversy. In 2014, Science published a study claiming to show that an approximately 20-minute conversation with a gay or lesbian canvasser trained by Fleischer’s team could turn a gay-marriage opponent into a supporter. But Science retracted the study five months later, after the lead author couldn’t produce his data and admitted to lying about aspects of the experiment’s design.

The fraudulent study called into question the validity of the Leadership Lab’s deep-canvassing approach. Had it all been wishful thinking? Maybe, as The Wall Street Journal suggested, Fleischer’s efforts merely “flattered the ideological sensibilities of liberals.” But this week, a new study published in Science by David Broockman, an assistant professor of political economy at Stanford, and Joshua Kalla, a graduate student in political science at Berkeley, appears to serve as vindication of Fleischer’s work. Leadership Lab-trained volunteers were found to be successful at reducing transgender prejudice in front-door conversations, the effects persisting months later in follow-up surveys.

Betsy Levy Paluck, an associate professor at Princeton who studies bias, believes the study will have broad implications for those in her field. “What do social scientists know about reducing prejudice in the world? In short, very little,” she writes in the same issue of Science, adding that the new study’s results “stand alone as a rigorous test of this type of prejudice-reduction intervention.”

Fleischer is planning more interventions. Though he has devoted much of his political and community-organizing career to L.G.B.T. issues, he believes this kind of canvassing could change people’s thinking on everything from abortion and gun rights to race-based prejudice. He also hopes it will usher in a new era of political persuasion. “Modern political campaigns have focused mostly on communicating with people who already agree with them and turning them out to vote,” Fleischer says. “But what we’ve learned by having real, in-depth conversations with people is that a broad swath of voters are actually open to changing their mind. And that’s exciting, because it offers the possibility that we could get past the current paralysis on a wide variety of controversial issues.”

It took a devastating loss at the ballot box for Fleischer to see the political wisdom in heart-to-hearts with strangers. In 2008, he was in Ohio mobilizing African-American and Latino voters for Barack Obama when California residents passed Proposition 8, banning same-sex marriage in the state. Fleischer headed west to work with the Los Angeles L.G.B.T. Center, which houses the Leadership Lab, and proposed an unusual idea to his new colleagues: Canvassers should talk to Prop 8 supporters about why they had voted against same-sex marriage. Then they should try to change the voters’ minds.

The idea grew out of Fleischer’s own experience as a “Jewish, liberal gay kid” in Chillicothe, Ohio. He likes to say that he has been talking to people who disagree with him since he was 4. “If I would have only talked to people who agreed with me, I would have only talked to my mom and dad,” he told me. “Interacting with people different than me was a normal thing, and certainly not undesirable or scary. It’s almost the opposite of growing up today in the age of Facebook and political polarization, where it’s easy to always be among like-minded people, your self-isolation complete before you have your first beer.”

At first, Fleischer and his team tried cerebral arguments and appeals to fairness in their doorway conversations with same-sex-marriage opponents who didn’t express deep religious objections. “That failed miserably,” he said. Eventually, the canvassers tried eliciting more emotional experiences. They urged voters to talk about anyone they knew who was gay or lesbian — and, more important, to speak about their own marriages. “That changed everything,” Fleischer told me. “Most people consider marriage the most important and meaningful thing they ever did. Talking about marriage brought up deep emotion. If marriage was the most valuable thing in their own life, wouldn’t they also want their gay friends — or gay people — to experience it, too?”

Though Fleischer thought his new approach was working, he wanted to know whether the persuasion lasted. During a 2013 trip to New York City, he visited the Columbia University political-science professor Donald Green, whose experiments on voter behavior — including his findings that canvassing is a more effective mobilization tool than telephone calls or direct mail — partly inspired a focus on building a ground game, a strategy mastered by the Obama campaign.

Green was skeptical that the canvassers were as persuasive as they thought they were. His previous research suggested that “people don’t change their mind very easily, and when they are persuaded to think differently, the effect is usually temporary,” he told me. But he also knew that political persuasion had not been studied often. “Remarkably, we don’t know very much about what forms of campaign communications are most persuasive,” he said. Green connected Fleischer with Michael LaCour, then a U.C.L.A. graduate student in political science and statistics, who said he could design a study to assess the long-term effectiveness of Leadership Lab canvassers at increasing support for same-sex marriage among voters in Los Angeles who had supported Prop 8. LaCour, joined late in the process by Green as a co-author, published the results in the December 2014 issue of Science. The study claimed to find that though both gay and straight canvassers were effective at the door, only voters contacted by gay canvassers remained persuaded nearly a year later.

The study made international news and seemed to confirm what many gays and lesbians believed in their guts: that knowing a gay person is a powerful antidote to anti-gay bias. It also seemed to bolster the “contact hypothesis” theory of prejudice reduction, which finds that personal contact decreases bias against a minority group. Previous research, though, including a study of teenagers in an Outward Bound program assigned to either mixed-race or all-white groups, suggested that lasting prejudice reduction happened after weeks of regular contact. LaCour appeared to be breaking new ground, showing that one brief but memorable interaction could reduce prejudice.

Broockman and Kalla were intrigued by LaCour’s findings and hoped to replicate it for an experiment measuring the Leadership Lab’s transgender canvassing. But the more they analyzed LaCour’s study design and results, the more problems they found. Yes, Leadership Lab volunteers had spoken to voters in Los Angeles about gay marriage. But when pressed, LaCour couldn’t produce any evidence that he had conducted the follow-up surveys of voters that would have been essential to measuring canvassing’s long-term influence. He also admitted to lying about having received funds for his study from several organizations, including the Ford Foundation.

A shocked and embarrassed Green requested that Science retract the study; soon after, Princeton rescinded a teaching offer to LaCour. News of the retraction stunned Fleischer, who worried that the Leadership Lab’s marriage canvassing would be tainted by association. He vowed to keep at it, but soon there was no need. When the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage nationwide in 2015, Fleischer and his team could turn their focus to the next L.G.B.T. battlefield: transgender rights.

Though there is scant research on transgender prejudice, what is known suggests transgender people face “widespread prejudice and discrimination,” Aaron Norton and Gregory Herek wrote in their 2012 study of heterosexual attitudes toward transgender Americans. The year before, a survey of more than 6,000 transgender and gender-nonconforming people revealed that an astonishing 41 percent had tried to commit suicide.

To test whether transphobia could be overcome during a face-to-face encounter, Broockman and Kalla measured a 2015 canvassing effort in Miami by volunteers from the Leadership Lab and SAVE, a local L.G.B.T. organization. The groups feared a backlash against a recent ordinance that prohibited discrimination based on gender identity. The experiment divided voters into a “treatment” group engaged in a conversation intended to reduce transgender prejudice and a “placebo” group targeted with a conversation about recycling. Before the canvass conversations, both groups completed what they believed to be an unrelated online survey with dozens of social and political questions, including some designed to measure transgender prejudice. After the canvass, the groups filled out four follow-up surveys, up to three months later.

Broockman and Kalla found that the treatment group was “considerably more accepting of transgender people” and that a single, approximately 10-minute conversation with a stranger “can markedly reduce prejudice for at least three months.” Unlike LaCour’s invented finding that the messenger matters more than the message, Broockman and Kalla found that both transgender and nontransgender canvassers were effective. “It’s too bad that the takeaway was that only gay people could persuade people about gay marriage,” Broockman says about LaCour’s retracted study. “Everyone basically ignored the canvassing aspect, and that the message and the quality of the conversation at the door is what seems to matter.”

Broockman and Kalla point to Leadership Lab canvassers’ ability to engage voters in two prejudice-reduction behaviors at the door: “perspective taking” (the ability to empathize with another’s experience) and “active processing” (deep or effortful thinking). Both were on display during many of the canvass conversations I observed, including the one with Nancy, the woman who moved to a five from a 10 after watching the opposition video.

“Is this the first time you’ve thought about transgender people?” Fleischer asked her soon after she backtracked.

“Yeah, I would say so,” she said. “I know it exists, and I hear stories, and I see them on TV. But I don’t have any friends like I do my gay friends.”

Fleischer nodded and removed a picture of his friend Jackson from his wallet. “For me, I never had a transgender friend I was really close to until I was 56,” he said, handing Nancy the picture. “Jackson grew up as a girl, but he knew even when he was 5 or 6 that he was really a boy. It was only in his 20s that he started to tell his folks the truth, and he started making the transition to living as a man. He’s married to a woman now, and he’s so much happier. And he can grow a better beard than I can!”

Nancy laughed. “That’s the thing — they’re happier when they come out, whenever everybody knows,” she said. She seemed to be connecting Jackson’s experience to that of her gay friends.

“Right, because otherwise you have the biggest secret in the world, and everyone thinks something about you that’s not true,” Fleischer said, before pivoting to a story about Jackson’s being demeaned by a waiter in a restaurant. “I don’t like seeing people mistreat Jackson. To me, protecting transgender people with these laws is just affirming that they’re human.” Fleischer then steered the conversation to Nancy’s experiences with discrimination. “You’ve probably had a time when people have judged you unfairly?” he asked.

“Oh, yes,” Nancy said. Over the next few minutes, she recounted several instances of racism after moving to Los Angeles from Central America with her husband. Still, she didn’t appear emotional in retelling the experiences. Fleischer wasn’t surprised; people rarely feel safe enough at first to express deep hurt. It usually isn’t until Fleischer opens up about his own experience — including feeling different in his small, conservative Ohio town — that voters feel safe to “get vulnerable, too,” he says. Nancy had mostly dismissed Fleischer’s “how did that make you feel?” questions, but his personal story prompted a shift. As Fleischer returned to the discrimination she had faced, Nancy paused and said, “It felt terrible.” A few minutes later, when he asked her if she saw a connection between “your experience and how you want to treat transgender people,” she said she did. “I see transgender people as the same as I see myself,” Nancy told him. She ended a solid 10, a rating he was confident could survive opposition messaging.

Earlier that morning, Leadership Lab volunteers sat on stackable chairs and watched video clips of front-door encounters on a projector screen. Fleischer’s team videotapes many of its conversations with voters, then “analyzes the tape like a football team might so we can figure out what’s working and what’s not,” explained a field organizer, Steve Deline.

Knocking on a stranger’s door is scary, and a lot of that morning’s training session was spent boosting the confidence of first-time canvassers. The leaders worked to keep the mood relaxed and optimistic. Fleischer does improv in his spare time, and the training sometimes felt like a well-oiled comedy routine. When the subject turned to potentially awkward initial encounters with voters, the Leadership Lab staff member Laura Gardiner and the longtime volunteer Nancy Williams (who is transgender) did some front-door role-playing.

“Hi, my name is Laura, and I’m with the Leadership Lab,” Gardiner told Williams, channeling a shy first-time canvasser. “Do you have a few minutes today to talk about transgender people?”

Williams played a busy voter. “No, I’m sorry,” she said. “I have to teach my hamster to speak Finnish today.”

Gardiner turned to the volunteers. “We want to avoid asking for permission,” she told them. “Just dive in. Treat it like the most normal thing in the world. Like, of course we’re on your doorstep on a Saturday talking about transgender issues!”

Moments later, Williams reminded the volunteers to be open and nonjudgmental. “We’re asking voters not to discriminate, to be less prejudiced, and we need to walk that walk,” she said. “That means not making assumptions based on the voter’s age, race or their religion. Some folks may have a crucifix on the door. That doesn’t tell you about the person inside.”

On this particular day, volunteers would be canvassing in a predominantly black neighborhood, so Gardiner reminded them to be sensitive to experiences of race-based discrimination. “What an African-American person has faced because of their race is not the same as the discrimination that I’ve faced for being bisexual, or that my friend has faced for being transgender,” she told the group. “But there is a similarity, because at the root there’s the feeling of being judged, of having someone make assumptions about you, and that does not feel good.”

But sometimes the gulf between the volunteer and the voter can seem insurmountable. After the first canvass I attended, the Leadership Lab project manager Ella Barrett seemed uncharacteristically sullen. When I asked how her day went, she shook her head and recounted a series of disheartening conversations with voters she couldn’t persuade. In one, a social worker (“a social worker!” Barrett marveled) announced that being transgender is a mental illness; in another, a man matter-of-factly said he hoped to develop a “straight pill” to change gay people.

Though not all voters would engage emotionally, I was surprised by how many did. Canvassers often had to politely extricate themselves after 20 minutes — voters were sad to see them go. “If only I could have 10 minutes with Ted Cruz,” Fleischer said once. He was only half joking. Fleischer has an unwavering confidence in his ability to persuade most people to be “more empathetic and less prejudiced,” and his optimism is shared by progressive groups who train with him. The day before one canvass, representatives from an animal rights group told me they hoped to better understand how to help people connect emotionally to animal welfare.

Fleischer is especially interested in learning whether deep canvassing can affect people’s thinking on two issues — racial prejudice and abortion rights. Beginning in 2014, the Leadership Lab teamed up with Planned Parenthood to canvass in support of pro-choice policies. Though the abortion debate is less obviously rooted in prejudice than transgender discrimination, Fleischer and his canvassers noticed that many voters reacted negatively to a short video of a middle-aged woman recounting having an abortion when she was 22. People would often be “very judgmental” of the woman on the video or any woman who had had an abortion, Fleischer said. To combat that, canvassers tried to get voters to reflect about challenging decisions they had made in their own sex lives or relationships — or times they were judged harshly. Volunteers also encouraged people to talk about anyone they were close to who had an abortion.

Eager to know if his abortion canvassing was persuasive, Fleischer asked Broockman and Kalla to measure it. But the researchers found that the persuasion attempts had “zero effect,” Broockman said. Still, Fleischer isn’t ready to give up. “Because abortion is such a politically polarized issue,” he said, “it could just be that we have to get better at making voters trust us and open up.” But it could also be that the Leadership Lab’s transgender canvassing success is an anomaly. While a discussion of transgender rights can trigger deeply ingrained feelings about sex and gender roles, the issue is also a fairly recent political consideration for many people. Melissa Michelson, a political-science professor at Menlo College in Atherton, Calif., who studies voter mobilization and public attitudes on L.G.B.T. issues, told me that changing people’s minds about transgender rights might simply come down to “which side gets to a voter’s door first to do the persuading.”

What’s the best way to convince a voter at the door? Though most political canvassing today is focused on mobilizing supporters, an increasing number of researchers, think tanks and campaign operatives have “turned their attention to persuasion in the last few years,” says Columbia’s Donald Green.

Jeremy Bird, a Hillary Clinton adviser who was the national field director for Obama’s 2012 re-election effort, told me that his team conducted a number of experiments to try to have a greater impact when canvassing. “We studied everything, from the kinds of conversations we should be having to the characteristics that made a voter persuadable,” he says. “We trained our volunteers to connect with voters at the door on a personal and values level, not to talk at them with scripted talking points. I think people don’t talk enough about the focus on persuasion we had, because the story line became, ‘Oh, they won because turnout was so high.’ ”

Becky Bond, a Bernie Sanders campaign adviser and an admirer of the Leadership Lab’s work, says that the Sanders campaign has focused on marshaling the enthusiasm of volunteers to persuade people. “I can’t think of a campaign that’s put more volunteers on the ground in a primary season to have quality, face-to-face conversations with voters,” she told me.

Still, the Leadership Lab is unusual in its focus on quality over quantity. A typical state or national campaign, even one with a ground-game focus, doesn’t want its volunteers spending 10 or 15 minutes at a door. “If you’re talking about having real, quality conversations with voters, you can’t bring that to scale without a really large number of people,” says Tim Saler, a Republican strategist at Grassroots Targeting, which works to mobilize and persuade voters. “Technology has helped a bit with the scale challenge, but there’s always the question: Do you knock on as many doors as possible, or do you knock on fewer doors and have potentially more fruitful interactions?”

There’s also a lot that can go wrong when fresh-faced canvassers descend on unfamiliar neighborhoods. In 2004, for example, some 3,500 orange-hat-wearing Howard Dean supporters (many bused in from around the country) managed to annoy Iowa voters days before the state’s Democratic caucus. “The curse of the orange hats,” read a headline in Salon. There are other potential problems. “Canvassers can get mugged, they can get lost, they can get attacked by wild geese,” Michelson told me. “You don’t know if they’re at McDonald’s on their iPhone, and you can’t always be sure what they’re saying to voters. That lack of control scares campaigns. It’s much easier to put all your volunteers in a cozy phone bank where everyone gets to hang out and eat pizza.”

Though Fleischer prefers talking to voters face to face, he isn’t opposed to sequestering volunteers in a phone bank to help L.G.B.T. activists in another state. In 2014, Fleischer and his team modified their canvassing work to persuade and mobilize voters by phone. Leadership Lab volunteers spoke with 3,330 residents in Pocatello, Idaho, a small, heavily Mormon city facing a ballot referendum that would have reversed a local nondiscrimination ordinance protecting gay and transgender people. The effort helped defeat the anti-L.G.B.T. ballot measure by a mere 80 votes.

After a long day of canvassing on that Saturday, tired but exuberant volunteers returned for a debriefing. One canvasser stood up and spoke of moving a man to a seven from a three. Another — a tattooed student who identifies as gender-nonconforming — proudly recalled persuading a voter “who clearly had no experience with anyone who identified as being outside the gender binary. He said I blew his mind, and that he would never forget the conversation we had!” Meg Riley, a 60-year-old Unitarian Universalist minister from Minnesota who volunteers with a racial-justice group, recounted her eventful day. Her second conversation, she said, was with a black man in his 50s who was a seven on the 10-point scale. The man’s daughter, though, would have none of it: She practically pushed him out of the way to tell Riley they were a 10. “I’m with Black Lives Matter, and I know a lot of trans people,” the woman told Riley. “We’re a 10! This family is a 10!”

Several of Riley’s conversations proved poignant. She told voters about her own transgender child, Jie, now an adult. She recounted that when Jie was 3, the toddler responded to a question about possible Christmas presents by asking: “Could Santa turn a girl into a boy?”

Riley’s devotion to Jie had a visible impact on several voters, including the mother of a 7-year-old girl. The woman eventually told Riley that she had voted against gay marriage in California, but that she now regretted that choice. “I made a mistake,” she said. On the issue of transgender rights, the woman seemed mostly supportive but stopped at a nine. She said she was trying to evolve on the issue, though. As Riley prepared to leave for the next house on the block, the woman called out. “Give me a few years, and I know I’ll be a 10!”