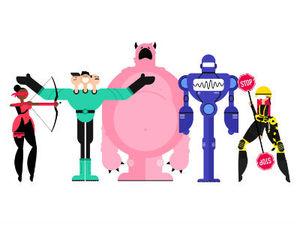

Since 2008 we’ve produced hundreds of videos for charities at Nice and Serious. Some have been a big success, others less so. But over time we’ve seen a familiar pattern emerge; the faces of five fiendish villains we all struggle to fight.

You might recognise some of them. We’ve painted a picture of those villains along with our tips to defeat them.

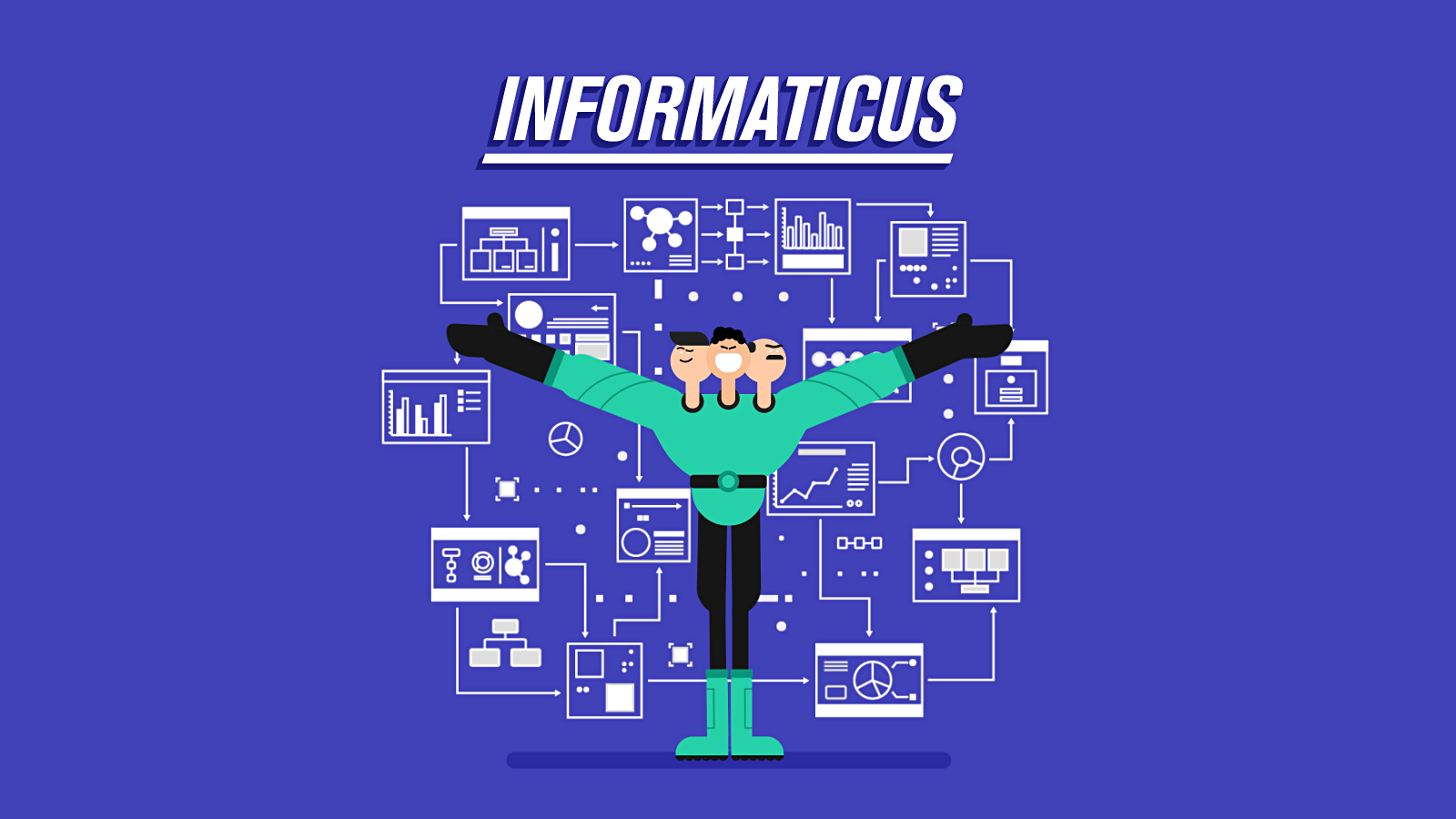

Informaticus

Meet Informaticus. He’s probably the most common villain we encounter. He overwhelms viewers with facts and figures, to the point where they disengage and drop-off. Why? Because humans don’t respond well to numbers; as it takes time for us to process them and they don’t emotionally resonate with us.

How to defeat him

The story is your greatest weapon against Informaticus. We can’t get enough of a good narrative. Find something tangible and human and recount the details. Have confidence that from the specifics of the story, viewers will see the bigger picture. Don’t forget audiences expect to be entertained by video content, not just informed. And always ask yourself: why would anyone want to watch this? If you can’t think of a good reason, keep working on the story.

Cautious Nauseous

This is Cautious Nauseous, a fiendish villain that feeds on your fears and anxieties. She knows you’ve got a lot riding on the film production – people to please and targets to hit – and she’ll convince you to play it safe. The result? A video that’s uninspiring or unsharable.

How to defeat her

First of all, you need to become comfortable with some level of risk. Secondly, push your creative team (internal or external) to develop original creative ideas that meet your objectives. Thirdly, try and road test your concepts and scripts with colleagues, friends and family to get a fresh perspective. Finally, if you’re ambitious with your film, you’ll need to bring key stakeholders along with you from an early stage.

The Jargonaut

If you know a lot about a subject, you’re vulnerable to the Jargonaut. It represents a video with a robotic voice over and a script peppered with jargon. The result? People are sent to sleep.

How to defeat it

You have to fight the Jargonaut on two fronts. The first is language. Keep sentences short, words simple and the tone conversational. Read everything out loud – it will help highlight stumbling blocks. The second front is voice. Avoid a cold, generic voice over (sometimes referred to as Mid-Atlantic). Each accent has its associations, for example, in the U.K. a Scottish accent is considered trustworthy and a Geordie accent is considered friendly. So choose an accent that fits your organisation.

Miss Hit

Miss Hit is a villain without a target. She releases arrows in all directions, hoping one will hit. She represents a brief without a target audience, or an audience which is far too broad. Sometimes she gets lucky and hits the target, but mostly she misses, because it’s hard to judge the impact without a target audience in mind.

How to defeat her

The most effective way to defeat her is to set a narrow target audience. And the good news is this is starting to become commonplace. But it’s no good defining a target audience if you don’t put it into place. Which is why we recommend creating a persona, and judging the creative against it. The result is that feedback goes from ‘I don’t like this because’ to ‘I don’t think Sarah will like this because’. This approach forces you to judge ideas more objectively.

The Blubbersaurus

The Blubbersaurus is a powerful beast. It represents the overuse of sorrow; the video smothers your audience in despair. The result? People have little sense of hope or agency. And if this approach is taken too often, it can leave your audience desensitised and disengaged with your cause.

How to defeat it

The key is not to fight the Blubbersaurus, but to befriend it. To evoke emotion is a powerful communication tool; a sorrowful scene can be a strong motivator to act. After all, jeopardy is a key part of a good narrative. But it’s important that you use emotional stories sparingly, and you give your audience a genuine sense of agency – by taking action they can help solve the problem you’ve just exposed them too.

Regardless of whether you work in a charity, corporate or agency, we’re all susceptible to the five villains. What’s important is that we familiarise ourselves with their fiendish faces and be mindful about the creative decisions we take in the film production process.