5 Online Security Steps to Take Now!

These days, online security is as essential as the basic security measures you would take for yourself and your material possessions in your daily life. With reports of government surveillance on activists, academics, and civilians on the rise, taking security precautions to assure you and your data are safe online is a necessary step. Here are our five must-do tips on how to maintain data security online and resources for why online safety and digital freedom are, in fact, an LGBT matter.

- Install ToR and browse LGBT-related content through the ToR Browser. By bouncing your communications off multiple networks, the ToR browser ensures your location, identity, and the content you’re browsing to only be known by you. The ToR browser can be used on Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux (as well as launched through a USB) without the need to install software.

You can download it for your computer here.

For Android devices, try ToR’s project Orbot. - Use an anonymous email on ALL social media sites.

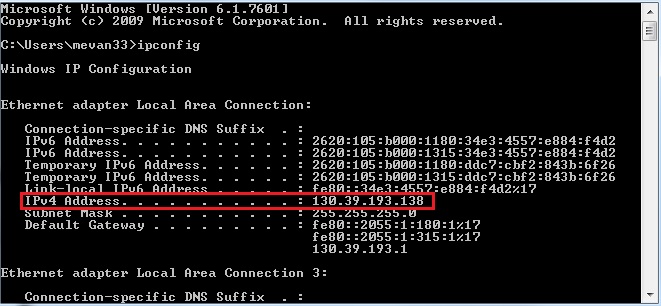

Nowadays, all social media sites demand an email to log in and to create a profile. Many apps also require you to sync with your Facebook or Gmail. All these profiles and apps store information and can make tracking your movements online easily discoverable by governments or other parties interested in your information. It is best to create an email address that is anonymous and separate from your personal email.Unfortunately, the most popular email services are not known to be the safest in terms of online security as companies and governments can request access to your information or cater advertisements based on your cookies and search history (if you are browsing online and don’t want record of it in your search history – make sure to browse incognito!).These steps for anonymity online are particularly important when organizing around sensitive subjects such as gender and sexual and bodily rights. Unlike corporate email services which rely on advertisements and corporations to maintain their services, RiseUp is a non-corporate, volunteer run email service. While RiseUp offers less space than corporate email service providers, they encrypt incoming/outgoing traffic, do not disclose your location/IP address, and don’t log your internet addresses. RiseUp has been used by organizations and groups globally to ensure safe and encrypted communications. Join the movement for Digital Security and switch to RiseUp here. - Mask your IP Address.

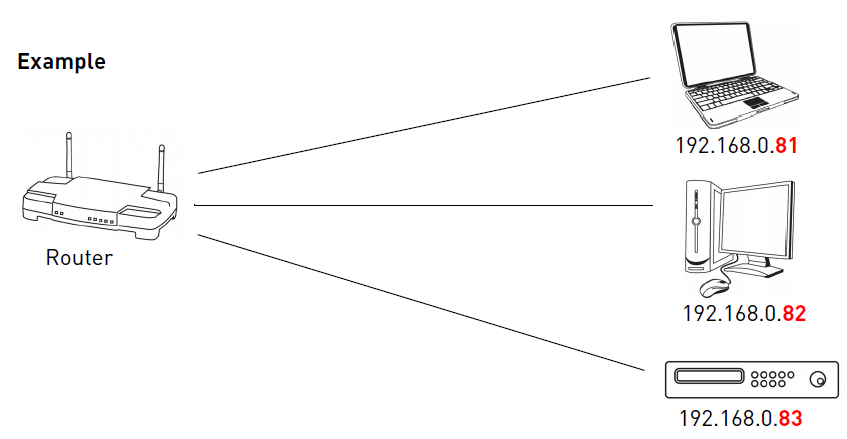

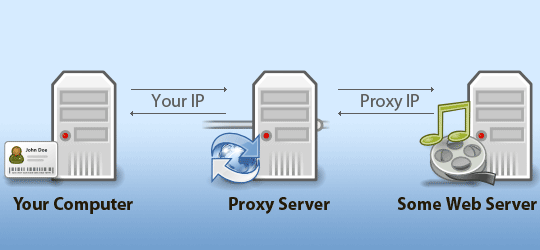

Your IP address is just like your home mailing address in that it is your personal unique identifier. Since every device on a network has it’s own IP address, you may prefer to mask your IP when browsing websites (particularly on sensitive subjects such as LGBT rights). To do so, you would need to use a proxy server to bypass your network and operate outside of it as well as mask your IP address. Proxy.org has an abundant resource of proxy servers available for your use. Make sure to check the pros and cons to any proxy server you intend to you as each offer different services and varying degrees of anonymity online. - Set up two-step verification for ALL of your social media and email services.

Due to hacking, identity theft, data leaking, and other online security risks; most big online companies have adopted heightened security measures with a two-step verification policy. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google, and Evernote each have an option for two-step verification to ensure your accounts are only accessed by you. This requires users to have a security code which is usually automatically generated and sent via text to the users phone as well as enter their password to access their information.

Here’s how to set each one of them up:

- Facebook: To turn on your two-step verification on Facebook you need to enable login approval. Go to Settings > Security > Login Approvals and enter your cell phone number. Once this has been enabled, Facebook automatically sends you a text with an access code every time your account is accessed from an unknown device.

- Twitter: To set up two-step verification on Twitter, go to Settings > Account Security > “Require Verification Code When I Sign In”. This will require you to confirm both an active email address and cellphone number to your account. Each time you access your account from a new device, twitter will send you a fresh code to that number.

- LinkedIn: LinkedIn tends to hold a lot of personal professional information as well as what you share with your connections and the general public. If you have a profile on LinkedIn (as well as all your social media accounts), it is advisable to set up two-step verification. To do so go to Account & Settings (scroll over profile icon for options to appear) > Privacy & Settings > Account tab > “Manage security settings”.

- Google: To set up two-step verification on Google, login to your account on google then scroll to the top right corner of Gmail and click on Settings > Accounts > Change account settings.

- Apple: Two-step verification on Apple takes slightly longer to set up then some other accounts. To do so go to “Manage your Apple ID” > “Password and Security” >”Get Started” > follow the onscreen instructions. Apple will then send you an email in three days, with instructions on how to finalize the two-step verification process.

*Be wary of your “location settings” and “app access” (also located in your general settings and your app settings) on all of these social media sites.

5. Use Alternative Chatting Sites to Communicate and Organize*

In the 21st Century, most of our communication and organization is done online. When the Arab Spring took place in Tunisia and Egypt, most organization and coordination for the protests took place on Facebook groups and chats as well as Twitter. However, these are not the safest modes of communication to use as these sites are increasingly cooperating with governments to share information when requested. In order for you to organize and communicate openly without the fear that your conversation is being logged or stored somewhere.

Here are some alternative chatting sites / apps you can use to make sure your information is as secure as you can possibly make it:

Cryptocat is a fun, accessible app for having encrypted chat with your friends, right in your browser and mobile phone. Everything is encrypted before it leaves your computer. Even the Cryptocat network itself can’t read your messages. Cryptocat is open source, free software, developed by encryption professionals to make privacy accessible to everyone.

“Off-the-Record” Software can be added to free open-source instant messaging platforms like Pidgin or Adium. On these platforms, you’re able to organize and manage different instant messaging accounts on one interface. When you then install OTR, your chats are encrypted and authenticated, so you can rest assured you’re talking to a friend.

ChatSecure: Encrypted Messages on iOS and Android. ChatSecure is a free and open source messaging app that features OTR encryption over XMPP. You can connect to your existing accounts on Facebook or Google, create new accounts on public XMPP servers(including via Tor), or even connect to your own server for extra security.

All of the above chat software and apps require an Internet connection provided by either Wifi or your mobile carrier. As we witnessed with the Arab Spring and other moments of national political tension, governments can switch off or limit connectivity in public spaces to make communications about public actions, safety protocols, and other information between activists and citizens even harder to share to the widespread audiences that social media platforms provide. This is where FireChat comes in.

FireChat is the messaging app that works when and where others cannot. FireChat uses peer-to-peer mesh networking technology to connect people and mobile devices even when no Internet connection or mobile data service is available. FireChat has been among the top 10 social networking applications in 124 countries. From Burning Man to Taiwan, HongKong, Delhi, Moscow, Manila, Paris, Srinagar, Kuala Lumpur and Austin, pro-democracy protesters, disaster relief organizations, leaders, and artists are choosing FireChat to stay connected to their friends and communities.

*Always check what each service provides, what information – if any – is stored, and if your traffic is encrypted.

Further Reading

Egypt jails eight men after ‘gay marriage’ ceremony on Nile

Russia bans five online LGBT youth groups under anti-gay law

‘Perfect Surveillance,’ Says Edward Snowden, Could Have Snuffed Out the LGBT Movement. He’s Right.