Campaigns shouldn’t be easy!

Campaigns shouldn’t be easy! Why difficulty and motivation matter so much in campaign design

Thoughts on Dan Ariely’s book “Payoff”

“Knowing what drives us and others is an essential step toward enhancing the inherent joy, and minimizing the confusion, in our lives” – Dan Ariely

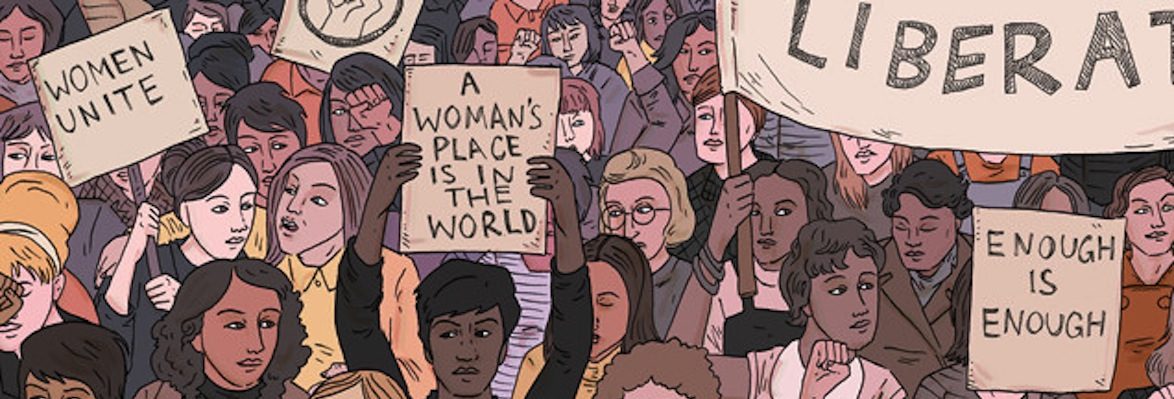

The work of Psychology and Behavioral Economics Professor Dan Ariely focusses on the distinction between the concepts of ‘meaning’ and ‘happiness’. His work illustrates that the things in life that might give us a sense of ‘meaning’ don’t necessarily give us a sense of ‘happiness’. And yet, for so many of us, the pursuit of ‘meaning’ and ‘happiness’ is our motivation. Similarly, any successful campaign should be seeking to find the ‘bliss point’ that allies these two motivations.

The key drivers to human motivation are

- Our sense of identity;

- The need for recognition;

- A sense of accomplishment;

- A feeling of creation; and

- Most importantly, a connection to others.

For Ariely, a sense of ownership greatly influences our motivation. As most of us would intuitively recognize, the more that a person feels a sense of ownership over something, a cause, the more likely they are to be motivated to achieve it. When considered in the context of campaigning, the consequences of a sense of ownership over an issue is compelling. It suggests that in order for people to be feel motivated to influence change, those who are targeted by the given campaign should be the owners of that change. This means that traditional approaches to campaign design, those that have long told us that it is important to tell people they need to change and then show them the ‘right’ model of change, might not be the most effective strategies to evoke change. So, how do we get people to feel a sense of ownership over change?

According to Ariely, campaigns should not be easy. Instead, the effort that is required for a campaign actually inspires a sense of ownership in the participants. Meaning that this effort required to cause change also, at the same time, is the very reward that people are seeking. For example, the hugely successful Ice Bucket Challenge is a good illustration of this. The Challenge asked people to set up a fundraising circle, film themselves pouring ice cold waters over themselves, and then distribute the video to their networks. Beyond the innovative and hilarious nature of the action, its sheer difficulty , when compare to changing an avatar or posting yet another selfie, for example, might have been a major driver of the campaign’s success.

So, going against traditional campaign wisdom, he argues that successful campaigns should not be easy. Instead, campaigners need to reflect on having the right balance of difficulty in a campaign, where the action stays difficult enough to be meaningful, but easy enough that people do not feel put off from participating.

In addition to this, the change at the center of the campaign needs to be meaningful so that people are prepared to engage in the ‘difficult’ asks that the campaign makes. To be meaningful, the change should be clear and long term. Nobody wants to invest in a change that will not be sustained. For example, no one wants to quit smoking for just one month. And so campaigns should not shy away from engaging people with a long term process of change, one what has multiple and complex effects. Ultimately, easy and short term asks will not result in change that is meaningful enough for people to engage or invest in supporting that change.

Another key piece of advice that Ariely’s book offers is that campaigns must acknowledge and be thankful for the effort required to participate in them. If campaigns request something that is difficult, they then need to be prepared to guide and support people through the journey, and regularly show gratitude for the road participants have travelled. Last, but not least, is the issue of ‘creation bias’ which refers to the fact that people only feel ownership over things they feel they created themselves. Successful campaigns need to target people in a way that allows for them to creatively participate. Simply liking and sharing campaign content will not be enough.

To summarize, a successful campaign requires three key actions:

1. Making participation difficult and meaningful enough for people to value the change;

2. Allowing people to participate creatively in the change journey; and

3. Acknowledging participants’ effort!