For many years, the Turkish authorities and conservative movements have been known for their crackdown on sexual and gender minorities, as is now often the case around the world.

Faced with vicious attacks and disinformation campaigns trying to frame LGBTQI+ people as different and representing a threat to society, especially to the family, civil society organizations are fighting back using normalization strategies. We met with Ogulcan from the Social Policy, Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Studies Association (SPoD) and Nalan from Muamma LGBTI+ Association to share insights from their latest campaign.

How was this campaign conceived?

At SPoD, we have been campaigning for a long time against targeted attacks. Our approach is always to provide an alternative narrative, without being confrontational. For example, a past campaign was entitled “Türkiye is ready for it” in order to counter the narrative that there was social hostility, especially from people from a traditional background. The opposition is trying to polarize the debate; our strategy is to bring people together.

In 2024, SOGI Campaigns conducted a capacity development project in the country, where 26 participants, including individuals and activists from 23 different organizations around the country, came together on a six-month fellowship programme, during which the idea for a new campaign emerged.

What was the campaign focus?

When we scrutinized the anti-gender narratives spread by anti-LGBTI+ movements in Turkey, the strongest frame seemed to be to claim family values for themselves. One of the highlights of the tactic was the 2024 Big Family Rally, the most powerful street rally of the anti-LGBTI+ movements in Türkiye to date.

These movements keep pitting us against the family, which is clever because families are increasingly seen as a place of safety in the face of political and economic instability.

Our conclusion was that we could not leave the notion of family to be misused in this way, but it left us with a dilemma: how to reframe our position as pro-family, while at the same time not ignoring the fact that families have sometimes been unsafe and unwelcoming for LGBTI people.

We also had to stay neutral on the concept of “family values” because it could easily feed a polarized debate, which we wanted to avoid because fighting over family values is not a fight that we could win. So we shifted the conversation to diversity, inclusion, and equality.

How did you find this balance?

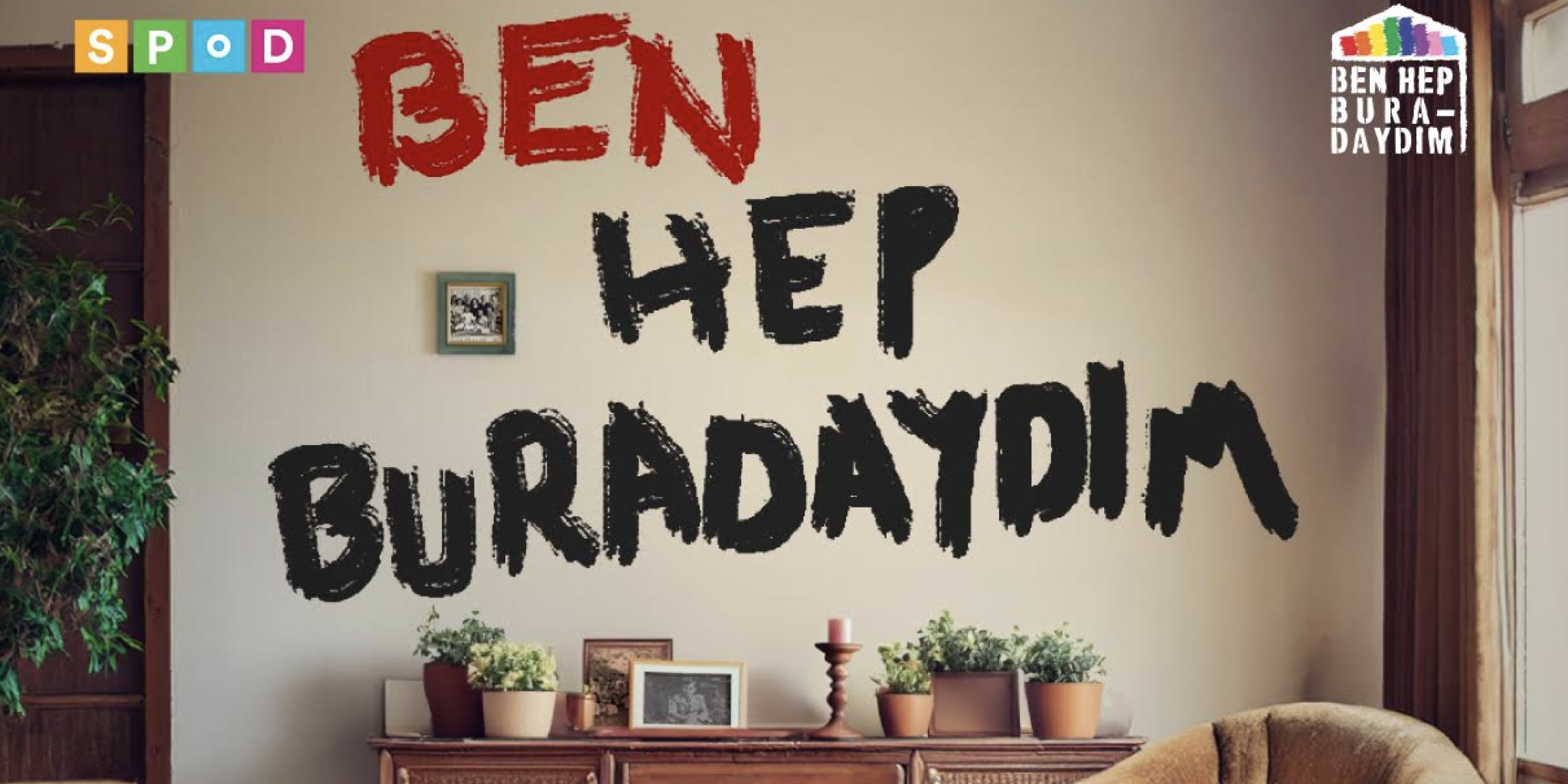

We simply focused on the fact that we are here, we exist, and we are not going anywhere else. It is not a matter of choosing whether we are pro- or anti-family. We are here and that’s it! Against a narrative backdrop that tries to cut us off from the rest of society by making us sound aggressive and look different, we chose to present our realities in the most relatable way for our audiences.

We chose not to represent people but instead symbols of everyday life, so that people could project themselves more easily and not be distracted by representations of individuals, who are necessarily always “different” in some way.

Having said that, we did not shun the debate on the problems with traditional families. We tried to expose the current family situation where domestic labor is exploited, and children are exposed to the government’s political propaganda in poor-quality educational institutions.

Who were your target groups?

We had two major target groups: the LGBTI+ community on the one hand, and parts of the “movable” audience on the other.

For LGBTI+ people, we aimed to reinforce their agency and sense of belonging, in the face of an opposition that always tries to label us as “alien,” “foreign,” and undesirable.

For external audiences, a strong focus was put on younger males with good levels of education, because this particular demographic is emerging as a very vocal force, especially on social media, driving a harmful masculinist narrative. Of course, we did not aim to win over this audience, but rather to disrupt their representation of us, so that at least they would be less vocal. Sometimes a campaign can aim at “just” stopping people from circulating hate speech. We also targeted potential allies in order to broaden the support from society in general.

How was the campaign executed?

We got support from two creative agencies for the development of the video and the social media items, respectively.

Distribution was via our own channels, via organic and paid reach. We reached an audience of 1.5 million, which we see as a great indicator of impact. We were supported in this outreach by coverage from the progressive press, while surprisingly, the conservative press did not provide any negative coverage.

How do you explain this silence?

The campaign was launched in a public rally, which took place in the same location as the anti-LGBTI+ “Big Family Rally.” As part of our action, we distributed donuts (lokma) in memory of Ahmet Yıldız, who was murdered by his father in 2008 because he was gay. This was a crime that deeply shocked the Turkish public. Our action highlighted the damage and dangers of the type of families encouraged by conservative groups, while also promoting our own vision of families, which should be loving, caring, protective, and non-violent.

It was very difficult for conservative movements to raise their voices against this action, as it would have made them look as though they supported the crime, which would have been a poor strategic move.

And what comes next?

A severe lack of funding prevents us from continuing to roll out this campaign, but we realize that the frame of inclusive families must be mainstreamed over a long period of time to produce the intended change in social narrative.

We are in discussions with other movements, such as the feminists who are facing similar dilemmas when denouncing femicides, so we can bring our campaigns together at the narrative level, and all work toward common social change goals.

So, although this particular campaign might stop here, another branch of the same tree is already growing. Let’s hope the fruit from this tree will be sweet and abundant!