This article was written based on interviews conducted with Phong Vuong, LGBTI Rights Programme Manager at iSEE, and information from an article by Advertising Vietnam.

Vietnam’s “Leave with Pride” campaign is the result of a collaboration between the Institute for Studies of Society, Economics and Environment (iSEE), a group that has been at the forefront of the LGBTQI+ movement in Vietnam since 2007, and ad agency MullenLowe Singapore. The viral campaign led to decisive action against conversion therapy practices, still common in Vietnam.

A dire situation

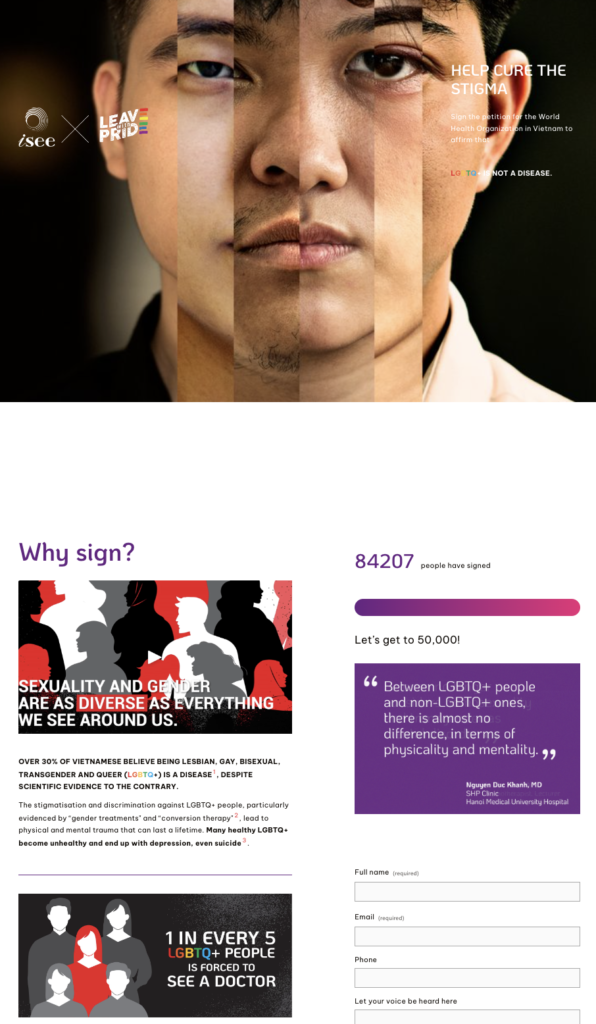

In 2015, iSEE’s study “Is it because I am LGBT” showed that one out of five LGBTQ+ people is forced to see a doctor to get their “sickness” treated. And almost one third of Transgender people in the survey declared being forced to get medical care (29.3%).

As a matter of fact, despite the Word Health Organisation (WHO) having published clear standards at international level that both homosexuality (in 1990) and transgenderism (in 2019) are not to be classified as diseases, Vietnamese health authorities had so far not made any official statement regarding these harmful practices, with their continuous practice resulting in severe physical and mental consequences for LGBTQ+ people.

iSEE had been fighting for many years to get the authorities to act on this.

Authority goes beyond the law.

“While it is very hard to pass a law banning conversion therapy, Vietnam is a very collective society, and we listen to the authorities. In this context, our objective was to get the WHO office in Vietnam to issue a strong statement condemning these so-called therapies,” Phong Vuong said. iSEE would then use this statement to lobby the national health authorities to follow suit.

Because of the political system and framework in contexts like Vietnam, there are limited ways to directly influence policymaking; therefore, public opinions and public pressure are among the most important and useful tools in influencing policymaking. So, iSEE’s strategy was to gather as much public support as possible.

“Too gay to work”

At this time, a Singaporean ad agency, MullenLowe Singapore, had approached iSEE to do a pro-bono campaign on LGBT+ rights. During their initial brainstorming, they were inspired by a famous Swedish campaign from the 80s. At that time, homosexuality was still officially classified as a disease. To protest this, supporters were invited to call in sick to work, stating they felt “a bit too gay/ lesbian today to go to work.” Of course, the campaign was not actually seriously inviting people to do this, but the idea itself was funny enough to get a lot of attention, and the national health standards changed.

The Leave with Pride campaign took the same idea but decided to go all the way to actually implement the call to action.

“Our message was that if being LGBT+ was really considered a disease, then queer people should really be entitled to sick leave. We recruited a doctor who provided a medical certificate to grant sick leave to a handful of volunteers. These volunteers would then face their employer with a sick leave request. This confrontation was filmed in hidden camera style.”

“The volunteers had already decided to quit working at their workplaces. This was one of the last things they did before resigning. We found these volunteers through informal networking – personal contacts and social media,” Phong Vuong shares.

Turning outrage into action

The results of this social experiment were incredible and gave much ground for outrage. The issue was how to use this for political action.

Therefore, the campaign’s next step was to channel the attention and outrage produced by these videos towards a petition to the health authorities.

“We specifically chose WHO because we wanted to take a hard stance and use human rights messaging. It was important for us to target the WHO at the national level rather than at the global level, so that it would really be concrete for the Vietnamese public.”

One step at a time on the way to success

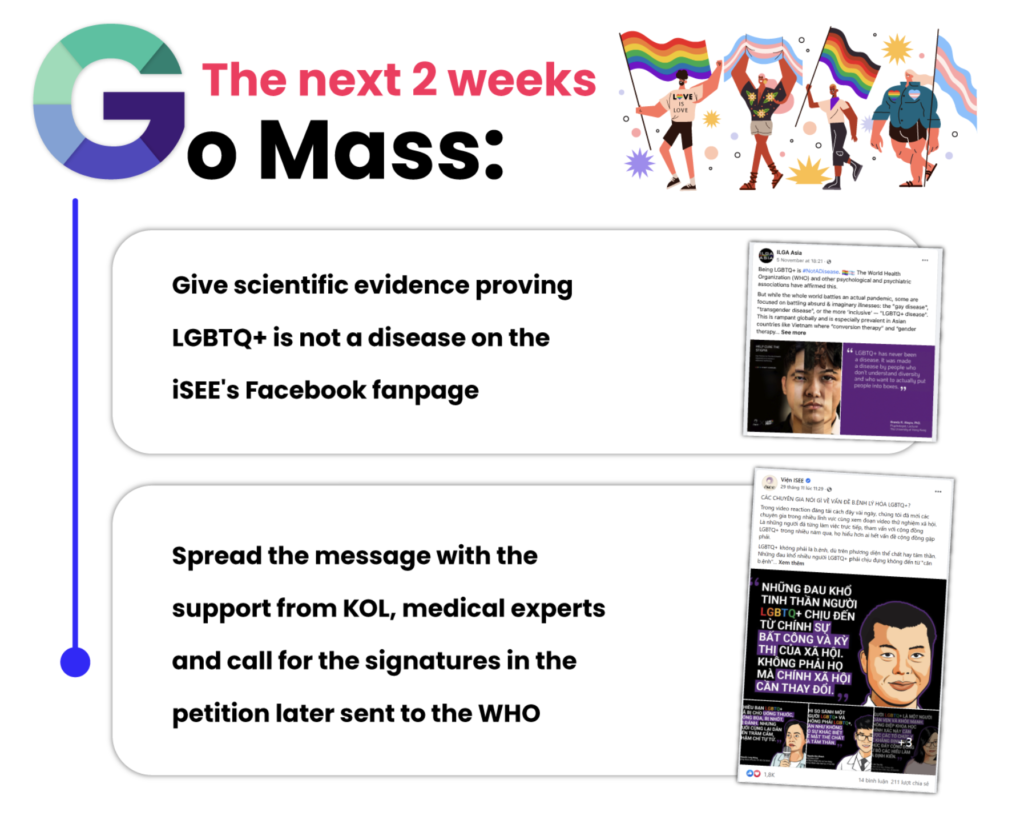

The campaign unfolded in three distinct phases. The social experiment video was released first, providing the “emotional” trigger.

Once the video had gone viral, the campaign released its second video, in which medical experts commented on the issue of the social experiment.

This video provided the authoritative foundation of the campaign, the “rational” argument.

Divide (the labour) and rule

Phong Vuong notes, “iSEE provided the content and the direction of the campaign. The data and the research behind the campaign were done by ISEE. We also played a big role in quality control, to ensure that our content meets human rights standards and doesn’t compromise on the safety, the privacy, and the anonymity of those who appeared in the video.”

The ad agency designed, produced, and disseminated the content. It also provided the infrastructure needed to ensure that visitors to the website signed the petition.

“From ISEE’s perspective, as a research organisation, one of our biggest challenges was stuffing the video with too much information. But it turned out that people didn’t need all that information – what they needed was for us to make the information easily digestible. That is where the professional perspective of the ad agency really helped. They would tell us, “This is fine, you can stop here, and provide the rest of the information in different formats”. There is no point in a video with a ton of great information that nobody watches. Public campaigns are not meant for us – they are meant for the public,” Phong Vuong highlights.

Safety first

Protecting the privacy and anonymity of the participants of the social experiment video was a huge concern for the organisers. “We could not do the campaign without addressing that concern. What we did was that we blurred out the faces of everyone (including the employers), we changed all identifying details, and processed their voices. We virtually made the participants unrecognisable,” Phong Vuong insists.

Success

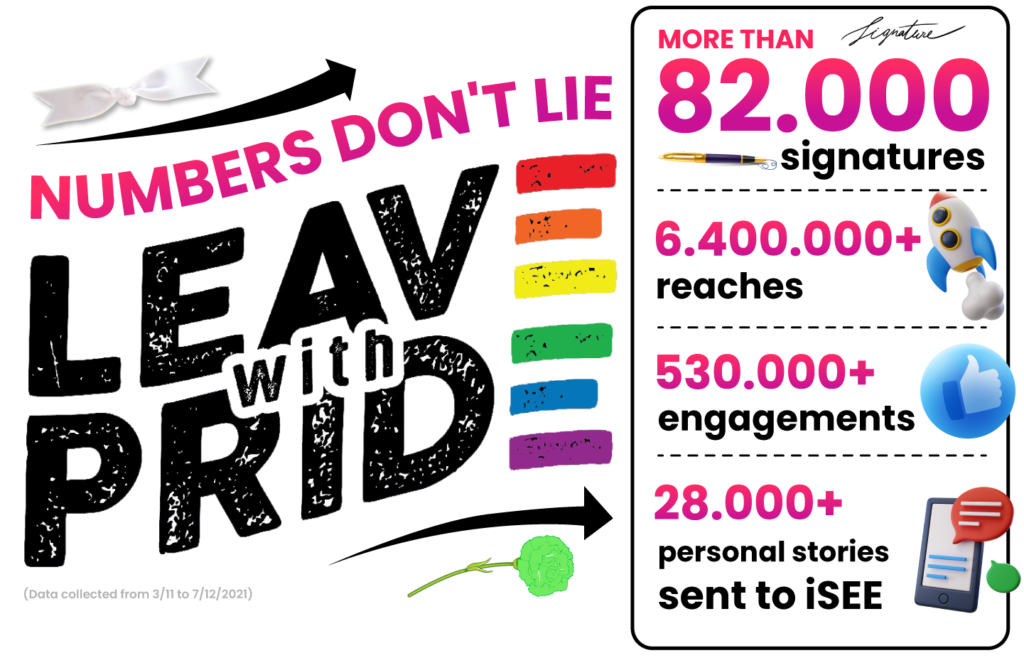

After a long journey with many challenges and obstacles regarding many aspects, MullenLowe Singapore and the iSEE’s efforts in the “Leave with Pride” campaign were crowned with success. Phase 1 of the campaign ended on the last day of Pride Month with impressive outcomes, with more than 82,000 people (160% of the initial target) calling on WHO Vietnam to speak up.

Phong Vuong’s voice resonates: “We got the WHO statement. The Ministry of Health (MOH) went as far as to issue a directive condemning conversion therapy practices and asked the Departments of Health all over Vietnam to review the services that are provided in their provinces and make sure conversion therapy was not a part of those services.

A dispatch of this nature from the most trusted authority on health in Vietnam can scare a lot of people away from trying to practice conversion therapy. The second impact is that young queer people can use this statement to defend themselves, be it with parents or hospitals. As a tool for public education and for LGBT+ people to defend themselves, this is very helpful.”

A long way to equality

It is important to repeatedly underline how the “Leave with Pride” campaign stands on the shoulders of years of prior activism.

As Phong Vuong highlights, “ISEE started in 2007, and one of the first things we did was a research study on public opinion on LGBT+ people, examining newspaper articles and media discourse. What we found was extremely negative. At the time, Vietnam also had a ban on same-sex marriages; same sex couples were not even allowed to have purely ceremonial weddings and would be fined if they tried. So, one of the first public campaigns we did was called ‘I DO.’ The message was that gay people also want to have a family and a partner to take care of them. Asian cultures, such as ours, place a high importance on traditional family support, so we were playing on that. The campaign received a lot of public support. While it didn’t legalise same-sex marriages in Vietnam, it shifted the conversation from the public discourse from looking at being LGBT+ as a social evil to a more realistic portrayal of what it means to be queer.”

Phong Vuong’s historical perspective is a powerful reminder that social change processes are complex, long, and by no means linear.

|

Food for thought The main message of the campaign, that “LGBTQ+ is not a disease,” contravenes the “central” principle in campaigning not to repeat a negative frame, so as to not reinforce its presence in the mind of the public. Like any principle, there can be cases where other considerations are stronger and justify this choice. We have not yet been able to investigate this further. This sequencing of the campaign mirrors how attitudes are being shaped: first, people get triggered by emotions, then they search for the facts and arguments that will legitimise these emotions. This campaign very cleverly followed that exact process. |