This article first appeared on BBC

Zrinka Znidarcic has a new picture-book for her two-year-old son, Patrik. And she can hardly contain her excitement.

“His reaction was complete delight,” she says. “He just took it and immediately said: this is familiar.”

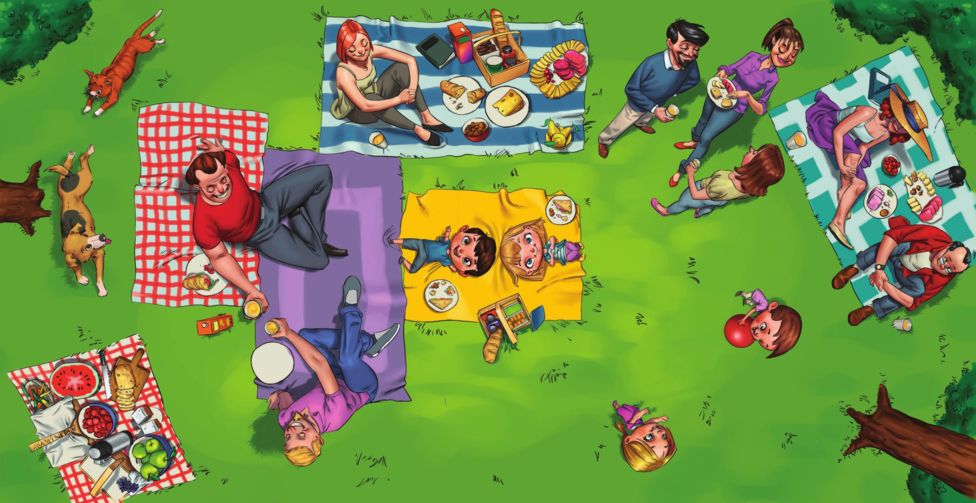

The book in question is called My Rainbow Family. At first glance it looks like many other publications aimed at pre-school children – heavy on full-page, colourful illustrations and light on text.

But it quickly becomes apparent that something different is going on here. For starters, it can be read from the back or the front – as there are two different stories which meet in the middle.

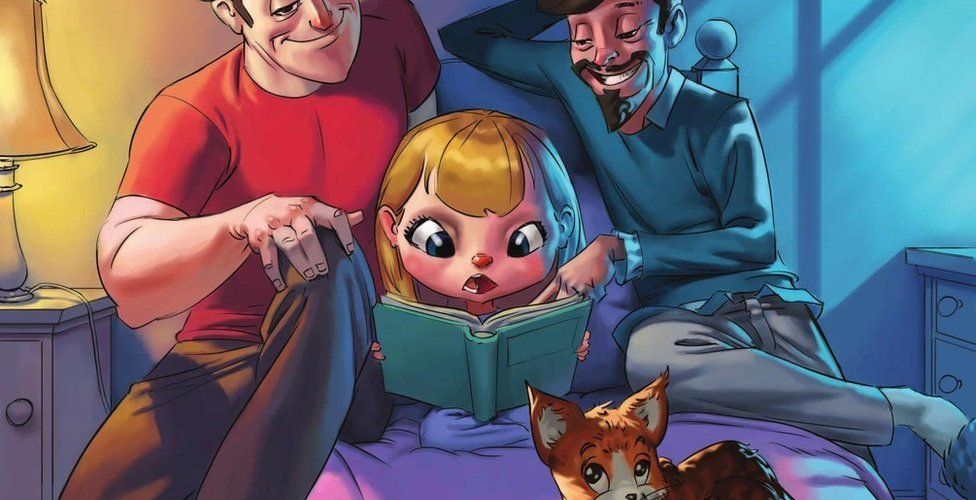

And then there are the characters. A little girl with two fathers. And a young boy with two mothers.

It is the first time that a children’s book in Croatia has depicted families with same-sex parents. And for people like Zrinka, who has been in a civil partnership since 2014, it is a welcome reflection of life in her family.

“We’re very happy,” she says. “Patrik picks his own books for a bedtime story. Since he got this one, it’s always in his favourite two or three. We didn’t explain anything about it to him, he just took it. He says, ‘I want to read the book about me, about my family’.”

My Rainbow Family may be a source of joy to Zrinka and her family. But it is a direct challenge to conservative organisations backed by the Catholic Church. Five years ago, they forced a referendum which blocked the then-government’s plans to legalise same-sex marriage. Now they are taking aim at a children’s picture-book.

One organisation, Vigilare, says its mission is to “promote the original (natural) identity of marriage… between a man and a wife in which children are raised”.

It called My Rainbow Family “homosexual propaganda” and urged the education minister to ban it from schools. Vigilare did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

Senada Selo-Sabic of Zagreb’s Institute for Development and International Relations says there has been a resurgence in conservative forces since Croatia joined the European Union, five years ago.

“Croatia made a mistake during the EU accession process – we silenced and marginalised everyone who didn’t agree with this course of action. The political parties created this image of Croatia being very liberal, progressive and egalitarian. But in reality, it was only one side of the story.”

Rising nationalism

The opposition to a book featuring same-sex parents is just one of the symptoms. There has also been an increase in extreme nationalism and even incidents of Holocaust denial.

A plaque with a fascist slogan was installed near the site of the Jasenovac World War Two concentration camp; it took the authorities almost a year to remove it.

Senada Selo-Sabic says it is a worrying time.

“I hope that what we now see as an upheaval of conservatism is simply a reaction to the silencing period they were subject to – and that this will die down in the future. Otherwise, we are really doomed.”

But the publisher of My Rainbow Family prefers to be optimistic. Daniel Martinovic, one of the co-founders of Croatia’s Rainbow Families support group for same-sex parents, says positive responses to the book have not been limited to minority groups.

“When we first made the book, we only printed 500 copies, because we thought it would mostly be for us, our friends and supporters. But since the story went public we have had lots of parents saying: ‘we are not LGBT, but we would really like a copy of the picture-book so we can show our children and discuss themes of equality, tolerance and diversity’.”

“Maybe this gives us hope for a change – that we’ll move towards a more tolerant society.”

The reaction of the education minister lends weight to Mr Martinovic’s suggestion that while Catholic “family” groups might be noisy, they represent fewer Croatians than the “silent majority” for whom they claim to speak.

Blazenka Divjak ignored an open letter from Vigilare and said that parents had the right to decide whether or not their children should be able to read My Rainbow Family.

Compare that to Britain in the 1980s. Kenneth Baker, the education secretary under Margaret Thatcher, objected to the publication of the first English-language children’s book to feature same-sex parents. He called Jenny Lives With Eric and Martin “blatant homosexual propaganda” – perhaps an inspiration to Vigilare, more than 30 years later.

Attitudes have changed in Britain. And Zrinka Znidarcic is convinced increasing openness will pay dividends in Croatia, with My Rainbow Family playing a role in reducing the negative comments about same-sex parents.

Image copyrightMY RAINBOW FAMILY

Image copyrightMY RAINBOW FAMILY“I have never had a bad experience when people find out I have a wife and family,” she says.

“The best way to change minds is to be civilised, give them a chance to meet us and interact like normal human beings.”