F l/r aming with Pride

TOO PROUD ?

Some years ago, I got a call from a National Council of Muslim organisations, who wanted to react on a poster that was created for the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia. This poster was depicting two girls with rainbow-colored head scarfs holding hands. I was already bracing myself for a tough homophobic conversation but to my utter surprise, the Council’s request was not to protest about the idea of Muslim Lesbians. Actually, they were very supportive of the depiction of sexual diversity among Muslim women (you probably can sense it was a very progressive country, which I won’t name). Their opposition “merely” centered on the attitude of the women: “You see, they explained, the veil is a symbol of modesty. It is not their sexuality that triggers our members, it is the indecency of their attitude[1]”. In other words, they were just “too proud”.

We are in the heart of Pride season and global communications are flooded with the frame of Pride, which triggers just as much exhilaration as acrimony.

While sexual and gender minorities are carrying the Pride frame literally as a flag, opponents voice their (at best) uneasiness by a notion they perceive as (at best) irrelevant, antiquated, and exclusionary.

There are countless moves to try to discredit the “Pride” approach, to make it look like aggressive and indecent instead of what it is: a source of hope and self-respect.

At the other end of the opposition spectrum, we have all raised our eyebrows in disbelief at the idea of a Straight Pride, but daft as it is, the idea reflects that the frame of “Pride” is something that is worth investigating more.

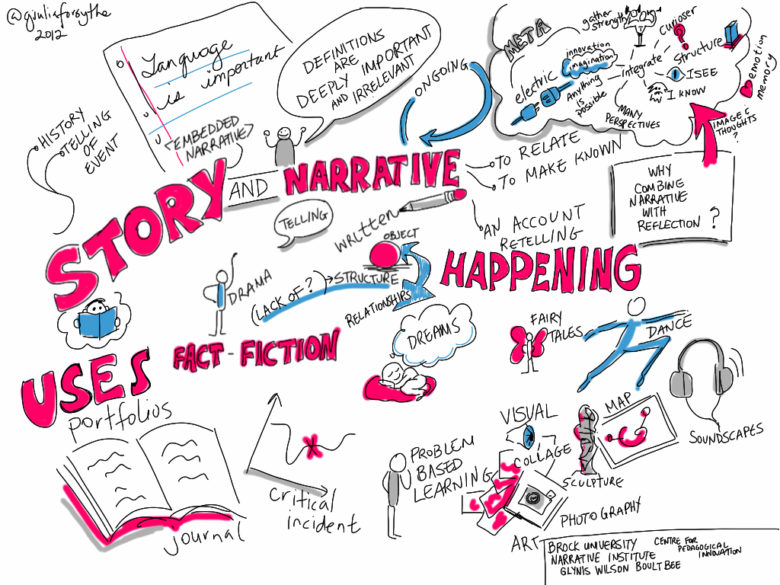

First, a very quick reminder of what framing is: our usage of certain words (and/or images, symbols, etc.) triggers certain pre-existing meanings, representations, notions, values, feelings, etc. that we hold in our minds. They act like shortcuts: The image of a heart triggers the notions of care, pleasure, comfort, and surely other things depending on any particular culture.

Framing is the art of activating these shortcuts, while avoiding triggering the ones we don’t want.

Good Pride Turned Bad

(Hi, Rihanna!)

For sexual and gender minorities, the mere vision of a Pride flag triggers notions of self-worth, protection in numbers, liberation, recognition, fun, and much more. For many of our allies it triggers feelings of celebration, fun, friendship.

But what does “Pride” trigger in the rest of society? At least, what does it trigger in “Western” cultures? This is a big debate, worth of many better articles than this one but let me share a few initial thoughts.

As one of the seven deadly sins, pride has a mixed reputation. On the one hand it is viewed positively as a sign of healthy mental and psychological balance, but take it out of its socially controlled borders and it’ll become hubris, narcissism, arrogance, and vanity.

And this is where the “LGBTQI-Pride” gets tricky: By taking the authority to be naming what can be a source of Pride, and how Pride is allowed to manifest itself, sexual and gender minorities challenge what a given society’s majority feels to be theirs. The distribution of pride and shame is one of the fundamental instruments to shape societies.

Because of its very nature to challenge the ownership of this instrument, Pride has a disruptive effect that goes well beyond our enemies.

Biases reinforce the frames

The notion of Pride is particularly uncomfortable for people when associated with two mental structures: the slippery slope bias and the zero-sum thinking. The slippery slope bias posits that there is an incremental tendency to everything. Therefore, once Pride has become the new normal it will “escalate” into arrogance and possibly (and that’s really the end of the world as we know it) LGBTQI supremacy.

Somewhat relatedly, the zero-sum game mentality implies that for someone to win something, someone else has to lose it. So if LGBTQI people can be proud, it means someone else has to be ashamed. As crazy as this seems to the rational mind, this might well be going on in the symbol-oriented emotional mind.

Because these biases are not limited to our enemies, we have to be aware of the “side-effects” of our use of the Pride frame, of course not to diminish its prevalence because its presence is vital for most, if not all, of us but to balance these side-effects out.

The “zero-sum game” bias for example can be weakened with a few “Proud Ally” signs, or with representations of the future that includes everyone, not just us. The slippery slope biases can be challenged with images of “normalcy”, like rainbow families.

In public representations of Pride, many different messages are visible, and this often provides a sort of “natural” framing balance. But in our own communications, we are much more selective on what we show, share and shine. It is therefore really important that we keep increasing our awareness of the act of framing, and our savviness in how to strategically frame our communications.

Because changing hearts and minds mostly happens under the surface.

Having said that, HAPPY PRIDE !!!!

As said, this issue deserves a stronger conversation. To share your insights, join the Creative Campaigners Facebook group.

[1] I am not going to dwell over whether this is an acceptable stance. Other conversations are needed for this.