An interview with Atlas of Hate co-founder Kuba Gawron

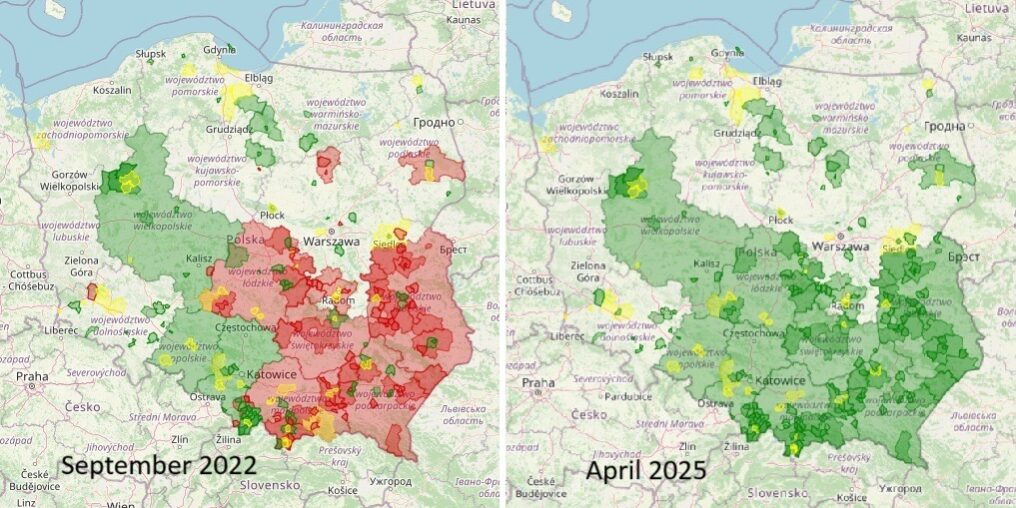

Poland is now officially free of “LGBT-free” zones. Five years ago, at the height of the previous government’s anti-LGBTIQ crusade, over 100 local governments, representing a third of the country, declared themselves to be free of so-called LGBT ideology. In April 2025, municipal officials of the town of Łańcut voted to repeal the last anti-LGBTIQ ideology resolution in the country, inspiring hope that this gender paranoia has been confined to the dustbin of history.

While the campaign to end “LGBT-free” zones in Poland involved grassroots activists and EU officials alike, it was one small group that put these zones on the map. The Atlas of Hate is an interactive and regularly updated online map tracking “LGBT-free zones” in the country. Today, the map is fully green—showing that all battles to scrap these zones have been won.

Scoring cheap political points

In 2019, weeks ahead of the European Parliament and national parliamentary elections, political actors and their allies intensified attacks against so-called LGBTIQ ideology. As Atlas of Hate co-founder Kuba Gawron puts it, the ruling Law and Justice Party just wanted to score cheap political points—by presenting LGBTIQ people as a threat to the traditional Polish family, children, and culture.

“A major hate campaign was launched in the government media and social media. One of its manifestations was precisely anti-LGBT zones – that is, resolutions calling for the removal of LGBTQIA topics from the activities of local government units. Councilors adopted them en masse under the influence of government anti-LGBT propaganda.”

Kuba at the Rzeszów Pride on June 22, 2019. © Kuba Gawron

At that time, Kuba was a co-organizer of the equality marches in Rzeszów, the largest city in southeastern Poland. In the summer of 2019, Karolina Gierdal, his friend and a lawyer working on LGBTIQ issues, asked him if he had a list of these resolutions. That’s when it all started.

“At the time, we had only a vague idea of the phenomenon, based on fragmentary reports from local media. I didn’t have a list, but I started googling for them. It quickly became clear that there were many more of these resolutions than we thought. I set up a table to which I steadily added more items until I had accumulated dozens of them.”

This initiative came to be known as the Atlas of Hate, which Kuba co-founded with other Polish LGBTIQ activists, Kamil Maczuga, Paulina Pajak, and Pawel Preneta.

Watershed moment

Back then, it was still a table, not the map we know today. Yet, their data had already captured the attention of some members of the European Parliament (MEPs), who invited them to present it for a debate in the European Parliament in November 2019 on the situation of LGBTIQ people in Poland.

From left to right: Mirka Makuchowska (Campaign Against Homophobia), Kuba, Kamil Maczuga (Atlas of Hate), Tanja Fajon (MEP from Slovenia, PES faction), November 2019. © The Left

Shortly after the debate, Pawel set up an online map page, drawing from data in the table. This changed everything. “Then there was a real media explosion. The media widely reported on the topic. The graphical presentation of this data proved to be a watershed moment.”

Since its creation, the map has been indispensable to campaigners and decision-makers and critical in keeping this issue in the public eye. “When we started our project, we didn’t think about winning. We were four activists trying to take on over a hundred local governments,” said Paweł.

Putting hate on the map

Atlas of Hate scoured data from two local government sources: public information bulletins, publishing information required by law, and official websites for other kinds of data. Freedom of information laws allowed them to request data from local governments.

Before the age of generative AI, it was pure diligence that got them what they needed:

“I accumulated hundreds of links to official agenda pages in my bookmarks and reviewed them almost daily, checking for updates. I also checked the information using dozens of Google alerts. I also used Google search operators – I saved them in my bookmarks and returned to them regularly. As the site gained publicity, I also got information and documents from outsiders.”

They also cultivated relationships with opposition politicians and local campaigners, who provided them with off-the-record information they could not find online, such as the positions of individual councilors or plans for hostile resolutions.

While the Atlas of Hate has been critical in capturing international media attention on attacks against LGBTIQ people in Poland, the activists did not even have any advertising strategies. As Kuba claims, “simply adding a graphical presentation of the data to the hot topic of the zones pulled this page media-wise.”

The name-and-shame approach

More than that, what Atlas of Hate did was name and shame local governments who are otherwise generally protected from the national or, let alone, the global spotlight, and expose them to the scrutiny of important institutions other than their local constituencies. For Kuba, this was the right strategy:

“All attempts at argumentation were like talking to the wall. Only the vision of losing EU money and the embarrassment of their image appealed to them. If you can’t get by on kindness, the only thing left is constant pressure from many sides.”

Thankfully, it did not backfire.”It did not translate into any stricter laws. On the contrary, Atlas stopped the trend of adopting these resolutions, which then began to be repealed.”

Abolishing “LGBT-free zones”

Various factors contributed to the abolition of “LGBT-free zones.” Across Europe, several towns ended twinning partnerships with their Polish “LGBT-free” counterparts. For example, the Italian city of Alpette was already preparing to enter into a partnership with the Polish city of Poniatowa when it received an open letter from Atlas of Hate co-founders and other campaigners. It ended such a plan soon after.

Local governments also lost millions in critical funding from the European Union (EU) and other countries. The town of Świdnik, 10 kilometers from Lublin, took the biggest hit. In 2021, it lost 40 million Polish zloty (PLN) [US$10.8 million] that it intended to use to create and upgrade town infrastructure after the Norwegian government deemed “LGBT-free” zones to be “fundamentally against the respect for human rights.”

Perhaps the most consequential were the series of actions taken by EU bodies in response to these zones. In 2020, the European Commission sent a letter to five provinces warning that anti-LGBTIQ ideology resolutions can put them in violation of their legal obligations and risk millions in funding.

Activists holding an “LGBTIQ Freedom Zone” banner in front of the EU. © AFP via Getty Images

The European Parliament also passed two resolutions against these “LGBT-free zones,” including one urging the European Commission to use “all tools in its power” to address this threat and declaring the EU an “LGBTIQ Freedom Zone.” One of the steps the European Commission took was enacting a provision prohibiting partnership agreements with local governments with discriminatory policies. Since then, “the pace of repealing these resolutions accelerated significantly.”

The towns strike back

The Atlas of Hate helped keep the pressure on decision-makers to work toward eliminating these resolutions. Their crucial work has not gone unnoticed. In 2020, 43 MEPs nominated the Atlas of Hate co-founders for the European Parliament’s prestigious Sakharov Prize.

However, they were also targeted by the hostile local governments. Seven of the nearly 100 “LGBT-free” towns sued the four activists for defamation, demanding US$64,000 and a public apology before the European Parliament, among others, for putting them on the map. Kuba pointed out that:

“It is worth doing business under a banner, leaving your own faces and names in the background. The factual, informative tone of our communications also helped to calm the atmosphere around advocacy activities, but unfortunately, this has not protected us from legal attacks.”

Today, these malicious lawsuits have either been dropped, dismissed, or are pending appeal. However, some activists still bear the effects of right-wing harassment and intimidation. Bart Staszewski, who led a photo project aiming to show the human impact of anti-LGBTIQ resolutions, “suffered the greatest negative consequences.” Staszewski “was the most visible and active on social media, so unfortunately, he became the target of massive social media attacks coordinated by right-wing politicians…It is on him that the history of the zones has left the greatest psychological mark.”

“Zones” photo project showing queer people in front of the town signs of municipalities that declared themselves to be free of “LGBT ideology.” © Bart Staszewski

A continuing fight

The fight is far from over. On June 1, 2025, Karol Nawrocki, a conservative supported by the Law and Justice Party, won the presidency. He opposes same-sex marriage and said “the LGBT community cannot count on me to address their issues,” leading activists to fear a reinvigoration of the far-right and a return to the “dark times.” Nawrocki, whose views oscillate between the far-right Law and Justice Party and the even more extreme Confederation, is bad news for LGBTIQ people, Kuba warned:

“The coalition government has not stepped down; it is still in power. But it lacks the resolve to restore the rule of law…The president can veto laws, so we can’t count on signing laws on civil unions or the criminalization of hate speech based on sexual orientation and based on gender.”

While the threat of losing access to EU funds makes it less likely, the return of “LGBT-free zones” cannot be ruled out:

“We’re in for two years of stagnation, and then there will probably be another storm around the LGBTQIA community again. A return to the trend of anti-LGBT resolutions cannot be ruled out. The United States has passed several hundred of them, and they are a rich source of inspiration for the far right around the world.”

Kuba and other LGBTIQ activists are not going anywhere. “The Atlas of Hate will remain a collection of documents,” Kuba affirmed. “In the future, I plan to write a book based on it. I have collected a lot of documents related to the zones, and it would be good to summarize it all, preferably in the form of a book.”

Tips for activists

From U.S. states prohibiting gender-affirming care to Indonesian cities fining LGBTIQ people for being a “public nuisance,” anti-LGBTIQ backlash has gone local. Kuba gave us tips that could be useful to activists facing similar circumstances:

- Continuously update your database tracking legal and policy developments, and always search for different ways to obtain information.

- Create a database of activists, media personnel, allied politicians, and other friendly actors, with their social media, email addresses, and other contact details.

- Learn to write messages on three levels: (1) longer, comprehensive, thematically organized, and clear texts, (2) few-sentence elevator pitches, and (3) one-liners or short, neat one-sentence summaries for quoting in headlines.

- Invest in the graphical presentation of your data to attract interest.

- Use various social media channels and the traditional blog for longer texts requiring visual formatting.

- On social media, tag people who might be interested in the topic for some reason, such as where they live, where they come from, or their prior experience. “We focused more on reaching specific people than building the widest possible reach. Socials were an indirect path for us through which we reached out to the mainstream media, politicians, and officials.”

- Closely read and analyze anti-LGBTIQ resolutions in order to take apart their arguments. “Local government officials were unable to answer most of the questions formulated from such an analysis of the resolutions they themselves had passed.”

- View the issue from different angles and look for new ways to influence politicians and local government officials (e.g., requests for information, requests for administrative action, petitions, demonstrations, correspondence with officials, etc.).

- And a very practical tip: consistently use one contractual address and one name in your transactions.

- Golden tip: Count on several years of relentless work. Politicians and local government officials think in a time horizon limited by their term lengths and current political arrangements. Our longer time perspective gives us an advantage.