How the “Si Acepto” campaign changed the narrative in Costa Rica

Beginning in 2006, a number of attempts have been made to press marriage equality forward, both in the legislature and the courts. Ultimately however, it was the Inter-American Court of Human Rights which made the defining decision in January 2018. The court ruled that countries that are signatories to the American Convention on Human Rights were required to allow same-sex couples to marry. Inter-American Court of Human Rights rulings are fully binding on member countries and take precedence over local laws.

On August 8, 2018, the Costa Rica Supreme Court declared the sections of the Family Code prohibiting same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional, and gave the Legislative Assembly 18 months to reform the law accordingly,meaning that same-sex marriage will become legal on May 26, 2020, at the latest.

The ruling caused uproar in the country and is widely regarded as one of the causes behind the divisive 2018 Costa Rican general election. The liberal Carlos Alvarado Quesada won the election and committed the government to moving forward on same-sex marriage recognition.

While celebrating this victory, the LGBT movement recognized that there was work to be done to win over popular opinion that remained firmly opposed. This interview with Gia Miranda, member of Familias Homoparentales y Diversas de Costa Rica (Homoparental and Diverse Families of Costa Rica), who is part of the Movement for Civil Marriage Equality – MCME, explores how the movement in Costa Rica is responding to this challenge through a coalition campaign called “Si Acepto”.

© ticotimes.net

Gia, what kind of context are you working in?

During the electoral process of 2018, Marriage Equality became the divisive issue of the day. Conservative candidate Fabricio Alvarado, who won the first round and lost the runoff, placed the rejection of homosexuality in general, and equal marriage in particular, at the center of his messaging. The wave of electoral violence it triggered was one of the reasons why the MCME was founded and the campaign launched. We wanted to eliminate some of the harsher reactions to the impending coming into force of equal marriage.

The Evangelical community in Costa Rica was a specific concern to us. It makes up 25% of the population, according to Latinobarometro, a regional poll. And the weight of this conservative political constituency has a strong impact on legislative and electoral processes.

Please tell us about how the Movement for Civil Marriage Equality works.

The Movement for Civil Marriage Equality (MCME) is composed of 36 collectives and social organizations that joined the initiative.

It is led by two of us – from different organizations. We both have a background in marketing, so we are comfortable and have experience doing campaigns.

The two of us proposed the Si Acepto campaign at the beginning of 2018, after we participated in a workshop with Freedom to Marry, the campaign that led the efforts to win equal marriage in the US and now advises other countries in similar processes.

As we gathered the movement’s members and proposed to conduct a campaign, most voted in favor, with the exception of one organization that had some reservations on the need to elevate the issue unnecessarily at the time.

We made a call to those interested in taking part in the process of the campaign more directly, and the two or three more frequent participants joined the “Campaign Central Committee” (CCC), the group in charge of most decision-making processes. The CCC led fundraising efforts, outreach, and administrative support – the latter in partnership with the “Diverse Families” organization, which provided the legal backdrop.

Before each big decision, we informed the rest of the movement through chat. We always maintained close communications and guaranteed the confidentiality of the process and the use of information.

As part of this process, we created a cooperative model of social outreach, which brings together civil society, the private sector, the government, and some international organizations. We believe that a country that is inclusive and respectful of differences benefits all sectors of society and the economy, and that union is the key to success.

What exactly was the objective of the campaign?

Our goal was to diminish the effect of the possible barriers and resistances to the coming into force of civil equal marriage in Costa Rica, through the development of a narrative based on human histories and common values, that more easily connect to the population’s hearts.

Did you conduct any formal research on your target group? What are the most interesting elements from this research?

“No teníamos ni un cinco”! (We didn’t have a penny) and had to begin with something, so our initial research consisted of a poll on our social media, which we shared as extensively as possible.

Shortly after, we requested support from Garnier BBDO, one of the biggest marketing and publicity agencies in the country. They agreed and have since then (Dec 2018) offered pro bono support.

With their help, we conducted in-depth research and focus groups, through which we were able to understand that the campaign had to go beyond the LGBTIQ community and its allies. But also that the anti-rights groups were beyond our reach: These are people that just won’t accept this situation, “even if Jesus himself came down and told them to stop doubting”.

What were the essential frames and messages that you used? Why did you choose these?

We determined that some of the key common values for Costa Ricans are respect, justice and family. These are equally important to Catholics and Evangelicals, so we tried to build our narratives to show how the acceptance of civil equal marriage promotes the values that most people already share.

For example, in one story, a father demonstrated this by showing how he learned to respect his lesbian daughter, her life project, and relationship, even despite his traditional upbringing. “I was concerned about what people who knew me would say, but what was truly drowning me was machismo”, he says in his testimony, “Showing emotions is good because you get rid of myths and prejudices. And I feel more of a man for having recognized my mistakes. Now my daughter can come home, can get married and make her own family, just like my wife and I did.”

There are some variations on the narrative pointing to how traditionally masculine environments can also favor acceptance and solidarity, as in the case of a rugby player who comes out of the closet, to gradually gain the support of his initially reluctant fellow players. He did this by showing that the values he enacted were the ones everyone shared: discipline, respect, humility, passion, and solidarity.

The narrative also emphasized the role of family and mutual support. The case of one family, for example, points to the reluctance of the father, a former evangelical pastor, to accept his gay son, but he overcomes this when he witnesses the unfaltering support for the son from the rest of his family.

Other testimonials share different angles to the same acceptance narrative, for example, by featuring a long-time policeman, a feminist leader, and the community of Quepós coming out in support of the community’s renowned barber.

How did you decide on the campaign tactic?

We didn’t focus on people that were already on our side, or our complete detractors. We were seeking to talk to those that perhaps feel that the issue doesn’t affect them or who don’t know how to talk about it, people who will fear what others might think if they express support for marriage equality. We believe this moveable middle accounts for 2/5 of the population of Costa Rica.

The first part of the strategy was clearly defining the dos and don’ts amongst ourselves. We agreed that the campaign was not necessarily going to be marked by “traditional” activism. We were not going to use rainbow flags, and for strategic reasons, would only touch upon the issue of civil marriage. We wouldn’t go to other, equally important LGBTIQ issues, such as trans rights, diverse families, adoption, among others, because people understand one topic at a time more easily.

The campaign would also center on real stories and real people to induce empathy.

A key decision was to emphasize the word “civil” to differentiate civil marriage – which is our only focus – from religious marriage, which is what most people immediately think of in Costa Rica. A survey we conducted showed that there was a 20 percent increase in people’s acceptance towards allowing same-sex couples to marry when we specifically made clear that we meant marriage officiated by a lawyer and not by a priest.

How was the campaign disseminated?

We dreamed big. We didn’t want a digital campaign only. We wanted television, radio, digital, and other forms of communication.

The government supported the campaign with an important donation in airtime on the official TV channel, and while private channels don’t give anything for free, we secured extremely good deals.

We also allocated some funds to radio and billboards. Billboard companies donated four spaces in key traffic areas, with access to provinces outside of the capital city.

The print media picked it up without us needing to do much promotion.

We also discovered that Whatsapp is a very effective tool to generate conversations about the issue. We prepared materials anticipating our releases, prompting allies to share videos and other materials; and this resulted into a myriad of one-on-one or group conversations.

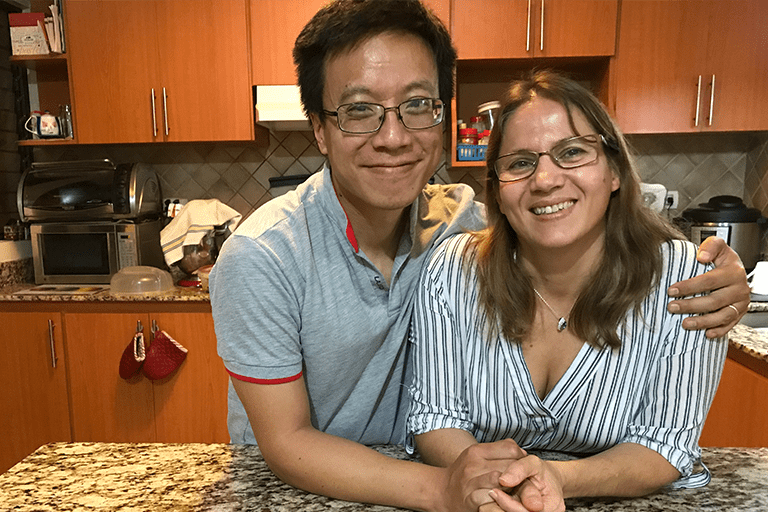

© siaceptocr.com

What do you think have been your major impacts or successes?

Success can be measured by our media outreach throughout the country with a budget that, for marketing purposes, was truly minimal. Through paid advertising alone, we reached around 1.5 million people (in a country of 5 million people).

We don’t have the tools to measure the reactions to the TV ads, but we witnessed improvements in the public conversation, and we are convinced that we are having a strong impact at the social level.

What were the challenges related to funding, and how did you overcome them?

We had very limited time to fundraise, because we started in February 2019 and wanted to launch in July, so we made a quick shortlist of companies which had LGBT inclusion programs and could be interested in participating.

We sent around 60 formal introduction letters, with support from the Presidential Commissioner for LGBTIQ Issues, and convened a gathering of those who responded. Only four companies from this initial group eventually donated, not a lot as you can see, but you start with something and try to find different strategies. It’s important not to use a single formula.

What advice would you give people thinking about doing this work?

You need to have an objective that is very clearly defined. When success starts kicking in, it’s important not to let the egos interfere, to understand that you are doing a public service to the community, and that you need to give all you possibly can to the cause.

Any last words of advice or encouragement to other activists?

“Go for it. Don’t let it bug you when things don’t come out perfectly”.

© siaceptocr.com