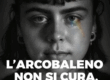

“LGBT people and the rainbow flag are becoming a new symbol of the fight for freedom and democracy.“ -Campaign against Homophobia, Poland (KPH).

Over the past two years, the re-election strategy of the Polish right-wing has focused on whipping up moral panic against sexual and gender diversity, spreading misinformation and vague statements, such as right-wing candidate Andrzej Duda declaring that LGBT ideology was “as dangerous as communism”.

Within this movement, several Polish cities declared themselves “LGBT-free zones.” In early August 2020, the Minister of Justice announced the introduction of a draconian law that obliges non-governmental organizations to disclose any funds they receive from outside Poland. This echoes frighteningly similar laws passed in Russia and Hungary aimed at narrowing civic spaces.

After Duda’s election, the opposition immediately mobilised to denounce his aggressive homo/transphobia. On the very swearing-in ceremony, MPs from the opposition wore rainbow colours, and rainbow face-masks, to protest against rising anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric.`

And after that, something happened that would spark the fire.

On August 7, 2020, a Polish court issued an outrageous order for the two-month pre-trial detention of Margot, an activist for the queer “Stop Nonsense” [Stop Bzdurom] collective. Margot had been arrested on charges of attacking a van that was promoting anti-LGBTQI+ propaganda and blaring offensive claims from loudspeakers.

Stop Nonsense had already gained notoriety for covering monuments in Warsaw with rainbow flags. This attracted outrage from conservatives, especially when the Monument of Christ was included in its targets.

A representative for KPH, the national Campaign against Homophobia, said, “Margot did what most of us wanted but were afraid to do. The State and the authorities no longer protect us, so she started to defend herself.”

Hundreds of demonstrators gathered outside the Warsaw offices of the “Campaign against Homophobia” to protest against the order to arrest Margot. Police soon stormed the rally, using “excessive force” according to many observers. About fifty people were arrested. And that was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

These arrests prompted outrage from opposition politicians and human rights groups. Although Poland was experiencing a rise in cases of COVID-19, at least 15 solidarity protests, both big and small, were organised in towns and cities across Poland, as well as in Budapest, London, New York, Paris, and Berlin.

Symbolically, activists and citizens hung rainbow flags on monuments during the protest.

Police slowly released LGBTQI+ activists from custody, but not Margot. In the days that followed, protests continued in almost all major cities across Poland.

After weeks of protests and action, Margot was finally released on August 28, 2020.

Polish LGBTQI+ activists have likened these protests to the Stonewall riots in New York in 1969.

The situation in Poland is characterized by an increase in State-sanctioned hatred, discrimination, and repression. Meanwhile, the sexual and gender minorities movement is becoming increasingly well organised and gaining support from broader constituencies.

In May this year, ILGA Europe ranked Poland as the worst country in the EU for LGBTQ rights, with attacks from the government and the church being particularly responsible for increasing discrimination.

However, Adam Bodnar, the Polish Human Rights Commissioner, commented that “Polish authorities didn’t predict that putting Margot in detention would cause such powerful protests from the LGBTQ community and that those protests would be supported by opposition politicians and pro bono lawyers.”

As in several other countries, the treatment of LGBTQI+ people in Poland acts as an indicator of the status of its democracy and respect for civic freedoms.

Like canaries in a coalmine, LGBTQI+ are the visible “tip of the iceberg” for Human Rights violations by repressive regimes.

This might make LGBTQI+ movements beacons of freedom and democracy, whether they meant for it to happen or not. It seems like that moment has arrived for Poland.

Questions for campaigners

Beyond the specificities linked to the Polish context, these events give rise to some critical questions for campaigners:

Movement coherence/discipline

As much as diversity within any social movement is needed and welcome, there are also challenges when many diverse voices and different tactics are involved.

In this case, “Stop Nonsense” took a provocative stance by “rainbowing” the Monument of Christ. Had it been discussed with the broader movement? Whatever the pros and cons, this action was bound to unleash responses impacting the movement and its supporters.

It makes sense for activists taking part in more radical action to announce what will happen to the rest of the players in the field so they can take the necessary steps to mitigate any backlash.

In addition, more transparency within the movement can better integrate strategies rather than disperse energies on several fronts. Successful campaigns have invested a lot in sharing their strategy with other stakeholders, which has resulted in many benefits:

- Dissent due to a simple misunderstanding can be avoided. For example, when a campaign shared their social research on public attitudes and how to influence them, choices in terms of messaging and target groups became clearer to all and were not disputed.

- Other parts of the movement adapted their own strategies to feed into the broader movement. Successful campaigns have leveraged each other’s strengths to achieve a common goal, even when that meant playing Good Cop -Bad Cop.

- Other parts of the movement were better able to make their own voices heard. Some campaigns started with a narrow “LG” focus and sharing their strategies led to a better integration of trans, queer, intersex, non-binary and other people.

- Key supporters from outside the movement, like the Polish MPs, were better able to adjust their messaging to the strategies.

Obviously, not every action can be discussed and agreed upon. Sometimes, or rather, most of the time, there are dissenting voices and opposing tactics within the movement. Some level of strategic dialogue should nevertheless be maintained, but this raises important questions:

Is it the core responsibility of campaigners to (confidentially) share their strategic plans with others? What if sharing strategic plans might result in them being thwarted? Are there any more benefits than the ones listed above? What, on the other hand, are the challenges?

Engagement/Sanction

Campaigners often face a hard choice when calling for support from institutional allies, especially outside the country: should they call for sanctions? Should they invite allies to disengage with the authors of discrimination or violence?

In Poland, the LGBTQI+ movement encouraged allies to reinforce their presence on the political scene rather than move away. This was particularly important in the case of the twin towns of Polish cities that had declared themselves to be “LGBT-free zones.”

"Wir wollen zeigen, dass wir existieren." Deutsche und Polen haben in #Slubice und #Frankfurt (Oder) gemeinsam gegen sogenannte "#LGBT-freie Zonen" demonstriert. #slubiceffopride #lgbtq #lgbtiq pic.twitter.com/sPrNjHUV3q

— rbb|24 (@rbb24) September 5, 2020

As an example, on September 5, a symbolic cross-border march took place between the neighbouring cities of Slubice, Poland, and Frankfurt an der Oder, Germany, to protest against the notion of “LGBT-free zones.”

Institutional isolation leaves activists even more separated, bringing them closer to authorities. But if the allies’ engagement is too meek, it equals support for the oppressors.

A delicate balance to strike, and surely a lot of diverse experiences around the globe on this issue.